Foods High in Copper: A Nutritional Guide

Direct answer: Copper is an essential mineral vital for iron metabolism and red blood cell formation. A deficiency can lead to a specific type of anemia, even with adequate iron intake, because your body needs copper to properly access and use stored iron. The best dietary sources include beef liver, oysters, cashews, and dark chocolate.

TL;DR Copper is a crucial trace mineral that plays a key role in energy production, nervous system function, and connective tissue health. Its most important function regarding anemia is its role in iron metabolism. Without enough copper, your body cannot properly absorb and use iron, which can lead to a condition called iron-refractory anemia, where anemia persists despite sufficient iron intake. Most people get enough copper from a balanced diet, but certain conditions or high zinc intake can interfere with its absorption.

- Beef Liver: The most concentrated source, providing several times the daily requirement in one serving.

- Oysters: Shellfish, particularly oysters, are exceptionally rich in copper.

- Nuts and Seeds: Cashews, sesame seeds, and sunflower seeds are excellent plant-based sources.

- Legumes: Lentils, chickpeas, and soybeans offer a good amount of copper.

- Dark Chocolate: A tasty source; the higher the cocoa content, the more copper it contains.

- Mushrooms: Shiitake mushrooms are a notable vegetable source of this mineral.

- Whole Grains: Quinoa, oats, and barley contribute to daily copper intake.

Want the full explanation? Keep reading ↓

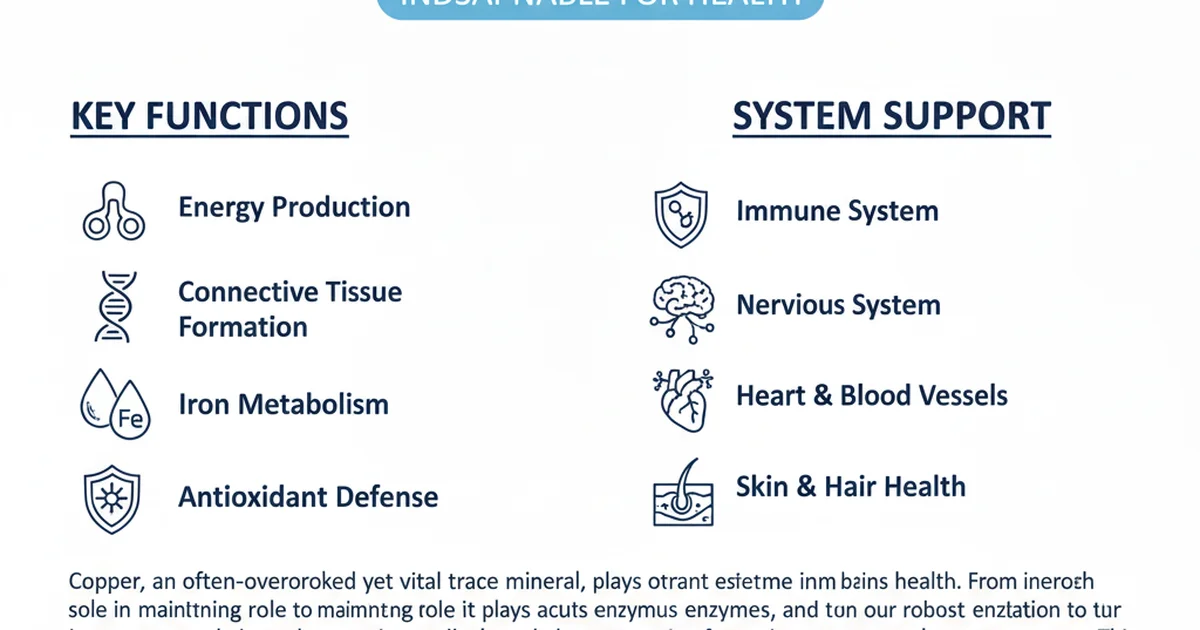

Copper, an often-overlooked yet vital trace mineral, plays an indispensable role in maintaining optimal human health. From the intricate processes of energy production within our cells to the robust functioning of our immune and nervous systems, copper is a fundamental component of numerous enzymes and metabolic pathways. While present in relatively small amounts in the body, its impact is profound, influencing everything from iron metabolism and connective tissue formation to antioxidant defense.

This comprehensive guide delves into the world of copper, exploring its essential functions, identifying key dietary sources, understanding the factors that influence its absorption and utilization, and discussing the nuances of supplementation. For most individuals, a balanced diet provides sufficient copper, but understanding its role and sources is crucial for preventing imbalances that can lead to significant health issues.

