Folate Deficiency Anemia: Symptoms and Causes

Introduction

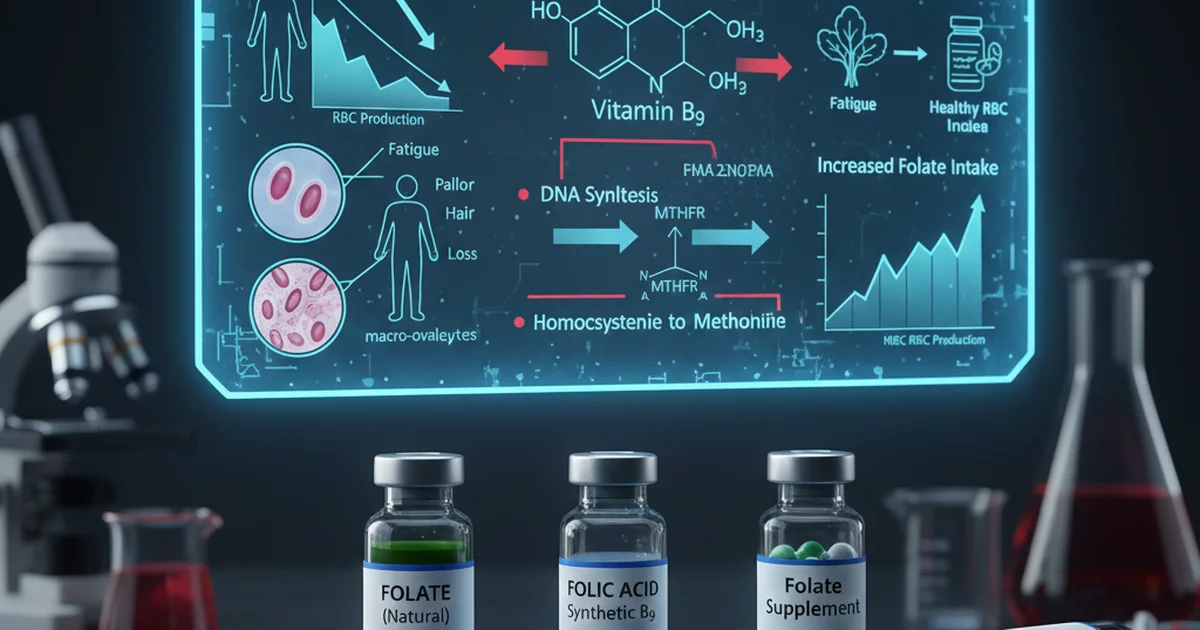

Folate, also known as vitamin B9, is a water‑soluble B‑vitamin that plays a pivotal role in one‑carbon metabolism, DNA synthesis, and the methylation of homocysteine to methionine. When folate stores become insufficient, rapidly dividing cells—particularly those in the bone marrow—cannot produce adequate DNA, leading to the production of abnormally large, immature red blood cells (macro‑ovalocytes). This manifests clinically as folate deficiency anemia, a reversible form of macrocytic anemia that may coexist with other nutrient deficiencies. Understanding the symptoms, underlying causes, and ways to correct folate insufficiency is essential for clinicians, dietitians, and anyone interested in optimal health.

Folate Physiology: Why It Matters

Key Functions

- DNA synthesis & repair – Folate provides methyl groups for thymidine production, a building block of DNA.

- Amino‑acid metabolism – Converts homocysteine to methionine, reducing cardiovascular risk.

- Red blood cell maturation – Enables proper nuclear maturation of erythroid precursors.

Forms of Folate

| Form | Description | Clinical relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Folic acid | Synthetic, fully oxidized, used in fortified foods and supplements. | Highly stable, but requires reduction to become active. |

| 5‑Methyltetrahydrofolate (5‑MTHF) | Predominant circulating form; the biologically active methyl donor. | Directly usable, bypasses dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) step. |

| Dietary folates | Polyglutamated forms in foods; must be deconjugated by intestinal enzymes. | Determines bioavailability from natural sources. |

Folate Deficiency Anemia: Pathophysiology

- Insufficient intracellular folate → impaired synthesis of thymidine → defective DNA replication.

- Nuclear-cytoplasmic asynchrony in erythroblasts → cells enlarge (macrocytosis) but cannot divide normally.

- Premature release of megaloblasts into circulation → macro‑ovalocytes with reduced hemoglobin content (macrocytic, megaloblastic anemia).

- Secondary effects – Elevated homocysteine, impaired immune function, and neurologic changes when folate deficiency co‑exists with vitamin B12 deficiency.

Clinical Presentation: Symptoms

Hematologic Signs

- Fatigue, weakness, and pallor – Result of reduced oxygen‑carrying capacity.

- Dyspnea on exertion – Due to tissue hypoxia.

