Copper Normal Range and Test Result Meaning

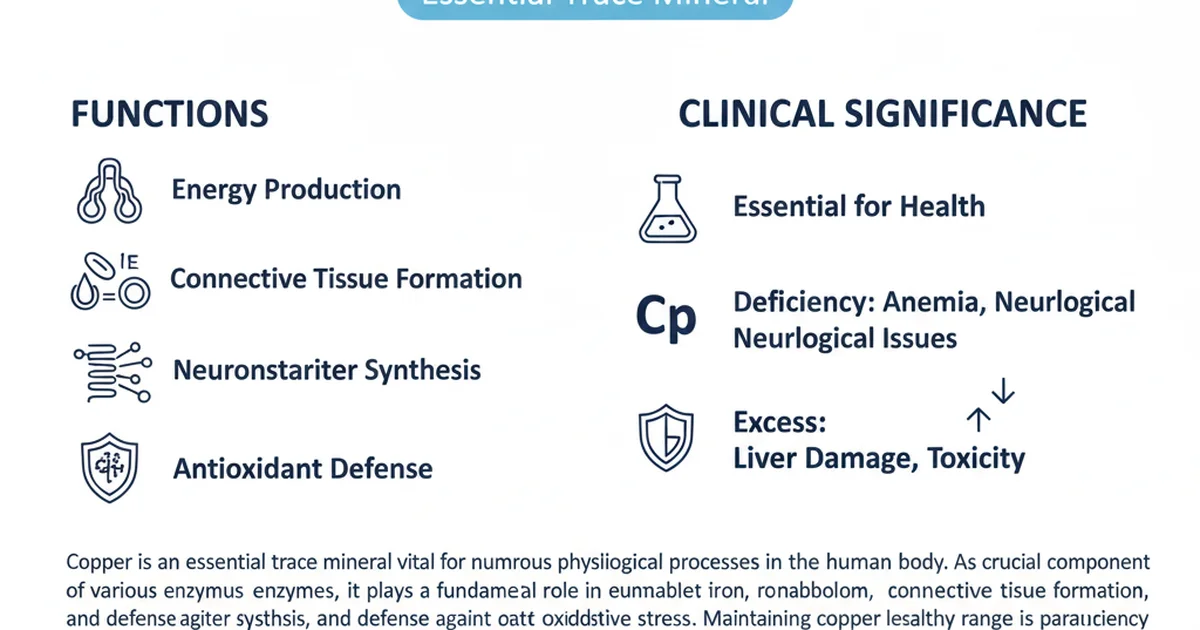

Copper is an essential trace mineral vital for numerous physiological processes in the human body. As a crucial component of various enzymes, it plays a fundamental role in energy production, iron metabolism, connective tissue formation, neurotransmitter synthesis, and defense against oxidative stress. Maintaining copper levels within a healthy range is paramount for overall health, as both deficiency and excess can lead to significant health complications.

Understanding your copper test results requires not only knowing the normal reference ranges but also appreciating the context of your health status, dietary habits, and any medications or supplements you may be taking. This article delves into the significance of copper, its dietary sources, bioavailability, and the implications of its levels in your body.

Understanding Copper Levels: The Basics

Copper is primarily transported in the blood bound to a protein called ceruloplasmin. A small fraction, known as "free copper," is not bound and is biologically active, though its levels are typically very low. Testing for copper levels usually involves measuring total serum or plasma copper, and sometimes ceruloplasmin, or even urinary copper excretion, depending on the clinical suspicion.

Why is Copper Testing Done?

Copper testing is performed for several key reasons:

- Investigating suspected deficiency: Symptoms like unexplained anemia, neurological issues, or bone abnormalities can prompt testing.

- Investigating suspected toxicity: Symptoms such as liver dysfunction, neurological problems, or psychiatric disturbances might necessitate testing for copper excess, particularly in conditions like Wilson's disease.

- Monitoring treatment: For individuals undergoing treatment for copper deficiency or overload, regular testing helps assess the effectiveness of interventions.

- Nutritional assessment: To evaluate overall nutritional status, especially in cases of malabsorption or specific dietary patterns.

Types of Copper Tests

While this article focuses on the general "normal range," it's important to know that various tests assess copper status:

- Serum/Plasma Copper: Measures the total amount of copper in the blood, both bound to ceruloplasmin and free. This is the most common initial test.