The Essential Role of Copper in the Body

Copper is a cofactor for several critical enzymes, known as cuproenzymes, which are involved in a wide array of physiological processes. Its unique ability to cycle between two oxidation states (Cu+ and Cu2+) allows it to participate in electron transfer reactions, making it central to many biochemical functions.

- Energy Production: Copper is a crucial component of cytochrome c oxidase, the terminal enzyme in the electron transport chain, which is vital for cellular respiration and the production of ATP, the body's primary energy currency. Without adequate copper, cells cannot efficiently generate energy.

- Iron Metabolism: Copper is inextricably linked to iron metabolism. The cuproenzyme ceruloplasmin acts as a ferroxidase, converting ferrous iron (Fe2+) to ferric iron (Fe3+), which is necessary for iron loading onto transferrin, the primary iron transport protein in the blood. A deficiency in copper can therefore lead to iron-refractory anemia, even if iron intake is sufficient.

- Connective Tissue Formation: Copper is essential for the function of lysyl oxidase, an enzyme that cross-links collagen and elastin. These proteins are fundamental for the structural integrity of bones, cartilage, skin, blood vessels, and other connective tissues.

- Neurotransmitter Synthesis: Several neurotransmitters, including dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine, require copper-dependent enzymes for their synthesis. Copper plays a role in the function of dopamine beta-hydroxylase, critical for nervous system health.

- Antioxidant Defense: Copper is a component of superoxide dismutase (SOD1), a powerful antioxidant enzyme that protects cells from damage by neutralizing harmful free radicals. This role underscores copper's importance in mitigating oxidative stress.

- Immune Function: Copper contributes to the development and maintenance of a healthy immune system, influencing the proliferation and maturation of immune cells.

- Melanin Production: The enzyme tyrosinase, which is involved in the synthesis of melanin (the pigment responsible for skin, hair, and eye color), is copper-dependent.

Dietary Sources of Copper

Most people can meet their daily copper requirements through a varied and balanced diet. Copper is widely distributed in both plant and animal foods, making deficiency due to insufficient dietary intake relatively uncommon in developed countries. Here are some of the richest sources:

- Organ Meats: These are by far the most concentrated sources of copper.

- Beef Liver: A single serving (3 ounces) can provide several times the recommended daily allowance (RDA).

- Other animal livers (lamb, pork, chicken) are also excellent sources.

- Seafood: Many types of shellfish and some fish are rich in copper.

- Oysters: Exceptionally high in copper, often providing significant amounts in a small serving.

- Crab, lobster, mussels, and squid are also good sources.

- Certain fish like salmon and tuna contain moderate amounts.

- Nuts and Seeds: These are convenient and healthy sources of copper.

- Cashews: One of the best nut sources.

- Almonds, sesame seeds, sunflower seeds, chia seeds, and flaxseeds are also good.

- Legumes: A staple in many diets, legumes offer a good amount of copper.

- Lentils, chickpeas, kidney beans, black beans, and soybeans.

- Whole Grains: Opting for whole grains over refined grains can boost copper intake.

- Oats, quinoa, barley, and whole wheat products.

- Dark Chocolate: A delicious source, the higher the cocoa content, the more copper it contains.

- Fruits and Vegetables: While generally lower than other categories, some produce can contribute significantly, especially when consumed regularly.

- Mushrooms (especially shiitake), potatoes, avocado, leafy greens (spinach, kale), and dried fruits like prunes and figs.

It's important to note that the copper content in foods can vary based on soil composition, processing methods, and cooking techniques. Cooking in copper cookware can also impart small amounts of copper into food, though this is generally not a primary source of dietary copper.

Bioavailability of Dietary Copper

Bioavailability refers to the proportion of a nutrient that is absorbed from the diet and utilized by the body. For copper, several factors can influence its bioavailability:

Factors Enhancing Copper Absorption:

- Amino Acids: Certain amino acids, particularly histidine and methionine, can form chelates with copper, facilitating its absorption.

- Citric Acid: Found in citrus fruits, citric acid can also enhance copper absorption.

- Low Copper Status: The body's absorption efficiency increases when copper stores are low, a natural regulatory mechanism.

Factors Inhibiting Copper Absorption:

- Zinc: This is perhaps the most significant antagonist of copper absorption. High intakes of zinc, often from supplements, can induce copper deficiency. Zinc and copper compete for the same absorption pathways in the intestines, and zinc stimulates the production of metallothionein, a protein that binds copper and prevents its transfer into the bloodstream. This is a crucial consideration for anyone taking high-dose zinc supplements.

- Iron: Very high doses of iron supplements can interfere with copper absorption, though this interaction is less pronounced than with zinc.