- Tachycardia – Compensatory response to anemia.

Non‑Hematologic Manifestations

- Glossitis (smooth, beefy‑red tongue) and mouth ulcers.

- Pernicious‑type dermatitis – Hyperpigmented, scaly skin lesions.

- Neurocognitive changes – Difficulty concentrating, irritability; severe deficiency may mimic B12 neuropathy when combined.

- Gastrointestinal disturbances – Nausea, loss of appetite.

Note: Symptoms often overlap with other macrocytic anemias; a thorough work‑up is required to isolate folate deficiency.

Primary Causes of Folate Deficiency

1. Inadequate Dietary Intake

- Low consumption of leafy greens, legumes, and fortified grains.

- Strict low‑carb or “clean‑eating” trends that exclude fortified cereals.

2. Malabsorption

- Celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, or bariatric surgery → reduced absorption in the proximal small intestine.

- Chronic alcohol use – Impairs folate transport and hepatic storage.

3. Increased Physiologic Demand

- Pregnancy & lactation – Fetal growth and milk production dramatically raise folate requirements.

- Hemolytic anemia or rapid cell turnover (e.g., psoriasis).

4. Medications Interfering with Folate Metabolism

- Antimetabolites (methotrexate, trimethoprim) – Directly inhibit dihydrofolate reductase.

- Anticonvulsants (phenytoin, carbamazepine) – Increase renal folate loss.

- Sulfonamides – Compete for folate pathways.

5. Genetic Variants

- MTHFR polymorphisms (C677T, A1298C) reduce conversion of folic acid to 5‑MTHF, potentially lowering functional folate status.

Who Is Most at Risk?

| Population | Why Risk Is Elevated |

|---|---|

| Women of childbearing age | Higher dietary needs; many unplanned pregnancies. |

| Elderly | Decreased gastric acid, polypharmacy, and malnutrition. |

| Alcohol-dependent individuals | Poor intake + impaired hepatic storage. |

| Patients with gastrointestinal disorders | Malabsorption of folate from diet. |

| Individuals on chronic anticonvulsant or methotrexate therapy | Drug‑induced folate depletion. |

Diagnosis and Reference Ranges

Laboratory evaluation typically includes serum/plasma folate (reflects recent intake) and red blood cell (RBC) folate (reflects tissue stores).

Reference Ranges Table

| Population | Test | Normal Range | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Men | Serum folate | 5–15 | ng/mL | Reflects recent dietary intake |

| Adult Women | Serum folate | 5–15 | ng/mL | Slightly lower in premenopausal women |

| Children (1–12 yr) | Serum folate | 4–12 | ng/mL | Age‑dependent; lower in toddlers |

| Pregnant Women | Serum folate | 6–18 | ng/mL | Increased demand; target > 7 ng/mL |

| All Ages | RBC folate | 140–628 | ng/mL | Indicates long‑term stores; > 140 ng/mL considered sufficient |

| Elderly (> 65 yr) | RBC folate | 140–600 | ng/mL | Adjusted for decreased absorption |

Interpretation:

- Serum folate < 5 ng/mL suggests recent inadequate intake or acute depletion.

- RBC folate < 140 ng/mL is diagnostic of folate deficiency anemia when accompanied by macrocytosis.

Dietary Sources and Bioavailability

Natural Food Sources

| Food Category | Typical Folate Content (µg per serving) | Bioavailability |

|---|---|---|

| Dark leafy greens (spinach, kale) | 50–100 | 50–60 % (polyglutamate hydrolysis required) |

| Legumes (lentils, chickpeas) | 180–200 | 40–50 % |

| Asparagus, Brussels sprouts | 80–100 | 50 % |

| Citrus fruits (orange, grapefruit) | 30–50 | 70 % (free folate) |

| Avocado | 80 | 60 % |

| Fortified breakfast cereals | 100–400 | 85–100 % (synthetic folic acid) |

| Enriched wheat flour (bread, pasta) | 140–160 | 85–100 % |

Key point: Synthetic folic acid added to fortified foods is far more bioavailable than natural food folates because it is already in the monoglutamate form and does not require intestinal deconjugation.

Factors Influencing Bioavailability

- Cooking losses: Heat destroys up to 30 % of folate; steaming preserves more than boiling.

- Alcohol consumption: Reduces hepatic uptake and increases urinary excretion.

- Gut microbiota: Certain bacteria synthesize folate, contributing modestly to systemic levels.

Supplementation Strategies

When to Supplement

- Documented deficiency (serum < 5 ng/mL or RBC < 140 ng/mL).

- High‑risk groups (pregnancy, malabsorption, chronic methotrexate therapy).

- Situations where diet alone cannot meet requirements (e.g., severe restrictive diets).

