Vitamin B12 Normal Range: Blood Test Interpretation

Reference Ranges

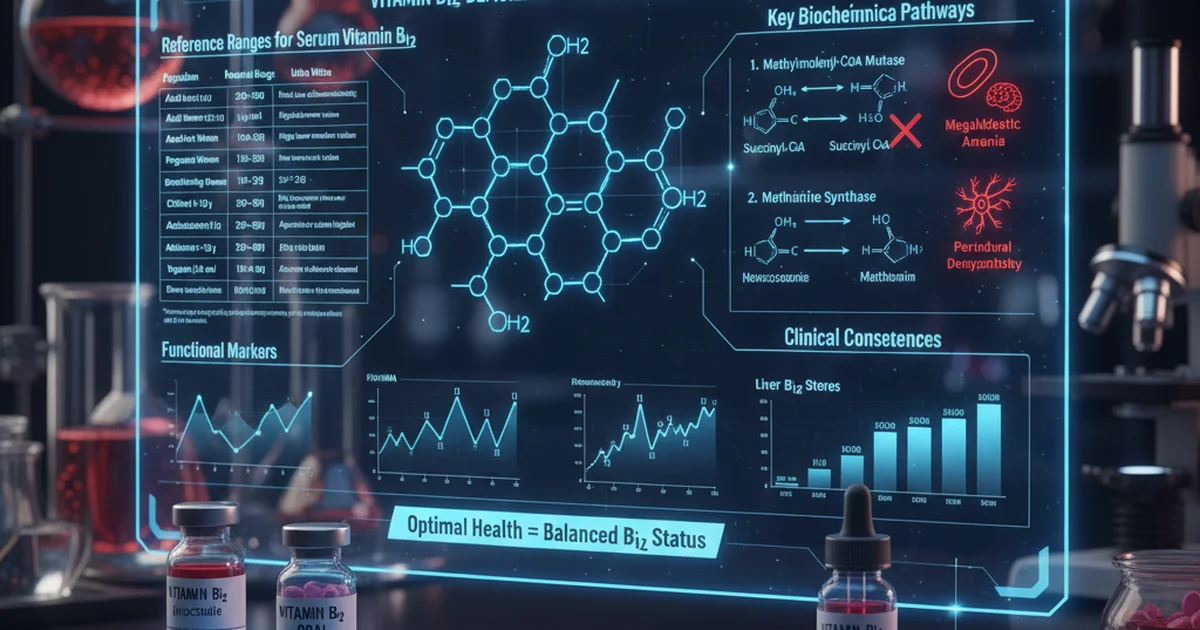

| Population | Normal Range | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Men (≥19 y) | 200‑900 | pg/mL | Most labs use chemiluminescence; 200 pg/mL is the lower limit for functional adequacy |

| Adult Women (≥19 y) | 180‑850 | pg/mL | Slightly lower median values reported in some female cohorts |

| Pregnant Women | 150‑650 | pg/mL | Physiologic dilution; deficiency risk higher in the 2nd‑3rd trimester |

| Breastfeeding Women | 170‑720 | pg/mL | Milk export of B12 may lower maternal serum levels |

| Children 1‑12 y | 200‑900 | pg/mL | Age‑related reference intervals are broad; infants often higher |

| Adolescents 13‑18 y | 210‑950 | pg/mL | Pubertal growth spurt can increase demand |

| Elderly ≥65 y | 200‑900 | pg/mL | Absorption declines; many labs add a “borderline” zone 200‑300 pg/mL |

| Vegans (≥6 mo) | 150‑550 | pg/mL | May be lower due to dietary exclusion; functional markers are useful |

Values are for serum/plasma total B12 measured by standard immunoassays. “Low” (<200 pg/mL) usually indicates deficiency, while “borderline” (200‑300 pg/mL) warrants functional testing (e.g., MMA, homocysteine).

Understanding Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) is a water‑soluble vitamin that serves as a cofactor for two essential enzymatic reactions:

- Methylmalonyl‑CoA mutase – converts methylmalonyl‑CoA to succinyl‑CoA, a step in odd‑chain fatty‑acid and amino‑acid metabolism.

- Methionine synthase – remethylates homocysteine to methionine, linking folate metabolism to DNA synthesis and myelin formation.

Deficiency disrupts these pathways, leading to megaloblastic anemia, neurologic dysfunction, and elevated methylmalonic acid (MMA) and homocysteine levels.

Dietary Sources and Bioavailability

Animal‑Based Sources (High Bioavailability)

| Food | Approx. B12 per 100 g | Bioavailability |

|---|---|---|

| Clams, oysters | 84 µg | >90 % |

| Liver (beef, lamb) | 70‑80 µg | 80‑90 % |

| Trout, salmon | 4‑5 µg | 70‑80 % |

| Beef, pork | 2‑3 µg | 60‑70 % |

| Dairy (milk, yogurt) | 0.4‑0.5 µg | 50‑60 % |

| Eggs (especially yolk) | 0.6 µg | 40‑50 % |

Animal proteins contain cobalamin bound to intrinsic factor‑compatible carriers, making absorption highly efficient.

