Zinc Blood Test: Detecting Deficiency and Toxicity

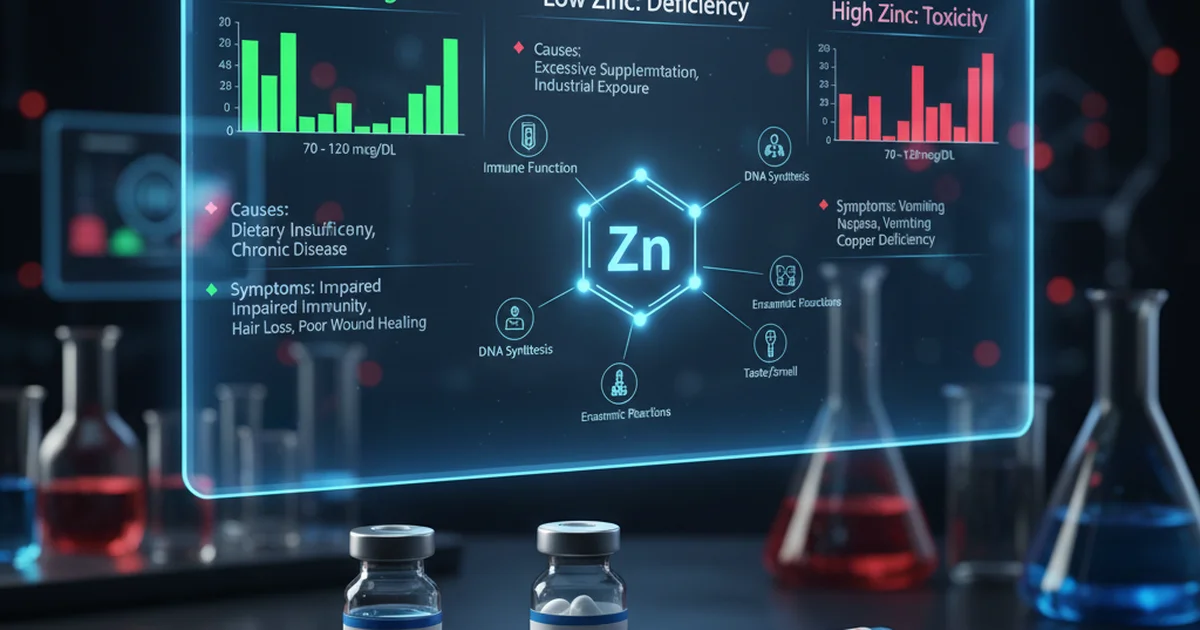

Direct answer: A zinc blood test measures the amount of zinc in your serum or plasma to detect potential deficiency or toxicity. However, results can be misleading as levels are affected by inflammation, diet, and time of day, so they don't always reflect your body's total zinc stores.

TL;DR A zinc blood test is the primary tool for assessing your body's zinc status, but interpreting the results requires care. Zinc is an essential mineral vital for immune function, wound healing, and growth. While the test can indicate a deficiency or toxicity, the level of zinc in your blood can be temporarily lowered by factors like inflammation, stress, or recent meals, meaning a low result doesn't always confirm a chronic deficiency. Similarly, high levels usually point to excessive supplementation and can interfere with copper absorption, leading to other health issues like anemia.

- What it is: A blood test measuring zinc concentration in your serum or plasma.

- Why it's done: To diagnose zinc deficiency (common) or toxicity (rare, usually from supplements).

- Symptoms of Deficiency: Frequent infections, poor wound healing, hair loss, and loss of taste or smell.

- Symptoms of Toxicity: Nausea, stomach cramps, and long-term risk of copper deficiency and anemia.

- Test Limitations: Blood levels don't always reflect total body stores and can be skewed by illness or diet.

- Best Sources: Oysters, red meat, and poultry offer highly absorbable zinc.

- Key Takeaway: Test results must be considered alongside your symptoms, diet, and overall health.