Recommended Dosages

| Situation | Daily Dose | Form | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| General adult maintenance | 400 µg (0.4 mg) | Folic acid or 5‑MTHF | Matches RDA for most adults |

| Pregnancy | 600–800 µg (0.6–0.8 mg) | Folic acid (preferably) | Prevents neural‑tube defects |

| Therapeutic repletion (deficiency anemia) | 1–5 mg (1000–5000 µg) | Folic acid, divided doses | Continue for 4–6 weeks, then reassess |

| Methotrexate therapy | 1–5 mg daily (folic acid) | Folic acid | Reduces toxicity without compromising efficacy |

| MTHFR polymorphism | 1–5 mg (5‑MTHF) | 5‑MTHF | Bypasses DHFR step; may be better tolerated |

Administration tips:

- Take folic acid on an empty stomach for maximal absorption, though food does not markedly impede uptake.

- For patients on antacids or proton‑pump inhibitors, consider 5‑MTHF because it does not rely on gastric acidity for activation.

Monitoring

- Re‑measure RBC folate after 8–12 weeks of supplementation.

- Ensure serum homocysteine normalizes, indicating functional folate adequacy.

Interactions, Contraindications, and Safety

- Vitamin B12 deficiency can be masked by high folic acid intake; always assess B12 status before high‑dose folic acid therapy.

- Anticonvulsants may increase folate requirements; supplement concurrently to avoid seizure breakthrough.

- Renal impairment: No dose adjustment needed, but monitor for accumulation of unmetabolized folic acid in extreme cases.

- Allergic reactions to folic acid are rare but possible; switch to 5‑MTHF if hypersensitivity occurs.

Upper intake level: 1 mg (1000 µg) per day is generally considered safe for the general population; higher therapeutic doses are tolerated under medical supervision.

Practical, Actionable Advice

- Screen high‑risk individuals (pregnant women, alcohol users, patients on methotrexate) with a serum folate test at least once per year.

- Incorporate at least one folate‑rich food into each main meal:

- Breakfast: fortified cereal with low‑fat milk.

- Lunch: mixed bean salad with leafy greens and citrus dressing.

- Dinner: stir‑fried kale with tofu and brown rice.

- Limit cooking losses by steaming vegetables for ≤ 5 minutes and using cooking water in soups or sauces.

- Avoid excessive alcohol (> 2 drinks/day) to protect hepatic folate stores.

- If on medications known to deplete folate, discuss prophylactic supplementation with your healthcare provider.

- For women planning pregnancy, start a daily 400–800 µg folic acid supplement at least one month before conception and continue through the first trimester.

- Re‑evaluate after 3 months of supplementation; if RBC folate remains low, increase dose or assess for malabsorption.

Summary

Folate deficiency anemia is a preventable and reversible condition that stems from inadequate intake, malabsorption, increased physiological demand, medication interference, or genetic factors. The hallmark clinical picture includes macrocytic anemia, glossitis, and sometimes neurocognitive changes. Diagnosis relies on serum and RBC folate measurements, with clear reference ranges guiding interpretation. Dietary sources—particularly fortified grains and leafy vegetables—provide the bulk of daily folate, but bioavailability varies widely. When diet alone is insufficient, targeted supplementation (400 µg–5 mg daily, depending on need) restores stores, normalizes blood counts, and mitigates associated risks such as neural‑tube defects in pregnancy. Ongoing monitoring, attention to drug‑nutrient interactions, and lifestyle modifications are essential components of comprehensive management.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of abnormal Folate (Vitamin B9) levels?

The most frequent cause of low folate is inadequate dietary intake, often compounded by poor absorption due to chronic alcohol use or gastrointestinal disorders. In many developed countries, fortified foods have reduced the prevalence of pure dietary deficiency, so clinicians now more commonly encounter low folate secondary to medication use (e.g., methotrexate, anticonvulsants) or increased physiological demand during pregnancy.

How often should I get my Folate (Vitamin B9) tested?

For average healthy adults, a folate test is not required routinely. However, testing is advised:

- Every 12 months for pregnant women, individuals with malabsorptive conditions, or those on folate‑depleting medications.

- Every 6–12 months for patients with a history of folate deficiency anemia or chronic alcoholism.

- Prior to initiating high‑dose methotrexate or long‑term anticonvulsant therapy, to establish a baseline and guide supplementation.

Can lifestyle changes improve my Folate (Vitamin B9) levels?

Absolutely. Optimizing diet by including folate‑rich foods (leafy greens, legumes, fortified cereals) and minimizing cooking losses can raise serum folate within weeks. Reducing alcohol consumption restores hepatic storage capacity, while addressing gastrointestinal health (treating celiac disease, optimizing gut flora) enhances absorption. Regular physical activity improves overall metabolism, and maintaining a balanced, varied diet ensures adequate intake of folate‑cooperating nutrients such as vitamin B12, B6, and riboflavin.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Always consult a healthcare professional.