High Folate Levels: Potential Risks Explained

Folate, also known as vitamin B9, is a water‑soluble vitamin that plays a central role in DNA synthesis, amino‑acid metabolism, and methylation reactions. While adequate folate is essential for normal growth and development, excessively high serum or red‑cell folate concentrations can carry health risks. This article provides an evidence‑based overview of folate’s dietary sources, bioavailability, supplementation practices, normal laboratory ranges, and the potential adverse effects of unusually high levels. Actionable strategies for maintaining optimal folate status are also included.

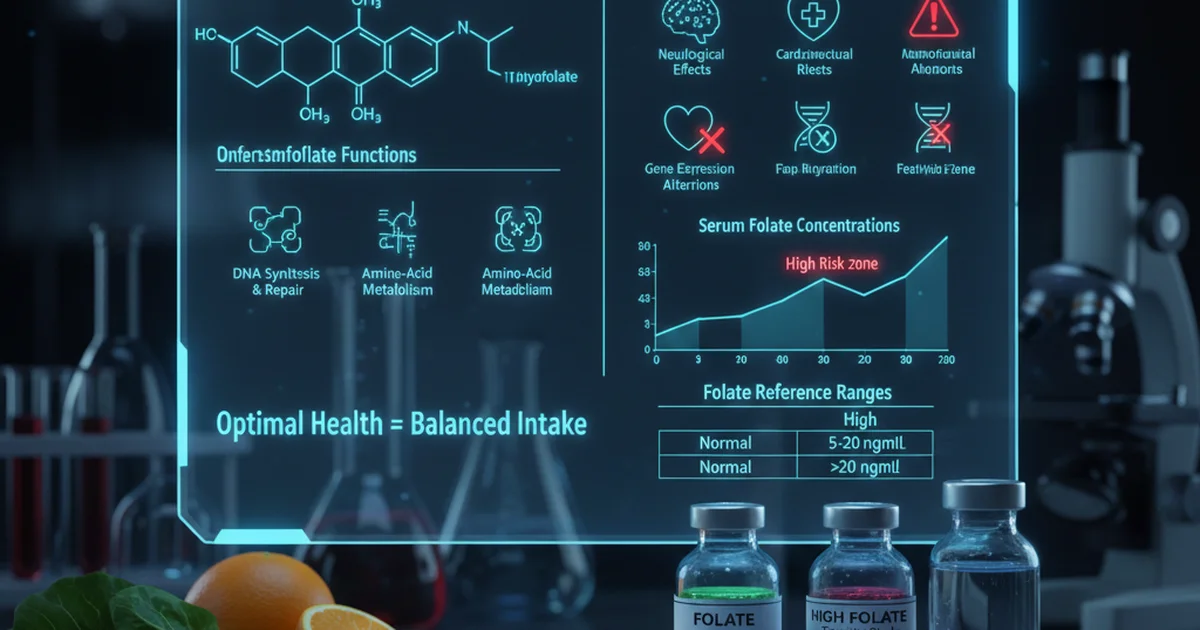

Understanding Folate and Its Biological Functions

- DNA synthesis & repair – Folate supplies one‑carbon units needed for thymidine and purine production.

- Amino‑acid metabolism – Converts homocysteine to methionine, helping to regulate plasma homocysteine concentrations.

- Methylation – Supports the methylation of DNA, proteins, and neurotransmitters, influencing gene expression and neurological health.

Because folate is water‑soluble, the body stores relatively little; regular intake through diet or supplements is required to sustain adequate tissue levels.

Dietary Sources of Folate

| Food Group | Typical Folate Content (µg per serving) | Notes on Preparation |

|---|---|---|

| Dark leafy greens (spinach, kale, collard greens) | 60–100 | Raw or lightly cooked preserves most folate; prolonged boiling can cause losses. |

| Legumes (lentils, chickpeas, black beans) | 150–200 | Soaking and cooking retain high levels; canned varieties may have added sodium. |

| Citrus fruits (orange, grapefruit) | 30–50 | Vitamin C enhances folate absorption. |

| Avocado | 80–100 | Provides healthy fats that aid overall nutrient absorption. |

| Fortified grains (bread, breakfast cereals) | 100–400 (depends on fortification level) | Synthetic folic acid is more stable and has higher bioavailability than natural folate. |

| Nuts & seeds (sunflower seeds, peanuts) | 30–50 | Good snack option, but portion size matters for calorie control. |

| Asparagus, Brussels sprouts, broccoli | 70–100 | High‑fiber vegetables that also contribute antioxidants. |

Key takeaway: Whole foods deliver natural folate (tetrahydrofolate forms) while fortified products supply synthetic folic acid, which is absorbed more efficiently but can contribute to higher serum levels when consumed in excess.

Bioavailability: Natural Folate vs. Synthetic Folic Acid

- Natural folate (found in foods) is typically 50–60 % as bioavailable as synthetic folic acid because it exists in multiple polyglutamate forms that must be deconjugated in the intestine.