Want the full explanation? Keep reading ↓

Zinc, an essential trace mineral, plays a pivotal role in maintaining human health, influencing countless biological processes from immune function to DNA synthesis. Despite its critical importance, zinc deficiency is remarkably common globally, while excessive intake can lead to toxicity. A zinc blood test serves as a crucial diagnostic tool to assess an individual's zinc status, guiding dietary and supplementation strategies to prevent or correct imbalances. Understanding the nuances of zinc metabolism, its dietary sources, and the interpretation of test results is paramount for optimal health management.

Understanding Zinc's Role in the Body

Zinc is a ubiquitous nutrient, acting as a co-factor for over 300 enzymes and participating in more than 2,000 transcription factors. Its diverse functions underscore its fundamental importance:

- Enzymatic Functions: Zinc is integral to enzymes involved in metabolism, digestion, nerve function, and many other processes. These enzymes are vital for breaking down carbohydrates, fats, and proteins, and for cellular energy production.

- Immune System Modulation: Zinc is critical for the proper development and function of immune cells, including T-lymphocytes and natural killer cells. It helps regulate immune responses, reducing inflammation and enhancing the body's ability to fight off infections. Chronic zinc deficiency significantly impairs immune function, making individuals more susceptible to various pathogens.

- Wound Healing: Zinc is essential for cell proliferation, collagen synthesis, and immune responses at the wound site, all of which are crucial for effective tissue repair.

- DNA Synthesis and Cell Division: As a component of enzymes involved in DNA and RNA synthesis, zinc is fundamental for cell growth, division, and repair. This makes it particularly important during periods of rapid growth, such as childhood, adolescence, and pregnancy.

- Growth and Development: Adequate zinc is necessary for normal growth and development in children and adolescents, influencing bone growth, sexual maturation, and overall physical development.

- Sensory Functions: Zinc is required for the proper function of taste buds and olfactory receptors, playing a role in maintaining a sense of taste and smell. Deficiency can lead to altered or diminished sensory perception.

- Antioxidant Defense: Zinc contributes to antioxidant defense systems by supporting the enzyme superoxide dismutase, which helps protect cells from oxidative damage caused by free radicals.

Zinc Deficiency: Causes, Symptoms, and Consequences

Zinc deficiency can arise from various factors, ranging from inadequate dietary intake to impaired absorption or increased loss. Recognizing its signs and understanding its long-term consequences is vital.

Causes of Zinc Deficiency

- Inadequate Dietary Intake: The most common cause, especially in populations relying heavily on refined grains and plant-based diets high in phytates (compounds that inhibit zinc absorption). Vegetarians and vegans are at higher risk if not carefully planning their diets.

- Malabsorption Syndromes: Conditions like Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, celiac disease, short bowel syndrome, and chronic diarrhea can impair zinc absorption from the gut.

- Increased Loss: Chronic kidney disease, excessive sweating, and certain medications (e.g., diuretics) can lead to increased zinc excretion.

- Increased Requirements: Pregnancy, lactation, rapid growth periods in children, and chronic illnesses (e.g., liver disease, sickle cell anemia) increase the body's demand for zinc.

- Alcoholism: Chronic alcohol consumption interferes with zinc absorption and increases its urinary excretion.

- Genetic Disorders: Acrodermatitis enteropathica is a rare genetic disorder characterized by severe zinc malabsorption, leading to profound deficiency symptoms from infancy.

Symptoms of Zinc Deficiency

Symptoms can be varied and non-specific, often overlapping with other nutritional deficiencies, making diagnosis challenging without testing.

- Immune Dysfunction: Frequent infections, prolonged illness, poor wound healing.

- Skin and Hair Problems: Dermatitis, acne, psoriasis-like lesions, slow wound healing, hair loss (alopecia).

- Growth Retardation: Stunted growth and delayed sexual maturation in children and adolescents.

- Gastrointestinal Issues: Chronic diarrhea, loss of appetite.