- Ceruloplasmin: This protein carries about 90-95% of the copper in the blood. Measuring ceruloplasmin levels can indirectly indicate copper status and is particularly important in diagnosing certain genetic disorders.

- Free Copper: Calculated from total serum copper and ceruloplasmin, this represents the metabolically active copper.

- 24-hour Urine Copper: Measures the amount of copper excreted in urine over a full day. Elevated levels can indicate an inability to properly store copper, as seen in genetic disorders.

- Liver Biopsy: Considered the gold standard for diagnosing copper overload, especially in Wilson's disease, as it directly measures copper accumulation in the liver.

For a more in-depth discussion on specific tests, especially in the context of genetic disorders and deficiency, you can refer to our article on [serum copper test, Wilson's disease, and deficiency].

Copper Normal Range Table

It is critical to understand that laboratory reference ranges for copper can vary significantly based on the analytical method used, the specific laboratory, and the population demographics. The units of measurement can also differ (e.g., µg/dL, µmol/L, ng/mL). Always refer to the specific reference range provided by the laboratory that performed your test. The table below provides illustrative ranges in ng/mL, as specified, but these are general examples and may not reflect your lab's exact values.

| Population | Normal Range | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Men | 30-400 | ng/mL | Varies by lab; consider µg/dL or µmol/L for typical serum copper |

| Adult Women | 15-150 | ng/mL | Lower in premenopausal; often higher in pregnancy due to estrogen |

| Children | 7-140 | ng/mL | Age-dependent; generally higher in infants, lower in young children |

| Pregnant Women | 150-300 | ng/mL | Significantly elevated due to hormonal changes |

Note: The ranges provided in this table are illustrative examples in ng/mL, as per specific instructions. For most clinical serum copper tests, units are typically µg/dL (micrograms per deciliter) or µmol/L (micromoles per liter), with adult normal ranges often falling between 70-140 µg/dL. Always consult your laboratory report for the specific reference range applicable to your results.

Interpreting Test Results

Understanding whether your copper levels are high, low, or within the normal range is crucial for guiding appropriate medical intervention.

High Copper Levels (Hypercupremia)

Elevated copper levels, or hypercupremia, can be a serious concern. While some temporary increases can occur due to acute inflammation or infection, persistently high levels warrant thorough investigation.

Causes of High Copper Levels:

- Acute and Chronic Inflammation: Copper is an acute-phase reactant, meaning its levels can rise during inflammation, infections, or stress.

- Liver Diseases: Conditions like cirrhosis, hepatitis, or cholestasis can impair the liver's ability to excrete copper, leading to its accumulation.

- Estrogen Effects: Estrogen can increase ceruloplasmin synthesis, thereby raising total serum copper levels. This is why women on oral contraceptives or who are pregnant often have higher copper levels.

- Wilson's Disease: This is a rare, genetic disorder where the body cannot effectively excrete excess copper, leading to its accumulation in the liver, brain, eyes, and other organs. While total serum copper might appear low or normal in some cases (due to low ceruloplasmin), free copper levels are typically elevated. This condition requires specific diagnostic approaches, which are detailed further in our article on [serum copper test, Wilson's disease, and deficiency].

- Copper Toxicity: Can result from excessive copper supplementation, exposure to copper-contaminated water, or industrial exposure.

Symptoms of High Copper Levels:

Symptoms can vary widely depending on the severity and duration of the elevation, and the organs affected. They can include:

- Gastrointestinal issues: Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea.

- Liver dysfunction: Jaundice, fatigue, dark urine, liver damage, or even failure.

- Neurological symptoms: Tremors, difficulty walking, speech problems, cognitive impairment.

- Psychiatric symptoms: Depression, anxiety, mood swings, psychosis.

- Kidney problems: Renal dysfunction.

- Hemolytic anemia: Destruction of red blood cells.

Potential Dangers of High Copper Levels:

Chronic copper overload can lead to severe organ damage, particularly to the liver and brain. If left untreated, conditions like Wilson's disease are fatal. Even non-genetic causes of high copper can result in significant health issues and require medical intervention to reduce copper levels and address the underlying cause.

Low Copper Levels (Hypocupremia)

Copper deficiency, or hypocupremia, is less common than other mineral deficiencies but can have serious health consequences.

