Folic Acid vs. Folate: What’s the Difference?

Introduction

Vitamin B9, commonly known as folate when it occurs naturally in foods and as folic acid when it is synthetically manufactured, plays a pivotal role in DNA synthesis, red‑blood‑cell formation, and the metabolism of homocysteine. Because the terms are often used interchangeably, many people are confused about whether they are receiving the “right” form of the vitamin, how much they need, and which foods or supplements are most effective. This article unpacks the biochemical distinctions, compares dietary sources, examines bioavailability, and offers practical guidance for achieving optimal B9 status through diet and supplementation.

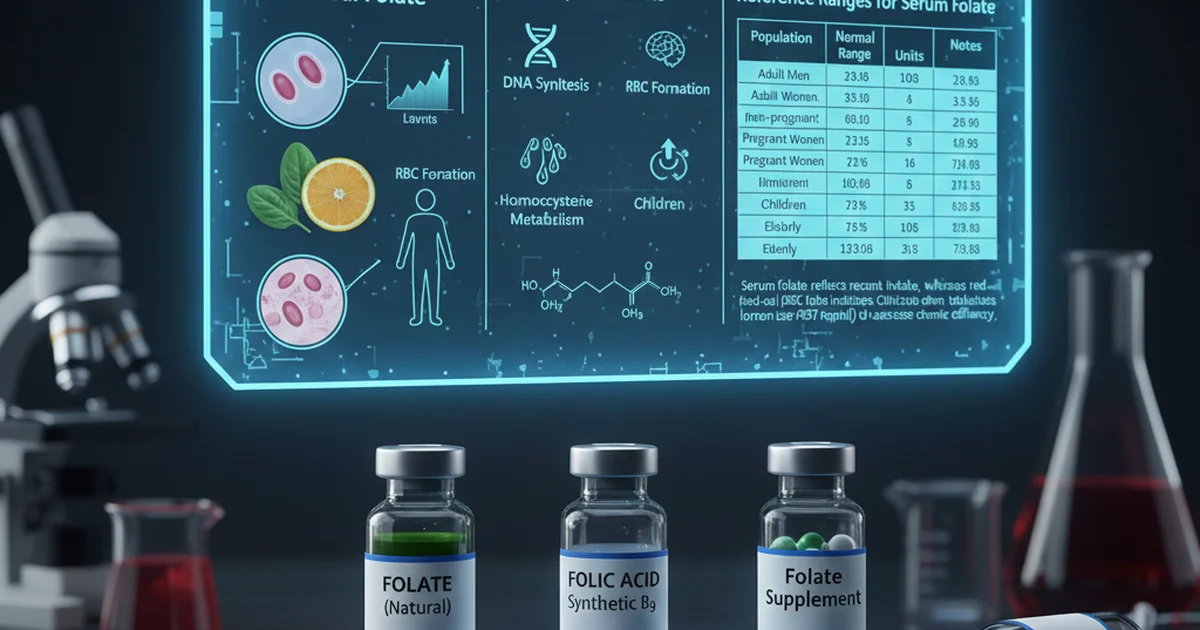

Reference Ranges for Serum Folate

| Population | Normal Range | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Men | 5–20 | ng/mL | Values reflect fasting serum; higher levels may indicate recent supplementation |

| Adult Women (non‑pregnant) | 5–20 | ng/mL | Lower end common in women with poor dietary intake |

| Pregnant Women | 7–25 | ng/mL | Increased requirement for fetal development |

| Children (1–12 yr) | 3–15 | ng/mL | Age‑dependent; infants have higher needs relative to body weight |

| Elderly (≥65 yr) | 4–18 | ng/mL | Absorption may decline with age, making monitoring useful |

Serum folate reflects recent intake, whereas red‑blood‑cell (RBC) folate indicates longer‑term stores. Clinicians often use RBC folate (> 317 ng/mL) to assess chronic deficiency.

1. Chemical Distinctions

Folate (Natural Form)

- Structure: A polyglutamate chain attached to a p‑aminobenzoic acid (PABA) moiety.

- Sources: Leafy greens, legumes, citrus fruits, and liver.

- Metabolism: Requires intestinal brush‑border enzymes (folate‑converting enzymes) to cleave polyglutamate chains into monoglutamate forms before absorption.

Folic Acid (Synthetic Form)

- Structure: A monoglutamate, fully oxidized compound that is chemically stable.

- Sources: Fortified grains, prenatal vitamins, and many over‑the‑counter B‑complex supplements.

