Vitamin D Normal Range: Deficient vs. Optimal Levels

Vitamin D (specifically 25‑hydroxyvitamin D, or 25(OH)D) is the principal circulating form used to assess the body’s vitamin D status. It reflects intake from food, supplements, and skin synthesis after ultraviolet‑B (UV‑B) exposure. Determining whether a level is deficient, sufficient, or optimal guides clinical decisions, dietary planning, and supplementation strategies. This article provides an evidence‑based overview of the normal range, the health implications of low versus optimal levels, dietary sources, bioavailability, and practical supplementation advice.

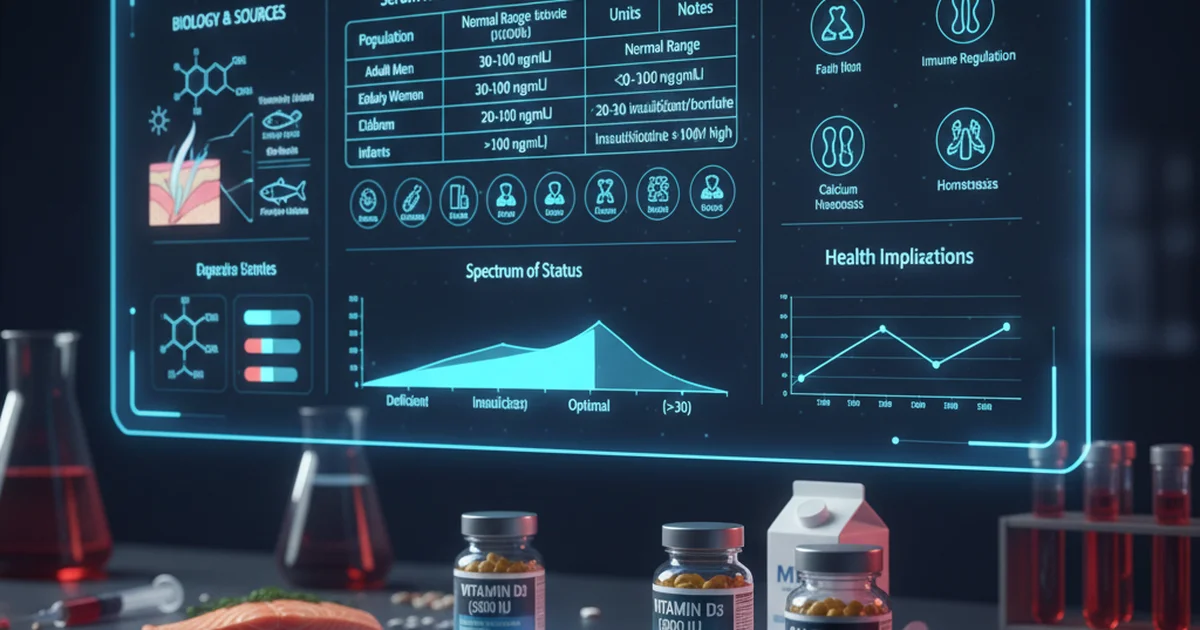

Reference Ranges for 25‑Hydroxyvitamin D

| Population | Normal Range | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Men (≥19 y) | 30–100 | ng/mL | Most labs consider ≥30 ng/mL sufficient; >50 ng/mL may be optimal for bone health |

| Adult Women (≥19 y) | 30–100 | ng/mL | Same thresholds as men; pregnant women often aim for ≥40 ng/mL |

| Children (1‑17 y) | 30–100 | ng/mL | Levels <20 ng/mL are considered deficient; >30 ng/mL supports growth |

| Older Adults (≥65 y) | 30–100 | ng/mL | Higher end may reduce fall risk and fractures |

| Athletes / High‑Performance | 40–120 | ng/mL | Some sports medicine groups target >40 ng/mL for muscle function |

| Patients with Malabsorption or Chronic Kidney Disease | 30–100* | ng/mL | *Target may be individualized; avoid >150 ng/mL due to toxicity risk |

| General Population (screening) | 20–80 | ng/mL | Broad range used by public‑health labs; clinicians interpret based on risk factors |

*“Normal” ranges can vary by assay methodology and geographic location. The values above reflect the most widely accepted clinical cut‑offs:

- Deficient: <20 ng/mL

- Insufficient: 20–29 ng/mL

- Sufficient: 30–49 ng/mL

- Optimal/Target: 50–80 ng/mL (many experts advocate 60–80 ng/mL for extra‑skeletal benefits)

Why the Distinction Matters

Bone Health

- Deficiency impairs calcium absorption, leading to osteomalacia in adults and rickets in children.

- Optimal levels improve bone mineral density (BMD) and reduce fracture risk, especially in post‑menopausal women and older men.

Immune Modulation

- Vitamin D receptors are present on immune cells. Adequate 25(OH)D supports innate immunity and may lower the severity of respiratory infections.