- Neurological and Sensory Impairments: Impaired taste (hypogeusia) and smell (hyposmia), night blindness, lethargy, mental apathy.

- Reproductive Issues: Male infertility due to impaired sperm production.

- Anemia: Though less common, zinc deficiency can sometimes contribute to anemia by interfering with iron metabolism.

Consequences of Chronic Zinc Deficiency

Untreated chronic zinc deficiency can lead to severe health problems, including persistent immune compromise, increased risk of infections, permanent growth stunting, and neurological damage, particularly in children. It can also exacerbate the severity and duration of common infections like the common cold and influenza.

Zinc Toxicity: Causes, Symptoms, and Consequences

While less common than deficiency, excessive zinc intake can also be detrimental to health, typically resulting from high-dose supplementation.

Causes of Zinc Toxicity

- Excessive Supplementation: The most frequent cause. Taking zinc supplements significantly above the Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL), which is 40 mg/day for adults, can lead to toxicity. Some therapeutic regimens might transiently exceed this, but always under strict medical supervision.

- Industrial Exposure: Inhalation of zinc fumes in industrial settings (e.g., welding) can cause "metal fume fever," a temporary illness with flu-like symptoms.

- Ingestion of Zinc-Containing Products: Accidental ingestion of large quantities of zinc-containing products (e.g., denture creams containing high levels of zinc) can lead to toxicity.

Symptoms of Zinc Toxicity

Symptoms often manifest acutely after a large dose or chronically with sustained high intake.

- Gastrointestinal Distress: Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal cramps.

- Copper Deficiency: High zinc intake can interfere with copper absorption by inducing metallothionein in the intestine, which binds both zinc and copper, but has a higher affinity for copper, effectively trapping it and preventing its absorption. This is one of the most serious long-term consequences.

- Immune Suppression: Paradoxically, while moderate zinc supports immunity, excessive zinc can suppress immune function.

- Neurological Symptoms: Headache, dizziness, lethargy.

- Anemia: Due to induced copper deficiency, which is essential for iron metabolism, microcytic hypochromic anemia can develop.

Consequences of Chronic Zinc Toxicity

Chronic zinc toxicity primarily leads to secondary copper deficiency, which can result in severe neurological dysfunction (myelopathy, peripheral neuropathy), hematological abnormalities (anemia, neutropenia), and cardiac issues. These conditions can be debilitating and, if unrecognized, potentially irreversible.

The Zinc Blood Test: What It Measures

The primary method for assessing zinc status is a serum or plasma zinc test. This measures the concentration of zinc circulating in the blood.

- Serum vs. Plasma Zinc: While both are used, plasma zinc levels are generally slightly higher than serum levels. The method used (serum or plasma) should be consistent for serial measurements.

- Limitations: Serum/plasma zinc levels are influenced by several factors and may not always accurately reflect total body zinc stores. Acute inflammation, stress, and time of day can all affect circulating zinc levels. For instance, zinc is an acute-phase reactant, meaning its levels can decrease during inflammation, even if overall body stores are adequate. Albumin levels also play a role, as a significant portion of circulating zinc is bound to albumin.

- Other Measures:

- Erythrocyte (red blood cell) zinc: May provide a better indicator of longer-term zinc status than serum zinc, but it is not routinely available and is more technically challenging.

- Hair zinc: Can reflect long-term exposure but is often unreliable due to external contamination and lack of standardization.

- Urinary zinc: Primarily used to assess zinc excretion, not body stores.

Preparation for the Test

- Fasting: Typically, a fasting blood sample (8-12 hours) is preferred as recent meals can affect zinc levels.

- Timing: Zinc levels exhibit diurnal variation, with lower concentrations in the morning. A consistent time of day for testing is recommended for serial measurements.

- Medications/Supplements: Inform your doctor about any medications, vitamins, or mineral supplements you are taking, as some can interfere with zinc levels or test results.

