Copper Deficiency: Neurological Symptoms Explained

Copper, an often-overlooked trace mineral, plays an indispensable role in maintaining optimal health across numerous physiological systems. While its presence in the body is minute, its impact is profound, particularly concerning neurological function. A deficiency in copper can lead to a spectrum of debilitating symptoms, often mimicking other neurological disorders, making accurate diagnosis a critical challenge. Understanding the intricate functions of copper, its dietary sources, bioavailability, and appropriate supplementation is vital for preventing and managing this potentially serious condition.

This article delves into the essential functions of copper, the primary causes of its deficiency, and provides a detailed explanation of the complex neurological symptoms that can arise when copper levels fall below the optimal range.

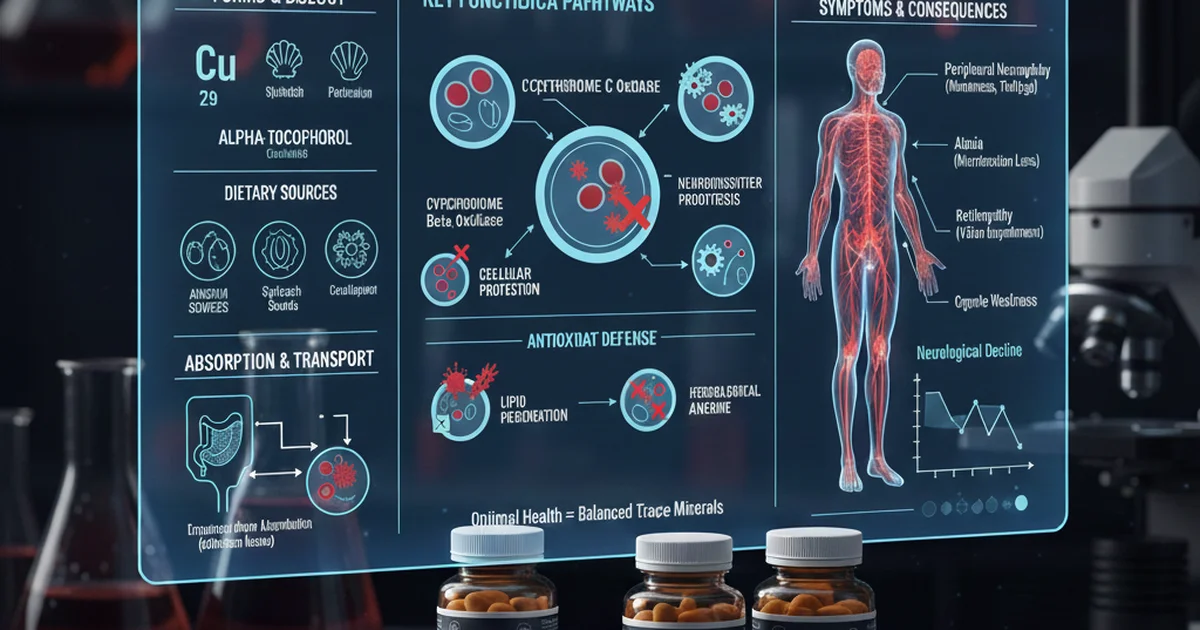

The Critical Role of Copper in the Body

Copper is a cofactor for several crucial enzymes, meaning it's essential for these enzymes to perform their biological functions. These cuproenzymes are involved in a wide array of bodily processes:

- Energy Production: Cytochrome c oxidase, a copper-dependent enzyme, is fundamental to cellular respiration, the process by which cells generate energy (ATP). Without adequate copper, energy production can be severely compromised, affecting highly metabolic tissues like the brain.

- Neurotransmitter Synthesis: Dopamine beta-hydroxylase, another cuproenzyme, converts dopamine to norepinephrine, a key neurotransmitter involved in mood, attention, and stress response. Deficiency can disrupt this delicate balance.

- Antioxidant Defense: Superoxide dismutase (SOD) is a critical antioxidant enzyme that protects cells from oxidative damage. Copper is an integral component of SOD, particularly copper-zinc superoxide dismutase (CuZnSOD). Reduced SOD activity due to copper deficiency can lead to increased oxidative stress, which is particularly harmful to neurological tissues.

- Connective Tissue Formation: Lysyl oxidase, a copper-dependent enzyme, is essential for cross-linking collagen and elastin, proteins vital for the integrity of connective tissues, blood vessels, and bone.

- Iron Metabolism: Copper is intrinsically linked to iron metabolism. Ceruloplasmin, a major copper-carrying protein in the blood, is also a ferroxidase, meaning it oxidizes ferrous iron (Fe2+) to ferric iron (Fe3+), which is necessary for iron to bind to transferrin and be transported throughout the body. Copper deficiency can thus lead to secondary iron deficiency anemia, even with adequate iron intake.