Plant‑Based Sources (Low/Variable Bioavailability)

| Source | Approx. B12 per 100 g | Bioavailability |

|---|---|---|

| Nori (seaweed) | 0.5‑2 µg | 10‑30 % (depends on preparation) |

| Fortified breakfast cereals | 1‑6 µg | 20‑30 % (synthetic cyanocobalamin) |

| Nutritional yeast (fortified) | 2‑5 µg | 20‑30 % |

| Tempeh (fermented soy) | 0.1‑0.3 µg | Uncertain; often negligible |

Most plant foods contain B12 analogs (pseudovitamin B12) that are not biologically active. Regular consumption of fortified foods is the most reliable way for vegans and vegetarians to meet needs.

Factors Affecting Absorption

- Intrinsic factor (IF): Produced by gastric parietal cells; essential for ileal uptake.

- Gastric acidity: Low stomach acid (hypochlorhydria, common in the elderly or after PPIs) impairs release of B12 from food proteins.

- Ileal health: Crohn’s disease, surgical resection, or bacterial overgrowth can reduce IF‑mediated absorption.

- Medication interactions: Metformin, nitrous oxide, and certain anticonvulsants can interfere with intracellular B12 metabolism.

Key point: Even with adequate intake, absorption may be compromised; functional testing is valuable when risk factors exist.

Interpreting the Blood Test

Primary Test: Serum Total B12

- <200 pg/mL – Deficient; most clinicians initiate treatment and order MMA/homocysteine to confirm functional impact.

- 200‑300 pg/mL – Borderline/Indeterminate; interpretation depends on symptoms and secondary markers.

- >300 pg/mL – Generally considered adequate, though extremely high levels (>900 pg/mL) can indicate supplementation excess or assay interference.

Functional Markers

| Marker | Interpretation (if serum B12 borderline) |

|---|---|

| Methylmalonic Acid (MMA) | ↑ suggests true intracellular deficiency |

| Homocysteine | ↑ indicates impaired methionine synthase; less specific (folate, B6 also affect) |

| Holotranscobalamin (active B12) | Directly reflects IF‑bound B12; <35 pmol/L often signals deficiency |

Clinical tip: In asymptomatic patients with borderline serum B12, a raised MMA is the most reliable trigger for treatment.

Red Blood Cell (RBC) Folate vs. B12

Because B12 and folate share a metabolic pathway, simultaneous low folate can mask B12‑related anemia. Always assess both nutrients when macrocytosis is present.

Dietary Strategies to Optimize B12

- Prioritize high‑bioavailability foods

- Include at least two servings of animal protein (e.g., fish, meat, dairy) per day for omnivores.

- For vegetarians

- Use fortified plant milks, cereals, or nutritional yeast daily.

- Consider a B12 supplement (25‑100 µg cyanocobalamin or methylcobalamin) to cover the gap.

- For vegans

- Aim for 250 µg of fortified B12 per day, split into two doses to improve absorption.

- Periodically test serum B12 and MMA to verify adequacy.

- Elderly or patients on acid‑suppressing medication

- Choose sublingual or high‑dose oral supplements (≥500 µg) which can be absorbed via passive diffusion.

- Intramuscular (IM) injections (1000 µg) are reserved for severe malabsorption or neurologic symptoms.

Actionable advice: Keep a simple food log for a week, tally B12 intake, and compare to the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) – 2.4 µg for adults. Most people meet the RDA through diet, but bioavailability and absorption matter more than raw numbers.

Supplementation: Forms, Dosage, and Safety

| Form | Typical Dose (Adults) | Frequency | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyanocobalamin (tablet, sublingual) | 25‑1000 µg | Daily or weekly (high dose) | Most studied; converted to active forms in the body |

| Methylcobalamin (tablet, lozenge) | 25‑1000 µg | Daily | Directly active; may be preferred for neurologic symptoms |

| Hydroxocobalamin (IM injection) | 1000 µg | Every 1‑3 months | Longer half‑life; used for severe deficiency |

| Nasal spray (cobalamin) | 500‑1000 µg | Weekly | Useful for patients with GI malabsorption |

When to Use High‑Dose Oral Therapy

- Age > 65 y with mild‑to‑moderate deficiency

- Metformin users (≥2 g/day)

- PPI/H2‑blocker long‑term users

- Patients refusing IM injections

Evidence note: Studies show that 500‑1000 µg oral cyanocobalamin daily achieves comparable serum rises to monthly IM injections in most adults, thanks to passive diffusion accounting for ~1 % of the dose.