- Metabolism: Directly absorbed via passive diffusion; does not need enzymatic de‑conjugation. However, it must be reduced by dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) to become biologically active tetrahydrofolate (THF).

Key Difference: The body must convert folic acid into the active reduced form, a step that can become saturated at high intakes, leading to unmetabolized folic acid in the bloodstream. Natural folate is already in a reduced, polyglutamate state that the gut processes more efficiently.

2. Dietary Sources and Their Folate Content

| Food Group | Representative Foods | Approximate Folate (µg DFE) per Serving |

|---|---|---|

| Dark Leafy Greens | Spinach (1 cup cooked), Kale (1 cup raw) | 120–140 |

| Legumes | Lentils (½ cup cooked), Chickpeas (½ cup) | 180–200 |

| Cruciferous Vegetables | Broccoli (1 cup cooked), Brussels sprouts (½ cup) | 60–80 |

| Citrus & Berries | Orange (1 medium), Strawberries (½ cup) | 30–50 |

| Whole Grains (fortified) | Enriched wheat bread (2 slices) | 140 |

| Animal Products | Liver (3 oz), Egg yolk (1 large) | 200 (liver), 20 (egg) |

DFE = Dietary Folate Equivalents. One µg DFE equals 1 µg natural folate or 0.6 µg folic acid from fortified foods or supplements.

Practical Tips

- Combine foods: Pairing a folate‑rich vegetable with a source of vitamin C (e.g., bell peppers with orange slices) can improve folate stability during cooking.

- Cooking method matters: Steaming or microwaving preserves more folate than boiling, which can leach the water‑soluble vitamin.

- Avoid excess heat: Prolonged high‑temperature cooking degrades up to 50 % of folate content.

3. Bioavailability: Folate vs. Folic Acid

Natural Folate

- Absorption Rate: Approximately 50 % of dietary folate is absorbed under normal conditions.

- Factors Reducing Absorption: Alcohol intake, certain medications (e.g., phenytoin, sulfasalazine), and genetic polymorphisms in the MTHFR enzyme can lower conversion efficiency.

Synthetic Folic Acid

- Absorption Rate: Up to 85 % when taken on an empty stomach due to passive diffusion.

- Saturation Point: DHFR activity becomes limiting above ~200 µg per dose; excess remains unmetabolized, which some studies suggest may interfere with natural folate metabolism and mask B12 deficiency.

Bottom Line: For most healthy adults, fortified folic acid provides a reliable way to meet the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA). However, individuals with compromised DHFR activity, certain genetic variants, or those who consume large fortified doses should consider natural folate sources or methylated forms (e.g., 5‑MTHF) to avoid potential excess unmetabolized folic acid.

4. Recommended Intakes

| Life Stage | RDA (µg DFE) | Upper Intake Level (UL) |

|---|---|---|

| Infants 0–6 mo | 65 | — |

| Children 1–3 yr | 150 | 300 |

| Children 4–8 yr | 200 | 400 |

| Adolescents 9–13 yr | 300 | 600 |

| Teens 14–18 yr | 400 | 800 |

| Adults (19 + yr) | 400 | 1000 |

| Pregnant women | 600 | 1000 |

| Lactating women | 500 | 1000 |

Critical Note: The UL of 1 mg (1000 µg) applies to synthetic folic acid from fortified foods and supplements only; natural folate from foods does not have an established UL because it is less likely to cause adverse effects.

5. Supplementation Strategies

When to Consider Supplements

- Pregnancy or planning pregnancy – to prevent neural‑tube defects.

- Diagnosed deficiency – confirmed by low serum or RBC folate.

- Malabsorption conditions – celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, or after bariatric surgery.

- Medications that interfere with folate metabolism – e.g., methotrexate, trimethoprim, or anticonvulsants.

Choosing the Right Form

| Form | Typical Dose (µg DFE) | Advantages | Situations Best Suited |

|---|---|---|---|

| Folic Acid (synthetic) | 400–800 | High bioavailability, inexpensive | General supplementation, prenatal vitamins |

| 5‑MTHF (L‑methylfolate) | 400–800 | Bypasses MTHFR conversion, minimal unmetabolized folic acid | MTHFR polymorphisms, psychiatric meds (e.g., SSRIs) |

| Folinic Acid (Leucovorin) | 100–400 | Directly usable, used to rescue methotrexate toxicity | Cancer therapy adjunct, certain genetic issues |

Actionable Advice

- Start with food first – Aim for at least 3–4 servings of folate‑rich foods daily.

- Add a prenatal‑grade supplement (400 µg folic acid) for women of childbearing age.

- If you have an MTHFR variant (C677T or A1298C), discuss switching to 5‑MTHF with your clinician.