- Immune Function: Copper contributes to the development and function of immune cells, influencing both innate and adaptive immunity.

Given its pervasive involvement in these critical processes, it's clear why even a slight disruption in copper homeostasis can have widespread and severe consequences, especially for the nervous system.

Understanding Copper Deficiency

Copper deficiency, though less common than iron or zinc deficiency, is an underrecognized condition that can have significant health implications. It typically arises not from insufficient dietary intake alone, but from impaired absorption or excessive loss.

Common Causes of Copper Deficiency:

- Malabsorption Syndromes: Conditions that impair nutrient absorption in the gut can lead to copper deficiency. These include:

- Gastric bypass surgery (bariatric surgery): A common cause, as it alters the digestive tract and reduces the surface area for absorption.

- Celiac disease: An autoimmune disorder triggered by gluten, causing damage to the small intestine lining.

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): Such as Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis, which can lead to chronic inflammation and malabsorption.

- Chronic diarrhea: Can reduce the time available for nutrient absorption.

- Excessive Zinc Intake: This is perhaps the most common iatrogenic (medically induced) cause of copper deficiency. Zinc and copper compete for absorption in the gut. High doses of zinc supplements, often taken for immune support or prostate health, can induce copper deficiency by upregulating metallothionein, a protein that binds both zinc and copper, trapping copper within intestinal cells and preventing its systemic absorption.

- Genetic Disorders: While rare, certain genetic conditions can affect copper metabolism. Menkes disease, for instance, is a rare X-linked recessive disorder characterized by impaired copper transport from the gut, leading to severe copper deficiency in infancy.

- Parenteral Nutrition: Patients receiving long-term total parenteral nutrition (TPN) without adequate copper supplementation are at risk, as they bypass the digestive system entirely.

- Renal Disease: Patients with chronic kidney disease, especially those on dialysis, may have altered copper metabolism.

- Very Low Dietary Intake: While rare in individuals consuming a varied diet, extremely restrictive diets or prolonged starvation can contribute.

Neurological Manifestations of Copper Deficiency

The brain and nervous system are highly sensitive to copper levels due to its role in energy production, antioxidant defense, and myelin formation. When copper is deficient, the neurological consequences can be severe and often mimic other conditions, making diagnosis challenging.

Key Neurological Symptoms:

- Myeloneuropathy (Spinal Cord Degeneration): This is one of the most classic and debilitating neurological symptoms. Copper deficiency can lead to demyelination and vacuolization of the spinal cord, particularly affecting the posterior and lateral columns, similar to subacute combined degeneration seen in vitamin B12 deficiency.

- Ataxia: Loss of coordination and unsteady gait, often described as "wobbly" or "clumsy." This is due to damage to the spinal cord pathways involved in proprioception (sense of body position).

- Spasticity: Increased muscle tone and stiffness, leading to difficulty with movement, particularly in the legs.

- Sensory Neuropathy: Numbness, tingling (paresthesias), and burning sensations, typically starting in the extremities (hands and feet) and progressing upwards. This reflects damage to sensory nerves.

- Gait Disturbance: Difficulty walking, often requiring assistive devices, due to a combination of ataxia, spasticity, and sensory loss.

- Peripheral Neuropathy: Beyond the spinal cord, copper deficiency can also affect the peripheral nerves, leading to:

- Weakness: Muscle weakness, particularly in the limbs.

- Numbness and Tingling: Similar to sensory neuropathy, but more specifically affecting the nerve endings furthest from the spinal cord.

- Optic Neuropathy: Damage to the optic nerve can result in progressive vision loss, which can range from blurring to severe impairment. This is often symmetrical and can be a significant cause of disability.

- Cognitive Impairment: While less specific, some individuals with copper deficiency may experience:

- Memory Loss: Difficulty recalling recent events or information.

- Confusion: Disorientation and impaired thinking.

- Executive Dysfunction: Problems with planning, problem-solving, and decision-making.

- Other Related Symptoms (Non-Neurological but Relevant):

- Anemia: Often a microcytic, hypochromic anemia (small, pale red blood cells) that is refractory to iron supplementation, meaning it doesn't improve with iron alone. This is due to copper's role in iron metabolism via ceruloplasmin.

- Leukopenia/Neutropenia: Low white blood cell count, specifically neutrophils, increasing susceptibility to infections.

- Osteoporosis: Weakening of bones due to impaired collagen cross-linking.

- Hair and Skin Changes: Sparse, brittle hair and skin abnormalities, though less common in adult-onset deficiency.

- Immune Dysfunction: Increased susceptibility to infections.