- Folic acid (the synthetic form used in supplements and fortification) is ~85 % bioavailable when taken with food and ~100 % on an empty stomach.

- L‑methylfolate, the biologically active form, bypasses the reduction step required for folic acid, offering near‑complete bioavailability and is preferred for individuals with certain genetic polymorphisms (e.g., MTHFR variants).

Understanding these differences helps clinicians and consumers gauge how much folate actually reaches systemic circulation.

Recommended Intake and Supplementation

| Life Stage | Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) | Upper Intake Level (UL) |

|---|---|---|

| Adults (both sexes) | 400 µg dietary folate equivalents (DFE) per day | 1 000 µg DFE per day (from supplements/fortified foods) |

| Pregnancy | 600 µg DFE per day | 1 000 µg DFE per day |

| Lactation | 500 µg DFE per day | 1 000 µg DFE per day |

| Children (9–13 y) | 300 µg DFE per day | 800 µg DFE per day |

- Dietary folate equivalents (DFE) adjust for the higher bioavailability of folic acid (+1.7 µg per µg folic acid).

- The UL primarily addresses synthetic folic acid from fortified foods and supplements; natural food folate rarely reaches toxic levels.

Supplementation guidelines

- Use a single‑dose supplement (400–800 µg) for most adults unless a specific medical condition warrants higher dosing (e.g., certain anemias).

- Pregnant women should follow prenatal formulations that contain 400–800 µg folic acid in addition to dietary intake, aiming to meet the RDA without exceeding the UL.

- Individuals with renal impairment or those on antiepileptic drugs may require close monitoring, as drug interactions can alter folate metabolism.

Laboratory Assessment and Reference Ranges

Testing can be performed as serum folate (reflects recent intake) or red‑cell folate (reflects longer‑term status). Below is a consolidated reference table commonly used in clinical practice.

| Population | Normal Range (Serum) | Normal Range (Red‑Cell) | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Men | 5–20 | 200–800 | ng/mL (serum) / ng/mL (RBC) | Values may vary by assay; fasting sample recommended |

| Adult Women | 5–20 | 200–800 | ng/mL / ng/mL | Lower limits may be slightly higher in pregnancy |

| Pregnant Women | 5–25 | 250–900 | ng/mL / ng/mL | Increased demand; red‑cell values more informative |

| Children (1–12 y) | 4–15 | 150–600 | ng/mL / ng/mL | Age‑dependent; infants have higher turnover |

| Elderly (≥65 y) | 5–18 | 180–750 | ng/mL / ng/mL | Monitor for concurrent B12 deficiency |

Interpretation tip: Serum folate > 20 ng/mL or red‑cell folate > 900 ng/mL typically indicates excessive intake, especially when dietary history includes high‑dose supplements or heavily fortified foods.

Causes of Elevated Folate Levels

- High‑dose supplementation – Regular intake of > 1 000 µg folic acid from tablets, multivitamins, or prenatal formulas.

- Excessive consumption of fortified foods – Frequent intake of fortified cereals, breads, and snack bars can cumulatively exceed the UL.

- Genetic variations – Certain polymorphisms (e.g., MTHFR C677T homozygosity) reduce conversion efficiency, prompting clinicians to prescribe higher doses of L‑methylfolate, which can raise serum levels.

- Renal insufficiency – Impaired clearance may cause accumulation of folic acid metabolites.

- Laboratory artifact – Recent high‑folate meals can transiently elevate serum folate; confirm with red‑cell measurement if persistent elevation is suspected.

Potential Risks of High Folate Levels

1. Masking Vitamin B12 Deficiency

- Mechanism: Folate can correct the megaloblastic anemia caused by B12 deficiency without addressing neurological damage.

- Clinical consequence: Patients may develop irreversible neuropathy while appearing hematologically normal.

- Risk groups: Elderly individuals, vegans, and patients on long‑term proton‑pump inhibitors are especially vulnerable.

Action: When high folate is detected, always assess serum B12, methylmalonic acid, and homocysteine to rule out covert B12 deficiency.

2. Potential Cancer Promotion

- Evidence summary: Some epidemiological studies suggest that very high folic acid intake (> 1 000 µg/day) may accelerate the growth of pre‑existing neoplastic lesions, particularly in the colorectum and prostate.

- Biologic rationale: Folate fuels DNA synthesis; excess supply could aid rapidly dividing malignant cells.

- Practical implication: Individuals with a personal or strong family history of colorectal cancer should avoid chronic high‑dose folic acid supplementation unless medically indicated.

3. Interaction with Anticonvulsant Medications

- Drugs affected: Phenytoin, carbamazepine, and valproic acid can interfere with folate metabolism, sometimes prompting clinicians to prescribe high folate doses.