- Molybdenum: Molybdenum can complex with copper, forming insoluble compounds that reduce copper absorption and increase its excretion, primarily in ruminant animals, but also to some extent in humans.

- High Doses of Vitamin C: While vitamin C is generally beneficial, extremely high doses (e.g., >1500 mg/day) have been shown in some studies to potentially interfere with copper bioavailability by reducing cupric (Cu2+) to cuprous (Cu+) form, which is less readily absorbed. However, this is not a concern with typical dietary vitamin C intake.

- Phytates and Fiber: Found in whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds, phytates can bind to copper and other minerals, forming insoluble complexes that reduce absorption. However, the overall nutritional benefits of these foods typically outweigh this minor inhibitory effect, and fermentation or soaking can reduce phytate content.

Individual factors like age, genetic predispositions (e.g., mutations affecting copper transport proteins), and the presence of gastrointestinal disorders (e.g., celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, or bariatric surgery) can also significantly impact copper absorption and metabolism.

Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) for Copper

The recommended daily allowance (RDA) for copper is set to meet the needs of most healthy individuals.

- Adults (19+ years): 900 micrograms (mcg) per day.

- Pregnant Women: 1,000 mcg per day.

- Lactating Women: 1,300 mcg per day.

- Children: RDAs vary by age, ranging from 200 mcg for infants to 890 mcg for adolescents.

The Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for adults is 10,000 mcg (10 mg) per day. Consuming copper above this level regularly can lead to adverse health effects.

Copper Deficiency and Its Implications

While rare in healthy individuals consuming a balanced diet, copper deficiency can occur due to various factors, including prolonged inadequate intake, malabsorption issues, or excessive intake of antagonistic nutrients like zinc.

Symptoms of copper deficiency are diverse and can mimic other conditions, making diagnosis challenging. They often reflect copper's multiple roles in the body:

- Anemia: A common sign, often microcytic and hypochromic, resembling iron deficiency anemia but unresponsive to iron supplementation alone. This is due to copper's role in iron metabolism via ceruloplasmin.

- Neutropenia: A reduction in neutrophils, a type of white blood cell, leading to increased susceptibility to infections. This is a hallmark hematological sign.

- Neurological Symptoms: Copper is crucial for nervous system health. Deficiency can lead to a range of neurological issues, including myelopathy (damage to the spinal cord), peripheral neuropathy (nerve damage in the extremities), and ataxia (loss of coordination). These can manifest as difficulty walking, numbness, tingling, and weakness. For a deeper understanding of these specific neurological impacts, refer to our article on [copper deficiency neurological symptoms explained].

- Osteoporosis and Bone Abnormalities: Due to copper's role in collagen cross-linking, deficiency can impair bone strength and development.

- Hypopigmentation: Lighter hair or skin color can occur due to impaired melanin production.

- Impaired Immune Function: Increased susceptibility to infections.

- Cardiovascular Issues: Abnormalities in blood vessel integrity.

Diagnosis of copper deficiency typically involves blood tests, including serum copper and ceruloplasmin levels. In some cases, genetic testing may be warranted, particularly for inherited conditions like Menkes disease. For more information on diagnostic approaches, including the role of testing in identifying deficiencies, see [serum copper test Wilson's disease and deficiency].

Copper Toxicity (Excess Copper)

While deficiency is rare, copper toxicity is also a concern, particularly with unsupervised supplementation or certain genetic conditions.

- Acute Toxicity: Usually results from accidental ingestion of large amounts of copper salts (e.g., from supplements, contaminated water, or acidic foods stored in unlined copper containers). Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and in severe cases, liver damage, kidney failure, and hemolytic anemia.

- Chronic Toxicity: Can develop from prolonged high intake or, more commonly, from genetic disorders that impair copper excretion. The most well-known genetic disorder is Wilson's disease, an inherited condition where the body cannot properly excrete excess copper, leading to its accumulation in the liver, brain, eyes, and other organs. This can result in severe liver disease, neurological dysfunction (tremors, speech difficulties, dystonia), and psychiatric problems. For comprehensive details on Wilson's disease and its diagnosis, consult our article on [serum copper test Wilson's disease and deficiency].

Monitoring copper levels is crucial when toxicity is suspected. Understanding the [copper normal range and test result meaning] is essential for accurate diagnosis and management.

Copper Supplementation

Copper supplementation should generally only be undertaken under medical supervision, especially given the narrow therapeutic window between deficiency and toxicity, and its complex interaction with other minerals like zinc.

- When is it necessary? Supplementation is typically recommended only when a medical professional has diagnosed a copper deficiency based on symptoms and laboratory tests. This might be due to malabsorption conditions, bariatric surgery, certain medications, or long-term high-dose zinc supplementation.