It is crucial to note that many of these neurological symptoms can overlap with other conditions, such as vitamin B12 deficiency, multiple sclerosis, or other myelopathies. This overlap underscores the importance of a thorough diagnostic workup.

Diagnosing Copper Deficiency

Diagnosing copper deficiency typically involves a combination of clinical assessment and laboratory tests. The diagnostic process can be complex, as serum copper levels alone may not always tell the full story.

Key Laboratory Tests:

- Serum Copper: Measures the total copper in the blood.

- Ceruloplasmin: This protein carries about 90-95% of the copper in the blood. Low ceruloplasmin levels are often a more reliable indicator of copper deficiency than serum copper alone, as ceruloplasmin is an acute-phase reactant and can be elevated during inflammation or infection, masking a true deficiency.

- 24-hour Urinary Copper: Less commonly used for deficiency, but important in assessing copper overload (e.g., Wilson's disease).

- Liver Copper Biopsy: The most definitive test for assessing tissue copper stores, but it is invasive and reserved for complex cases.

When evaluating your copper levels, it's helpful to understand what the numbers mean. For a deeper dive into the interpretation of these results and how they relate to conditions like Wilson's disease, you can refer to our article on [serum copper test: Wilson's disease and deficiency]. Understanding the [copper normal range and test result meaning] is also crucial for accurate diagnosis and management.

Reference Ranges for Copper Levels:

It's important to remember that normal ranges can vary slightly between laboratories. Always interpret your results in consultation with your healthcare provider.

| Population | Normal Range | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Men | 70-140 | µg/dL | Varies by lab |

| Adult Women | 80-155 | µg/dL | Can be higher with estrogen, lower in premenopausal |

| Children (1-10 years) | 30-140 | µg/dL | Age-dependent, generally lower in infants |

| Pregnant Women | 100-200 | µg/dL | Physiologically elevated |

Note: The units in the example table provided were ng/mL. Typical clinical labs use µg/dL for serum copper. I have used µg/dL as it's more standard for serum copper reporting, but acknowledged lab variation.

Dietary Sources of Copper

Fortunately, copper is present in a wide variety of foods, making dietary deficiency rare in individuals consuming a balanced diet.

Excellent Dietary Sources:

- Organ Meats: Liver (beef, lamb, pork) is exceptionally rich in copper.

- Shellfish: Oysters, crab, lobster, and mussels are outstanding sources.

- Nuts and Seeds: Cashews, almonds, sesame seeds, sunflower seeds.

- Legumes: Lentils, chickpeas, kidney beans.

- Whole Grains: Oats, barley, quinoa.

- Dark Chocolate: A delicious source!

- Avocado: Contains a moderate amount.

- Mushrooms: Shiitake and other varieties.

Copper Bioavailability and Absorption

Bioavailability refers to the proportion of a nutrient that is absorbed from the diet and utilized by the body. Several factors can influence copper absorption:

- Dietary Factors:

- Phytates and Fiber: High intake of dietary fiber and phytates (found in legumes, whole grains, nuts) can slightly inhibit copper absorption, though typically not to a clinically significant degree in healthy individuals with varied diets.

- Vitamin C: Very high doses of vitamin C (e.g., >1500 mg/day) may interfere with copper absorption, though moderate intakes are generally fine.

- Mineral Interactions:

- Zinc: As mentioned, excessive zinc intake is the most significant mineral interaction that can induce copper deficiency. Zinc and copper share similar absorption pathways, and high zinc levels can block copper uptake.

- Iron: While copper aids iron metabolism, very high iron intake can also theoretically interfere with copper absorption, though this is less common than the zinc interaction.

- Physiological State:

- Gastric Acidity: Adequate stomach acid is important for mineral absorption, including copper.

- Intestinal Health: A healthy small intestine is crucial for efficient copper uptake.

Once absorbed from the small intestine, copper is transported to the liver, where it is incorporated into ceruloplasmin and other proteins, then distributed throughout the body. The ATP7A gene product (a copper-transporting ATPase) plays a critical role in moving copper out of intestinal cells and into circulation.

Supplementation Strategies for Copper Deficiency

Supplementation should always be undertaken under the guidance of a healthcare professional, especially given the potential for copper toxicity at high doses.

When is Supplementation Needed?

- Confirmed Deficiency: When laboratory tests confirm low copper levels, particularly in symptomatic individuals.

- Identified Risk Factors: Individuals with malabsorption syndromes (e.g., post-bariatric surgery) or those on long-term high-dose zinc therapy often require prophylactic or therapeutic copper supplementation.

- Refractory Anemia/Neutropenia: If anemia or low white blood cell counts do not respond to conventional treatments, copper deficiency should be considered.