- Risk: Overcorrection may lead to hyperfolatemia, which can further alter drug plasma levels and increase toxicity.

4. Possible Immune Dysregulation

- Preliminary data indicate that supraphysiologic folate may modulate cytokine profiles, potentially influencing autoimmune disease activity. The clinical relevance remains uncertain, but caution is advised for patients with active autoimmune conditions.

5. Metabolic Overload in Renal Disease

- The kidneys excrete folic acid metabolites; impaired renal function can cause accumulation, leading to folate toxicity manifested by gastrointestinal upset, skin rash, and, rarely, seizures.

Who Is Most Susceptible to Folate Overload?

| Group | Why They’re At Risk | Recommended Monitoring |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnant women taking multiple prenatal products | Double counting of folic acid from separate supplements | Serum folate each trimester if taking > 800 µg/day |

| Elderly on B12 supplementation alone | Masking of B12 deficiency | Combined B12 and folate panel annually |

| Individuals on high‑dose L‑methylfolate for psychiatric conditions | Prescription doses often exceed 1 000 µg | Periodic red‑cell folate measurement |

| Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) | Reduced clearance of folic acid | Quarterly labs, adjust supplement dose |

| Vegans using fortified meal replacements | Frequent consumption of fortified breads and bars | Check serum folate after 3 months of regimen |

Practical Guidance for Maintaining Optimal Folate Status

Dietary Strategies

- Prioritize whole‑food sources (leafy greens, legumes, citrus) to obtain natural folate without excessive synthetic intake.

- Limit reliance on fortified foods if you already take a supplement; read nutrition labels for folic acid content.

- Pair folate‑rich foods with vitamin C (e.g., orange slices with spinach salad) to enhance absorption.

Supplementation Best Practices

- Assess baseline status – Obtain serum and red‑cell folate before initiating high‑dose supplements.

- Choose the appropriate form – L‑methylfolate for individuals with MTHFR variants; standard folic acid for general prevention.

- Stay within the UL – Do not exceed 1 000 µg DFE from combined dietary and supplemental sources unless directed by a healthcare professional.

- Monitor regularly – Repeat testing after 8–12 weeks of any dose change.

Lifestyle Adjustments

- Avoid excessive alcohol – Alcohol interferes with folate absorption and utilization.

- Maintain adequate B12 intake – Include animal products, fortified plant milks, or a B12 supplement.

- Stay hydrated – Adequate water intake supports renal excretion of excess folic acid.

When to Seek Medical Advice

- Persistent serum folate > 20 ng/mL or red‑cell folate > 900 ng/mL.

- New neurological symptoms (numbness, tingling) while on high‑dose folate.

- Diagnosis of colorectal adenomas or a strong family history of colorectal cancer.

A clinician can evaluate the need for dose reduction, investigate underlying causes, and arrange appropriate follow‑up.

Summary

Folate is indispensable for DNA synthesis, methylation, and homocysteine regulation. While dietary intake from natural foods seldom leads to excess, high consumption of synthetic folic acid—through fortified foods and supplements—can push serum and red‑cell folate into potentially harmful ranges. The most serious risks involve masking vitamin B12 deficiency, possible promotion of existing neoplastic lesions, and complications in individuals with renal impairment or those on certain medications.

Maintaining folate within the recommended range requires balanced nutrition, judicious supplement use, and periodic laboratory monitoring, especially for populations at higher risk of overexposure. By following the evidence‑based strategies outlined above, individuals can reap folate’s health benefits while minimizing the dangers of excess.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of abnormal Folate (Vitamin B9) levels?

The most frequent cause of elevated folate is the use of high‑dose folic acid supplements or excessive intake of fortified foods that together exceed the tolerable upper intake level. Conversely, low folate levels are most often due to inadequate dietary intake, chronic alcoholism, malabsorption disorders (e.g., celiac disease), or certain medications that impair folate metabolism.

How often should I get my Folate (Vitamin B9) tested?

For individuals not taking supplements, testing is generally unnecessary unless there are clinical signs of deficiency or risk factors (e.g., pregnancy, malabsorption). For those on high‑dose supplementation, with a history of B12 deficiency, or having renal disease, it is prudent to check serum and red‑cell folate at baseline and then every 8–12 weeks after any dose change. Annual testing may be appropriate for older adults on multivitamins to ensure levels remain within the normal range.

Can lifestyle changes improve my Folate (Vitamin B9) levels?

Absolutely. Increasing consumption of fresh leafy greens, legumes, and citrus fruits boosts natural folate intake. Reducing alcohol intake, ensuring adequate vitamin B12 status, and staying well‑hydrated support optimal folate metabolism and renal clearance. For those with low levels, these dietary adjustments can often normalize folate without the need for high‑dose supplements. Conversely, individuals with high levels should moderate fortified food consumption and reassess supplement dosing as part of their lifestyle management.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Always consult a healthcare professional.