Safety Profile

- Vitamin B12 has no known toxicity at typical supplemental levels; excess is excreted in urine.

- Rare allergic reactions to the injectable form (hydroxocobalamin) may cause flushing or rash.

- Cyanocobalamin contains a cyanide moiety, but the amount released is negligible and safe for the general population.

Key recommendation: For most healthy adults, a daily 25‑100 µg oral supplement is sufficient to maintain serum >300 pg/mL, especially if dietary intake is marginal.

Managing Specific Clinical Situations

1. Pernicious Anemia

- Autoimmune destruction of parietal cells → absent intrinsic factor.

- Treatment: Lifelong IM hydroxocobalamin 1000 µg monthly, or high‑dose oral (≥1000 µg daily) if IM is not feasible.

- Monitor MMA and neurologic status every 3‑6 months initially.

2. Post‑Gastrectomy or Ileal Resection

- Reduced IF production or loss of absorption site.

- Therapy: IM injections or high‑dose oral supplementation (≥2000 µg daily).

3. Pregnancy

- Increased fetal demand; deficiency linked to neural tube defects.

- Supplementation: 6‑10 µg daily (prenatal vitamin) is adequate for most; higher doses (25‑100 µg) if borderline serum B12.

4. Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

- Elevated serum B12 may reflect reduced clearance, not true sufficiency.

- Rely on functional markers (MMA) to guide therapy.

Practical Steps for Patients and Clinicians

- Screen at-risk populations (elderly, vegans, bariatric surgery patients, chronic medication users) every 1‑2 years.

- Order a panel: serum B12, MMA, homocysteine, complete blood count, and folate when anemia or neurologic signs are present.

- Interpretation workflow

- Serum <200 pg/mL → Diagnose deficiency → initiate treatment.

- 200‑300 pg/mL → Check MMA/homocysteine → treat if elevated.

- >300 pg/mL and symptomatic → Evaluate for functional B12 or other causes (e.g., folate deficiency).

- Educate patients on food sources, the importance of regular intake, and the limitations of “high‑dose” over‑supplementation.

- Re‑check serum B12 and MMA 8‑12 weeks after initiating therapy to confirm biochemical response.

Actionable tip: Set a reminder in the EMR to revisit B12 status after therapy changes; this improves adherence and prevents relapses.

Lifestyle Factors that Influence B12 Status

- Alcohol: Heavy intake impairs absorption and liver storage.

- Smoking: May lower serum B12 through oxidative mechanisms.

- Physical activity: Regular exercise supports gut motility, indirectly aiding nutrient absorption.

- Stress: Chronic stress can affect gastric acid secretion, potentially reducing B12 release from food.

Recommendation: Encourage a balanced lifestyle—moderate alcohol, smoking cessation, regular exercise, and stress‑management techniques—to support optimal B12 metabolism.

Summary

Vitamin B12 is indispensable for DNA synthesis, red‑cell formation, and neurologic health. Understanding the normal serum range (≈200‑900 pg/mL) and the clinical meaning of borderline values empowers clinicians to diagnose deficiency early. Dietary intake from animal sources provides the most bioavailable form, but fortified foods and supplements bridge the gap for vegetarians, vegans, and individuals with malabsorption. High‑dose oral cobalamin is an effective, safe alternative to injections for most cases, while lifelong parenteral therapy remains the gold standard for pernicious anemia and severe malabsorption. Regular screening of at‑risk groups, combined with functional markers like MMA, ensures accurate interpretation and timely intervention.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of abnormal Vitamin B12 levels?

The leading cause of low B12 is impaired absorption, most often due to intrinsic factor deficiency (pernicious anemia) or age‑related decline in stomach acid. In dietary terms, strict vegan diets without fortified foods are a frequent source of deficiency. Elevated B12 is less common and usually reflects excess supplementation, liver disease, or myeloproliferative disorders that release stored B12 into the bloodstream.

How often should I get my Vitamin B12 tested?

- General adult population: Every 2–3 years, or sooner if symptoms appear.

- At‑risk groups (elderly ≥ 65 y, vegans, bariatric surgery patients, chronic PPI/metformin users): Annually or after any change in diet/medication.

- During pregnancy: At the first prenatal visit and again in the second trimester if intake is borderline.

Can lifestyle changes improve my Vitamin B12 levels?

Yes. Optimizing gastric acid by reducing excessive antacid use, limiting alcohol, quitting smoking, and maintaining a balanced diet rich in animal products or fortified foods can enhance absorption. Regular physical activity supports gut health, and managing stress helps preserve normal gastric secretions. When lifestyle modifications are insufficient, targeted supplementation remains the most reliable method to correct deficiency.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Always consult a healthcare professional.