Causes of Low Copper Levels:

- Malnutrition/Inadequate Dietary Intake: While rare in developed countries, severe malnutrition can lead to copper deficiency.

- Malabsorption Syndromes: Conditions like celiac disease, Crohn's disease, or chronic diarrhea can impair nutrient absorption, including copper.

- Bariatric Surgery: Gastric bypass or other weight-loss surgeries can alter nutrient absorption pathways.

- Excessive Zinc Intake: Zinc and copper compete for absorption in the gut. High doses of zinc supplements (often found in cold remedies or prostate health supplements) can induce copper deficiency. This is one of the most common causes of acquired copper deficiency.

- Menkes Disease: A rare, genetic disorder of copper transport, leading to severe copper deficiency despite adequate intake.

- Chronic Kidney Disease/Dialysis: Can sometimes lead to copper loss.

Symptoms of Low Copper Levels:

Symptoms of copper deficiency often manifest gradually and can be mistaken for other conditions:

- Anemia: A unique type of anemia that doesn't respond to iron supplementation, characterized by low white blood cell count (neutropenia).

- Neurological problems: Peripheral neuropathy (numbness, tingling), myelopathy (spinal cord dysfunction leading to gait disturbances), ataxia (lack of coordination), cognitive decline.

- Bone abnormalities: Osteoporosis, increased fracture risk, especially in children.

- Hair and skin changes: Fragile hair, depigmentation of hair and skin.

- Immune dysfunction: Increased susceptibility to infections.

- Cardiovascular issues: Impaired heart function.

Potential Dangers of Low Copper Levels:

Untreated copper deficiency can lead to irreversible neurological damage, severe anemia, and weakened bones. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial to prevent long-term complications.

Dietary Sources of Copper

A balanced diet is usually sufficient to meet the body's copper requirements. The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for adults is 900 micrograms (µg) per day.

Rich Dietary Sources:

- Organ Meats: Liver (beef, lamb, pork) is exceptionally rich in copper.

- Shellfish: Oysters, crab, lobster, mussels are excellent sources.

- Nuts and Seeds: Cashews, almonds, sesame seeds, sunflower seeds, and chia seeds.

- Legumes: Lentils, chickpeas, and beans.

- Whole Grains: Oats, quinoa, and whole wheat products.

- Dark Chocolate: A delicious source of copper.

- Certain Vegetables: Mushrooms, potatoes, and leafy greens.

- Fruits: Avocados and some dried fruits.

Incorporating a variety of these foods into your diet can help ensure adequate copper intake.

Copper Bioavailability

Bioavailability refers to the proportion of a nutrient that is absorbed from the diet and utilized by the body. Several factors can influence copper absorption and metabolism.

Factors Affecting Copper Absorption:

- Dietary Factors:

- Zinc: As mentioned, excessive zinc intake is a major inhibitor of copper absorption. They compete for the same transport proteins in the gut.

- Iron: Very high doses of iron supplements can interfere with copper absorption.

- Molybdenum: Can interact with copper, particularly at high levels, leading to complex formation that reduces copper availability.

- Phytates: Found in whole grains, legumes, and nuts, can bind to copper and other minerals, reducing their absorption. Soaking, sprouting, or fermenting these foods can help reduce phytate content.

- Fiber: High fiber intake might slightly reduce copper absorption, though usually not to a clinically significant degree in a balanced diet.

- Vitamin C: High doses of vitamin C (over 1500 mg/day) have been shown in some studies to interfere with copper absorption, though this is debated.

- Individual Factors:

- Age: Absorption rates can vary with age.

- Gastrointestinal Health: Conditions affecting the gut lining (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease) can impair absorption.

- Genetic Factors: Genetic predispositions, such as those in Menkes disease, severely impact copper transport.

Enhancers of Copper Absorption:

Generally, copper absorption is tightly regulated, and the body adjusts absorption based on its needs. There aren't specific "enhancers" in the same way there are for iron (e.g., vitamin C). However, a healthy gut microbiome and balanced diet support optimal nutrient absorption overall.

Copper Supplementation

Copper supplementation should only be considered under the guidance of a healthcare professional, especially after a confirmed diagnosis of copper deficiency. Self-supplementation can be risky due to the potential for toxicity or the induction of other mineral imbalances, particularly with zinc.

When is Copper Supplementation Indicated?

- Diagnosed Copper Deficiency: Confirmed by blood tests and clinical symptoms.