Metabolic and Cardiovascular Effects

- Observational data link optimal levels (≥50 ng/mL) with improved insulin sensitivity, lower blood pressure, and reduced inflammation markers.

Musculoskeletal Performance

- Athletes with 25(OH)D > 40 ng/mL often show better muscle strength, faster recovery, and fewer stress fractures.

Dietary Sources of Vitamin D

| Food | Approx. Vitamin D Content (IU per serving) | Bioavailability Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fatty fish (salmon, mackerel, sardines) | 400–600 | Highly bioavailable; omega‑3 fats aid absorption |

| Cod liver oil (1 tsp) | 450 | Concentrated source; also provides vitamin A |

| Egg yolk (large) | 40 | Vitamin D is bound to phospholipids, enhancing absorption |

| Fortified dairy (milk, yogurt) | 100–130 | Calcium and protein co‑present improve utilization |

| Fortified plant milks (soy, almond) | 100–120 | Similar to dairy; check for vitamin D2 vs D3 |

| Beef liver (3 oz) | 50 | Small amount; also provides iron |

| UV‑treated mushrooms (portobello) | 200–400 (as D2) | D2 is less potent than D3 but still contributes |

| Cheese (hard varieties) | 6–12 | Minor source; contributes cumulatively |

Key Points

- Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol), found in animal foods and synthesized by skin, is more potent and has a longer half‑life than vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol) from plant sources.

- Fat content enhances absorption; consuming vitamin D with a modest amount of dietary fat (≈5 g) maximizes bioavailability.

- Fortified foods are essential for those with limited sun exposure, especially in higher latitudes or during winter months.

Bioavailability: From Food to Serum

Digestion and Micelle Formation

- Vitamin D is fat‑soluble; it incorporates into micelles with the aid of bile salts.

- Adequate bile flow and pancreatic lipase activity are crucial. Individuals with cholestasis or pancreatic insufficiency often exhibit poor absorption.

Enterocyte Uptake

- Once inside the intestinal cell, vitamin D binds to intracellular binding proteins and is incorporated into chylomicrons.

Lymphatic Transport

- Chylomicrons enter the lymphatic system, bypassing the portal vein, and eventually reach the bloodstream.

Hepatic 25‑Hydroxylation

- In the liver, vitamin D is converted to 25(OH)D by the enzyme CYP2R1. This step determines the circulating level measured in labs.

Renal Activation (Optional)

- The kidney converts 25(OH)D to the active hormone 1,25‑dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol) when calcium or phosphate demand rises.

Factors Reducing Bioavailability

- Low dietary fat → impairs micelle formation.

- Malabsorption syndromes (celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, celiac sprue).

- Bile acid sequestrants (e.g., cholestyramine) bind vitamin D and reduce uptake.

- Obesity → vitamin D is sequestered in adipose tissue, lowering serum levels despite adequate intake.

Supplementation: When Food Isn’t Enough

Who Should Consider Supplements?

- Individuals with limited sun exposure (e.g., indoor workers, high‑latitude residents).

- Older adults whose skin synthesizes less vitamin D.

- People with darker skin tones, as melanin reduces UV‑B penetration.

- Patients with malabsorption, bariatric surgery, or chronic kidney disease.

- Pregnant and lactating women, especially if dietary intake is low.

Choosing the Right Form

| Form | Vitamin D Type | Typical Dose Range | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral tablets/capsules | D3 (cholecalciferol) | 400–5,000 IU/day (maintenance) | Most potent, long half‑life |

| Liquid drops | D3 | 400–2,000 IU/day | Easy for children or those with swallowing difficulties |

| Softgels with oil | D3 in olive or MCT oil | 1,000–4,000 IU/day | Enhanced absorption due to oil base |

| Prescription high‑dose (e.g., 50,000 IU weekly) | D2 or D3 | 50,000 IU weekly for 8 weeks (repletion) | Rapid correction of severe deficiency |

| Combined calcium‑vitamin D tablets | D3 + calcium carbonate | 600–1,200 IU D3 + 500–1,200 mg Ca | Convenient for bone health |

Clinical Tip: For most adults, 1,000–2,000 IU/day of vitamin D3 safely raises serum 25(OH)D by ~10 ng/mL over 8–12 weeks. Adjust based on baseline level, body weight, and target range.

Loading (Repletion) vs. Maintenance

- Loading Phase: 50,000 IU vitamin D3 once weekly for 6–8 weeks (or 6,000 IU daily) is commonly used to correct levels <20 ng/mL.

- Maintenance Phase: After repletion, a daily dose of 1,000–2,000 IU maintains levels within the optimal window.

Monitoring and Safety

- Serum 25(OH)D testing should be repeated 8–12 weeks after initiating or changing dose.

- Toxicity is rare but can occur with chronic intake >10,000 IU/day, leading to hypercalcemia, nephrolithiasis, and vascular calcification.