Interpreting Zinc Blood Test Results

Interpreting zinc blood test results requires careful consideration of the reference ranges, clinical symptoms, and other influencing factors.

Reference Ranges for Serum/Plasma Zinc

These ranges can vary slightly between laboratories due to different analytical methods and populations studied. Always refer to the specific reference range provided by the testing laboratory.

| Population | Normal Range | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Men | 70-120 | µg/dL | Varies by lab and time of day |

| Adult Women | 65-115 | µg/dL | Can be lower in pregnancy |

| Children (1-10 yrs) | 60-100 | µg/dL | Age-dependent, lower in infants |

| Adolescents (11-17 yrs) | 65-110 | µg/dL | Influenced by growth spurts |

Note: µg/dL = micrograms per deciliter

Factors Affecting Results

- Time of Day: Zinc levels are typically lower in the morning.

- Inflammation/Infection: Acute inflammatory states can cause a temporary decrease in serum zinc, as zinc is sequestered by the liver. This means a low zinc level during an acute illness might not reflect chronic deficiency.

- Albumin Levels: Hypoalbuminemia (low albumin) can lead to artificially low total serum zinc levels, as most circulating zinc is bound to albumin.

- Hemolysis: Rupture of red blood cells during blood collection can release intracellular zinc, leading to falsely elevated results.

- Dietary Intake: Recent high zinc intake can temporarily elevate serum levels.

- Medications: Certain drugs, such as corticosteroids and some chelating agents, can affect zinc levels.

Clinical context is paramount. A low zinc level in a symptomatic individual strongly suggests deficiency, whereas a low level in an asymptomatic individual might warrant further investigation or consideration of confounding factors. Similarly, high zinc levels must be correlated with symptoms of toxicity and an assessment of dietary or supplemental intake.

Dietary Sources of Zinc and Bioavailability

Ensuring adequate zinc intake through diet is the cornerstone of preventing deficiency. Bioavailability, or the proportion of zinc absorbed and utilized by the body, varies significantly depending on the food source and dietary composition.

Animal Sources

Animal-based foods are generally excellent sources of highly bioavailable zinc.

- Oysters: By far the richest dietary source of zinc.

- Red Meat: Beef, lamb, and pork are significant contributors to zinc intake.

- Poultry: Chicken and turkey, especially darker meat, contain good amounts of zinc.

- Seafood: Crab, lobster, and other shellfish.

- Eggs and Dairy: Provide moderate amounts of zinc.

Plant Sources

While many plant foods contain zinc, its bioavailability can be lower due to the presence of inhibitors.

- Legumes: Lentils, chickpeas, black beans, kidney beans. Soaking, sprouting, and fermentation can improve zinc absorption from legumes by reducing phytate content.

- Nuts and Seeds: Pumpkin seeds, cashews, almonds, hemp seeds.

- Whole Grains: Oats, quinoa, brown rice, whole wheat bread. Like legumes, whole grains contain phytates.

- Certain Vegetables: Potatoes, green beans, kale.

Bioavailability Factors

- Enhancers of Absorption:

- Animal Protein: The presence of animal protein enhances zinc absorption.

- Citric Acid and Other Organic Acids: Found in fruits and vegetables, these can form soluble complexes with zinc, improving absorption.

- Inhibitors of Absorption:

- Phytates (Phytic Acid): Found in whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds, phytates bind to zinc, forming insoluble complexes that reduce its absorption. This is a primary concern for vegetarians and vegans.

- High Fiber Intake: Can sometimes reduce zinc absorption, though the effect is often linked to phytate content.

- Iron Supplements: High doses of iron supplements can compete with zinc for absorption. It's often recommended to take iron and zinc at different times of the day if both are supplemented.

- Calcium: Very high calcium intake can modestly inhibit zinc absorption.

To maximize zinc absorption from plant-based foods, techniques like soaking, sprouting, and fermenting legumes and grains can be beneficial, as they help break down phytates.