- Monitor levels – Repeat serum folate testing after 8–12 weeks of supplementation to confirm adequacy.

6. Interactions and Safety Considerations

- Vitamin B12 Masking: High folic acid intake can correct anemia caused by B12 deficiency while neurological damage continues. Therefore, always assess B12 status before initiating high‑dose folic acid.

- Antifolate Drugs: Methotrexate, trimethoprim, sulfasalazine, and certain antiretrovirals inhibit folate metabolism. Supplemental folic acid (or folinic acid) is often prescribed to mitigate side effects.

- Alcohol: Chronic consumption impairs folate absorption and increases urinary excretion, heightening deficiency risk.

- Pregnancy: Excessive folic acid (> 1 mg/day) has not shown additional benefit and may be associated with increased risk of certain allergies in offspring; stay within the UL.

7. Practical Meal Planning

| Meal | Components | Approx. Folate (µg DFE) |

|---|---|---|

| Breakfast | Whole‑grain fortified toast (2 slices) + orange juice (1 cup) | 260 |

| Snack | Handful of almonds + strawberry (½ cup) | 45 |

| Lunch | Spinach salad with chickpeas, cherry tomatoes, and lemon vinaigrette | 300 |

| Afternoon Snack | Greek yogurt (plain) with a drizzle of honey | 15 |

| Dinner | Grilled salmon, quinoa, and steamed broccoli | 120 |

| Total | — | ~ 740 µg DFE |

Tip: If total intake falls below the RDA, add a 400 µg folic acid supplement (e.g., prenatal vitamin) to bridge the gap.

8. Special Populations

Pregnant Women

- Increased Demand: Folate is critical for neural‑tube closure (by week 4) and rapid fetal cell division.

- Supplementation Recommendation: 400–800 µg folic acid daily before conception and through the first trimester.

Elderly

- Absorption Decline: Reduced activity of intestinal folate‑converting enzymes and possible polypharmacy.

- Action: Regular dietary assessments and, if needed, low‑dose folic acid (200–400 µg) to maintain RBC folate > 317 ng/mL.

Individuals with MTHFR Polymorphisms

- Problem: Decreased conversion of folic acid to active THF.

- Solution: Use 5‑MTHF supplements (400 µg) or increase intake of natural folate‑rich foods.

9. Monitoring and Follow‑Up

- Initial Test: Serum folate (fasting) gives a snapshot of recent intake; RBC folate provides a 3‑month view.

- Frequency: For high‑risk groups (pregnant, malabsorption, on antifolate drugs), test every 3–6 months. For the general population, testing every 2–3 years or when symptoms arise (e.g., macrocytic anemia, glossitis).

- Interpretation:

- Serum < 5 ng/mL → acute deficiency, likely dietary.

- RBC < 317 ng/mL → chronic deficiency, consider supplementation.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of abnormal Folate (Vitamin B9) levels?

The leading cause of low folate is inadequate dietary intake, especially in populations that consume few fruits, vegetables, or fortified grains. Secondary contributors include chronic alcohol use, malabsorption syndromes (e.g., celiac disease), and medications that interfere with folate metabolism such as methotrexate or certain anticonvulsants. Elevated serum folate is most often seen in individuals taking high‑dose folic acid supplements or consuming heavily fortified foods.

How often should I get my Folate (Vitamin B9) tested?

For healthy adults without risk factors, testing every 2–3 years is sufficient. Pregnant women, people with malabsorption disorders, those on antifolate medications, or individuals with known MTHFR variants should have serum and/or RBC folate checked every 3–6 months or as directed by their healthcare provider. If you experience symptoms of deficiency (e.g., fatigue, glossitis, macrocytic anemia), testing should be performed promptly.

Can lifestyle changes improve my Folate (Vitamin B9) levels?

Absolutely. Increasing consumption of folate‑rich foods (leafy greens, legumes, citrus fruits) and reducing alcohol intake are the most effective strategies. Cooking methods that preserve folate—such as steaming or microwaving—help maintain nutrient content. Additionally, regular physical activity improves overall gut health, which can enhance nutrient absorption. For those with genetic or medication‑related impediments, switching to methylated folate supplements (5‑MTHF) may provide a more bioavailable source.

Takeaway: Understanding the distinction between folate and folic acid empowers you to make informed dietary and supplement choices. By prioritizing natural food sources, selecting the appropriate supplement form, and monitoring levels when needed, you can maintain optimal B9 status for cellular health, pregnancy outcomes, and overall well‑being.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Always consult a healthcare professional.