- Forms of Supplements: Copper is available in various forms, including cupric oxide, cupric sulfate, copper gluconate, and copper chelate (e.g., copper bisglycinate). The bioavailability can vary between forms, with chelates often considered more bioavailable.

- Caution: Self-supplementing with copper is strongly discouraged. Excessive copper intake can lead to toxicity, cause or worsen zinc deficiency, and potentially interact with other medications. Always consult a healthcare provider before starting any copper supplement.

Monitoring Copper Levels

Assessing copper status typically involves blood tests. These help diagnose deficiency, toxicity, and monitor treatment effectiveness.

- Serum Copper: Measures the total copper circulating in the blood.

- Ceruloplasmin: A copper-containing protein that carries most of the copper in the blood. It's often a more reliable indicator of copper status than serum copper alone, as ceruloplasmin levels can be affected by inflammation or other conditions.

- 24-Hour Urine Copper: Used to assess copper excretion, particularly in cases of suspected Wilson's disease.

- Liver Biopsy: In some cases, a liver biopsy may be performed to measure copper content directly, especially for diagnosing Wilson's disease.

Understanding the results of these tests requires professional interpretation.

| Population | Normal Range | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Men | 70-140 | mcg/dL | Varies by lab |

| Adult Women | 80-155 | mcg/dL | Higher during pregnancy/OC use |

| Children (1-10 yrs) | 70-140 | mcg/dL | Age-dependent |

| Infants (<1 yr) | 20-70 | mcg/dL | Increases with age |

Important Note: These ranges are general guidelines. Actual normal ranges can vary slightly between different laboratories. Always interpret your test results in consultation with your healthcare provider.

Conclusion

Copper is an indispensable trace mineral crucial for a myriad of bodily functions, from energy production and iron metabolism to nerve and immune system health. A balanced diet rich in diverse whole foods, particularly organ meats, seafood, nuts, seeds, and legumes, typically provides adequate copper for most individuals. Understanding the factors that influence copper bioavailability, especially the antagonistic relationship with zinc, is vital for maintaining optimal levels.

While deficiency is rare but can be serious, toxicity is also a concern, particularly with genetic predispositions like Wilson's disease or inappropriate supplementation. Therefore, any concerns regarding copper status, whether deficiency or excess, warrant a discussion with a healthcare professional. They can provide accurate diagnosis through appropriate testing and guide safe and effective management strategies, ensuring this vital mineral continues to support your health without causing harm.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of abnormal Copper levels?

The most common cause of abnormal copper levels varies depending on whether it's a deficiency or an excess. For copper deficiency, while rare from diet alone in developed countries, a significant cause is excessive zinc supplementation, which directly interferes with copper absorption. Other causes include malabsorption conditions (e.g., celiac disease, gastric bypass surgery) or rare genetic disorders like Menkes disease. For copper excess (toxicity), the most common cause is the genetic disorder Wilson's disease, where the body cannot excrete copper properly, leading to accumulation in organs. Acute toxicity can also result from accidental ingestion of large amounts of copper from supplements or contaminated sources.

How often should I get my Copper tested?

Copper levels are generally not recommended for routine testing in healthy individuals. You should only get your copper levels tested if you exhibit symptoms suggestive of a deficiency (e.g., unexplained anemia, neurological issues, frequent infections) or toxicity (e.g., unexplained liver problems, neurological symptoms, psychiatric changes). Testing may also be recommended if you have risk factors such as long-term high-dose zinc supplementation, a history of bariatric surgery, certain gastrointestinal disorders, or a family history of genetic copper metabolism disorders like Wilson's or Menkes disease. Always consult your healthcare provider to determine if testing is appropriate for your situation.

Can lifestyle changes improve my Copper levels?

Yes, lifestyle changes, primarily dietary modifications, can significantly improve your copper levels if they are imbalanced.

- For Deficiency: Focus on incorporating copper-rich foods into your diet, such as organ meats (liver), seafood (oysters, crab), nuts (cashews, almonds), seeds, legumes, whole grains, and dark chocolate. If you are taking high-dose zinc supplements, discuss with your doctor whether reducing the zinc dose or supplementing with copper (under medical guidance) is appropriate, as excessive zinc is a common cause of induced copper deficiency.

- For Toxicity: If you have elevated copper levels, especially due to Wilson's disease, lifestyle changes alone are insufficient, and medical treatment is paramount. However, your doctor may advise you to avoid high-copper foods and copper-containing supplements. Avoiding acidic foods stored in unlined copper cookware is also a prudent measure to prevent accidental copper leaching. For all cases of abnormal copper levels, professional medical advice is essential for safe and effective management.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Always consult a healthcare professional.