- Hypercalcemia symptoms: nausea, vomiting, polyuria, weakness, and cardiac arrhythmias.

Practical Strategies to Optimize Vitamin D Status

Assess Sun Exposure

- Aim for 10–30 minutes of midday sun on face, arms, and legs 2–3 times per week, depending on skin type and season.

- Use sunscreen after the initial exposure window to protect against UV damage.

Incorporate Vitamin D‑Rich Foods Daily

- Example menu: fortified oatmeal with almond milk (100 IU), scrambled eggs (40 IU), and a salmon lunch (500 IU).

Pair Vitamin D with Healthy Fats

- Add avocado, nuts, or a drizzle of olive oil to meals containing vitamin D sources.

Choose the Right Supplement

- For individuals with malabsorption, select oil‑based softgels or liquid drops for better uptake.

- Verify that the supplement provides vitamin D3, unless dietary restrictions necessitate D2.

Tailor Dose to Body Weight

- Rough rule: add ~1,000 IU for each 20 lb (≈9 kg) above 150 lb (≈68 kg) to achieve optimal serum levels.

Monitor Periodically

- Test at baseline, after loading, and then annually if you remain in the maintenance phase.

Address Co‑Factors

- Magnesium is required for the enzymatic conversion of vitamin D to its active forms; ensure intake of 300–400 mg/day from foods like nuts, seeds, and leafy greens.

- Vitamin K2 works synergistically to direct calcium to bone rather than soft tissues; consider fermented foods (e.g., natto) or a K2 supplement if bone health is a priority.

Vitamin D Deficiency vs. Optimal Levels: Clinical Implications

| Parameter | Deficient (<20 ng/mL) | Insufficient (20‑29 ng/mL) | Sufficient (30‑49 ng/mL) | Optimal (≥50 ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium absorption | ↓ 10–15 % | Slightly reduced | Near normal | Maximal efficiency |

| PTH (parathyroid hormone) | Elevated (secondary hyperparathyroidism) | Mildly elevated | Normal | Suppressed to optimal range |

| Bone turnover markers | ↑ (bone loss) | ↑ (moderate) | Balanced | Balanced, may favor formation |

| Muscle strength | ↓ (frailty) | Slightly reduced | Normal | Improved power, reduced falls |

| Immune response | ↑ infection risk | Moderate risk | Adequate | Potentially enhanced antiviral defenses |

| Cardiovascular risk | ↑ hypertension, endothelial dysfunction | Slightly ↑ | Baseline | May be lowered (observational) |

| Mood & cognition | ↑ depressive symptoms | Moderate | Normal | Possible neuroprotective effect |

Take‑away: While “sufficient” levels prevent overt bone disease, optimal levels (≥50 ng/mL) appear to confer additional musculoskeletal, metabolic, and immunologic benefits. Individual goals should be personalized based on age, comorbidities, and lifestyle.

Action Plan for Healthcare Professionals

- Screen High‑Risk Populations – Include 25(OH)D testing in annual labs for older adults, patients with osteoporosis, chronic kidney disease, malabsorption, and those on glucocorticoids.

- Interpret Results in Context – Consider season, latitude, BMI, and concurrent medications when evaluating a serum value.

- Prescribe Targeted Doses – Use loading regimens for documented deficiency, then transition to a maintenance dose that aims for a serum target of 50–80 ng/mL.

- Educate Patients – Emphasize the synergy of sunlight, diet, and supplementation; provide simple meal plans and safe sun‑exposure guidelines.

- Re‑evaluate Annually – Adjust dosing based on follow‑up labs, changes in weight, or new medical conditions.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of abnormal Vitamin D (25-Hydroxy) levels?

The leading cause of low 25(OH)D is insufficient UV‑B exposure, which may result from living at high latitudes, spending most time indoors, using extensive sunscreen, or having dark skin that reduces synthesis. Dietary insufficiency and malabsorption syndromes also contribute, but inadequate sun exposure accounts for the majority of cases in the general population.

How often should I get my Vitamin D (25-Hydroxy) tested?

For individuals without risk factors, testing every 2–3 years is reasonable. Those undergoing supplementation, with osteoporosis, chronic kidney disease, obesity, or malabsorption should have serum 25(OH)D checked 8–12 weeks after initiating or adjusting a dose, then annually to ensure levels remain within the target range.

Can lifestyle changes improve my Vitamin D (25-Hydroxy) levels?

Absolutely. Regular, safe sun exposure (10–30 minutes of midday UV‑B a few times per week) can raise serum levels by 5–15 ng/mL. Adding vitamin D‑rich foods (fatty fish, fortified dairy/plant milks, eggs) and consuming them with healthy fats enhances absorption. Weight loss in obese individuals also releases sequestered vitamin D, modestly increasing circulating concentrations. When lifestyle measures are insufficient, low‑dose supplementation can safely bridge the gap to optimal levels.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Always consult a healthcare professional.