Zinc Supplementation: When and How

Zinc supplementation should ideally be guided by a healthcare professional, especially when addressing a diagnosed deficiency or specific medical conditions.

Indications for Supplementation

- Confirmed Zinc Deficiency: Based on blood tests and clinical symptoms.

- Malabsorption Syndromes: Individuals with conditions like Crohn's disease, celiac disease, or chronic diarrhea.

- Vegetarian/Vegan Diets: If dietary intake is consistently low and symptoms of deficiency are present.

- Pregnancy and Lactation: To meet increased demands, under medical guidance.

- Certain Chronic Diseases: Liver disease, sickle cell anemia, chronic kidney disease, where zinc metabolism may be impaired.

- Support for Immune Function: In some cases, short-term supplementation may be recommended during acute infections, but this should not be a long-term strategy without medical advice.

- Acrodermatitis Enteropathica: Requires lifelong high-dose zinc supplementation.

Types of Zinc Supplements

Zinc is available in various forms, each with different elemental zinc content and absorption rates.

- Zinc Gluconate: One of the most common forms, often used in lozenges for colds. Contains about 14% elemental zinc.

- Zinc Picolinate: Often marketed for superior absorption, though evidence is mixed. Contains about 20% elemental zinc.

- Zinc Citrate: Well-absorbed form, commonly found in supplements. Contains about 31% elemental zinc.

- Zinc Sulfate: A less expensive form, but can cause more gastrointestinal upset. Contains about 23% elemental zinc.

- Zinc Acetate: Another common form, also used in lozenges. Contains about 30% elemental zinc.

Always check the elemental zinc content on the supplement label, as this is what determines the actual dose you are receiving. For example, 50 mg of zinc sulfate does not mean 50 mg of elemental zinc.

Dosage Considerations

- Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA):

- Adult Men: 11 mg/day

- Adult Women: 8 mg/day (11 mg/day during pregnancy, 12 mg/day during lactation)

- Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL): For adults, the UL is 40 mg/day of elemental zinc from supplements and diet combined. Exceeding this regularly increases the risk of toxicity, particularly copper deficiency.

- Therapeutic Doses: For diagnosed deficiencies, higher doses (e.g., 25-50 mg elemental zinc/day) may be prescribed by a doctor for a limited period, followed by re-evaluation. Such doses should always be taken under medical supervision.

Precautions and Interactions

- Copper Balance: As discussed, high-dose zinc can induce copper deficiency. If taking high-dose zinc (e.g., >30 mg elemental zinc/day) for an extended period, copper supplementation (e.g., 1-2 mg/day) may be necessary, and copper levels should be monitored.

- Medication Interactions:

- Antibiotics: Zinc can interfere with the absorption of quinolone and tetracycline antibiotics. Take zinc at least 2 hours before or 4-6 hours after these antibiotics.

- Diuretics: Thiazide diuretics can increase urinary zinc excretion.

- Penicillamine: Used for Wilson's disease and rheumatoid arthritis; zinc can reduce its absorption.

- Gastrointestinal Upset: Some individuals may experience nausea or stomach upset, especially with zinc sulfate or when taken on an empty stomach. Taking zinc with food can help mitigate this.

Actionable Advice for Maintaining Optimal Zinc Levels

Maintaining optimal zinc levels is crucial for long-term health. Here's actionable advice:

- Prioritize a Balanced, Zinc-Rich Diet: Incorporate a variety of zinc-rich foods, particularly from animal sources if applicable. For vegetarians/vegans, pay close attention to legumes, nuts, seeds, and whole grains, and use preparation methods that reduce phytates.

- Be Aware of Deficiency Symptoms: If you experience persistent symptoms like frequent infections, slow wound healing, hair loss, or changes in taste/smell, consult your healthcare provider.

- Avoid Excessive Supplementation: Do not routinely take high-dose zinc supplements unless specifically advised by a medical professional. Stick to the RDA or a multivitamin providing a modest amount of zinc.