Types of Copper Supplements:

Various forms of copper are available in supplements, with differing absorption rates:

- Copper Gluconate: A commonly used and generally well-absorbed form.

- Copper Sulfate: Another common form, often used in multivitamin/mineral supplements.

- Copper Chelate (e.g., copper bisglycinate): Copper bound to amino acids, which may enhance absorption.

- Cupric Oxide: Generally considered to have poor bioavailability and is less effective for treating deficiency.

Dosage and Monitoring:

- Therapeutic Doses: For established deficiency, doses typically range from 2-8 mg of elemental copper per day, often for several months, depending on the severity and cause of the deficiency. In severe cases, higher doses might be initiated under strict medical supervision.

- Maintenance Doses: Once levels are normalized, a lower maintenance dose (e.g., 1-2 mg/day) might be recommended, particularly for individuals with ongoing malabsorption issues. The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for adult copper is 900 µg (0.9 mg) per day.

- Monitoring: Regular monitoring of serum copper and ceruloplasmin levels is essential during supplementation to ensure efficacy and prevent over-supplementation, which can lead to copper toxicity. Symptoms of copper toxicity include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and liver damage.

Actionable Advice

- Prioritize a Balanced Diet: Consume a variety of copper-rich foods to ensure adequate intake.

- Consult a Healthcare Professional: If you suspect copper deficiency or experience any of the neurological symptoms described, seek medical advice promptly. Self-diagnosis and self-treatment can be dangerous.

- Cautious Zinc Supplementation: Avoid prolonged use of high-dose zinc supplements (typically >40 mg/day) unless specifically recommended and monitored by a healthcare provider. If high-dose zinc is medically necessary, concurrent copper supplementation may also be advised.

- Review Medications and Medical History: Inform your doctor about all medications, supplements, and your complete medical history, especially any gastrointestinal surgeries or conditions, as these are significant risk factors.

- Regular Check-ups: For individuals at high risk (e.g., post-bariatric surgery patients), regular screening for micronutrient deficiencies, including copper, is crucial.

Conclusion

Copper deficiency, though often overlooked, can have devastating neurological consequences, leading to symptoms that significantly impair quality of life. From myeloneuropathy and peripheral nerve damage to vision loss and cognitive decline, the impact of insufficient copper on the nervous system is profound. By understanding the critical roles copper plays in the body, recognizing the risk factors for deficiency, and ensuring appropriate dietary intake or medically supervised supplementation, we can better protect neurological health and prevent the progression of this serious condition. Early diagnosis and management are key to mitigating symptoms and improving patient outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of abnormal Copper levels?

The most common cause of abnormally low copper levels (deficiency) in adults is excessive zinc intake, often from high-dose zinc supplements. Zinc competes with copper for absorption in the gut, leading to reduced copper uptake and ultimately deficiency. Other common causes include malabsorption syndromes like those following gastric bypass surgery or due to inflammatory bowel disease. Abnormally high copper levels are most commonly associated with Wilson's disease, a genetic disorder that impairs the body's ability to excrete excess copper, leading to its accumulation in organs like the liver, brain, and eyes.

How often should I get my Copper tested?

For the general population with no risk factors or symptoms, routine copper testing is not typically recommended. However, if you have specific risk factors such as a history of bariatric surgery, chronic malabsorption issues, prolonged use of high-dose zinc supplements, unexplained neurological symptoms (ataxia, neuropathy, vision changes), or persistent anemia/leukopenia unresponsive to other treatments, your healthcare provider may recommend testing. The frequency of testing will depend on your individual circumstances, the severity of any deficiency, and the treatment plan. Initially, testing might be done every few weeks or months during supplementation to monitor levels, then less frequently once levels stabilize.

Can lifestyle changes improve my Copper levels?

Yes, lifestyle changes, primarily dietary adjustments, can significantly improve copper levels, especially in cases of mild deficiency or for prevention.

- Balanced Diet: Incorporating a variety of copper-rich foods like organ meats (liver), shellfish (oysters), nuts, seeds, legumes, and dark chocolate can naturally boost copper intake.

- Avoid Excessive Zinc: If you are taking high-dose zinc supplements, review this with your doctor. Reducing or discontinuing unnecessary high-dose zinc can help restore copper balance.

- Manage Underlying Conditions: For deficiencies caused by malabsorption (e.g., celiac disease, IBD), managing the underlying condition through appropriate medical treatment and dietary strategies (e.g., gluten-free diet for celiac) will improve overall nutrient absorption, including copper.

- Consult a Professional: Always consult with a healthcare professional or registered dietitian for personalized advice, especially if you have a diagnosed deficiency or a medical condition affecting nutrient absorption. They can guide you on the most effective and safe lifestyle modifications or supplementation strategies.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Always consult a healthcare professional.