- Menkes Disease: While not a "supplementation" in the traditional sense, high doses of copper injections are used to try and bypass the absorption defect.

- Post-Bariatric Surgery: Prophylactic copper supplementation may be recommended due to malabsorption risks.

- Chronic Diarrhea or Malabsorption Syndromes: If dietary intake and absorption are insufficient.

Forms of Copper Supplements:

Common forms include:

- Copper Gluconate: A widely available and generally well-absorbed form.

- Copper Sulfate: Another common form, often used in multivitamin/mineral supplements.

- Copper Citrate: Also considered a bioavailable form.

- Copper Chelate (e.g., Copper Bisglycinate): Copper bound to amino acids, often marketed for improved absorption.

- Cupric Oxide: Generally considered to have poor bioavailability and is not recommended as a supplement.

Dosage Considerations:

Therapeutic doses for treating deficiency are typically much higher than the RDA and must be determined by a physician. For example, doses ranging from 2-8 mg per day might be prescribed for deficiency, significantly exceeding the 900 µg (0.9 mg) RDA. It is crucial not to exceed prescribed doses due to the risk of toxicity.

Risks of Excessive Supplementation:

Taking too much copper can lead to toxicity (copper poisoning), which can cause severe symptoms including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and in severe cases, liver damage, kidney failure, and neurological problems. Furthermore, high copper intake can interfere with the absorption and utilization of other essential minerals, most notably zinc and iron, potentially leading to secondary deficiencies. Always consult a healthcare provider before starting any copper supplement.

Maintaining Healthy Copper Levels

Achieving and maintaining healthy copper levels is a balance.

- Balanced Diet: Focus on a diverse diet rich in whole foods, including those known to be good sources of copper.

- Avoid Excessive Zinc: Be mindful of zinc supplementation. While zinc is essential, high doses (e.g., >40 mg/day for prolonged periods) can induce copper deficiency. If you take zinc supplements, ensure they are balanced with an appropriate amount of copper, or consult your doctor.

- Regular Check-ups: If you have underlying health conditions, take certain medications, or have undergone bariatric surgery, discuss regular copper level monitoring with your doctor.

Conclusion

Copper is an indispensable mineral, crucial for a vast array of bodily functions. Its levels are tightly regulated, and imbalances—both deficiency and excess—can have profound health implications. Understanding the normal reference ranges, recognizing the symptoms of abnormal levels, and being aware of dietary and supplemental considerations are key steps in maintaining optimal copper status. Always interpret your copper test results in consultation with a healthcare professional, who can provide personalized advice based on your complete medical history.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of abnormal Copper levels?

The most common cause of low copper levels (deficiency) in the general population is often excessive zinc intake from supplements, as zinc competes with copper for absorption. Other causes include malabsorption syndromes or bariatric surgery. For high copper levels (excess), the most common causes are acute or chronic inflammation and certain liver diseases that impair copper excretion. A less common but medically significant cause of severe copper overload is the genetic condition Wilson's disease.

How often should I get my Copper tested?

For most healthy individuals, routine copper testing is not necessary. Testing is typically recommended when there is a clinical suspicion of deficiency or toxicity, based on symptoms or risk factors (e.g., malabsorption, excessive zinc supplementation, unexplained anemia, or neurological symptoms). If you have a diagnosed copper imbalance or a condition like Wilson's disease, your doctor will establish a regular monitoring schedule, which could range from every few months to annually, depending on your condition and treatment plan. Always discuss your specific needs with your healthcare provider.

Can lifestyle changes improve my Copper levels?

Yes, lifestyle changes, primarily dietary adjustments, can significantly impact copper levels.

- For low copper levels: Increasing your intake of copper-rich foods (organ meats, shellfish, nuts, seeds, dark chocolate, legumes) can help. Additionally, if excessive zinc intake is the cause, reducing or discontinuing high-dose zinc supplements is crucial.

- For high copper levels (non-genetic): While dietary copper restriction is generally not the primary treatment unless intake is excessively high, avoiding copper-rich foods might be advised in severe cases. The most effective lifestyle change often involves addressing the underlying cause, such as managing liver disease or reducing inflammation. For genetic conditions like Wilson's disease, medical chelation therapy is necessary, not just lifestyle changes. Always consult with a doctor or registered dietitian for personalized dietary advice regarding copper.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Always consult a healthcare professional.