- Consult a Healthcare Professional for Testing and Supplementation: If you suspect a deficiency or are considering zinc supplementation, especially at therapeutic doses, get a blood test and discuss your options with a doctor or registered dietitian. They can provide personalized advice based on your individual health status, diet, and any medications you are taking.

- Monitor for Toxicity Symptoms: If you are on high-dose zinc, be vigilant for symptoms of toxicity, particularly gastrointestinal distress or signs of copper deficiency (e.g., fatigue, neurological symptoms).

In conclusion, zinc is an indispensable micronutrient that underpins a vast array of physiological functions. Both deficiency and toxicity can have significant, sometimes severe, health consequences. The zinc blood test is a valuable tool for assessing zinc status, but its interpretation requires a comprehensive understanding of influencing factors and clinical context. By focusing on a balanced, zinc-rich diet, being mindful of supplementation, and consulting healthcare professionals, individuals can effectively maintain optimal zinc levels and support their overall health.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of abnormal Zinc levels?

The most common cause of abnormal zinc levels is inadequate dietary intake, leading to deficiency. This is particularly prevalent in populations with limited access to zinc-rich foods or those relying heavily on plant-based diets high in phytates without proper preparation techniques. Malabsorption syndromes, chronic diseases, and increased physiological demands (like pregnancy) also contribute significantly to deficiency. On the other hand, abnormally high zinc levels (toxicity) are almost exclusively caused by excessive intake from dietary supplements, often exceeding the Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) of 40 mg/day for adults. It is rare to achieve toxic levels through diet alone.

How often should I get my Zinc tested?

For most healthy individuals without symptoms of deficiency or toxicity, routine zinc testing is not typically necessary. However, testing is recommended if:

- You exhibit symptoms suggestive of zinc deficiency (e.g., frequent infections, slow wound healing, hair loss, unexplained weight loss, altered taste/smell).

- You have medical conditions that increase your risk of deficiency (e.g., malabsorption syndromes, chronic kidney disease, alcoholism, inflammatory bowel disease).

- You follow a restrictive diet (e.g., long-term vegetarian or vegan) and are concerned about your intake.

- You are taking high-dose zinc supplements (over 40 mg/day) for an extended period, in which case monitoring zinc and copper levels may be advised by your doctor to prevent toxicity.

- You are undergoing treatment for a diagnosed zinc deficiency, in which case your doctor will recommend follow-up tests to monitor treatment effectiveness. The frequency of testing for at-risk individuals or those undergoing treatment will be determined by a healthcare professional based on their clinical judgment.

Can lifestyle changes improve my Zinc levels?

Yes, lifestyle changes can significantly improve zinc levels, primarily by optimizing dietary intake and addressing factors that impair absorption or increase loss. Key strategies include:

- Dietary Modification: Incorporating more zinc-rich foods, particularly oysters, red meat, poultry, and certain seafood. For plant-based diets, focus on legumes, nuts, seeds, and whole grains, and employ preparation methods like soaking, sprouting, and fermentation to reduce phytate content and enhance absorption.

- Addressing Malabsorption: If an underlying medical condition like celiac disease or Crohn's disease is causing malabsorption, managing that condition effectively will improve nutrient absorption, including zinc.

- Limiting Alcohol Intake: Chronic alcohol consumption impairs zinc absorption and increases its excretion, so reducing or eliminating alcohol can help normalize zinc levels.

- Managing Medications: Discuss with your doctor if any medications you are taking might be affecting your zinc levels. Adjustments or timing changes (e.g., separating zinc supplements from certain antibiotics) might be recommended.

- Balanced Nutrition: Ensuring a generally balanced diet rich in diverse nutrients supports overall metabolic health, indirectly benefiting zinc status by providing co-factors and improving gut health. These lifestyle adjustments, especially dietary changes, are often the first line of defense against zinc deficiency and can be highly effective in maintaining optimal levels.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Always consult a healthcare professional.