Ferritin Blood Test: Procedure and Results Explained

Introduction

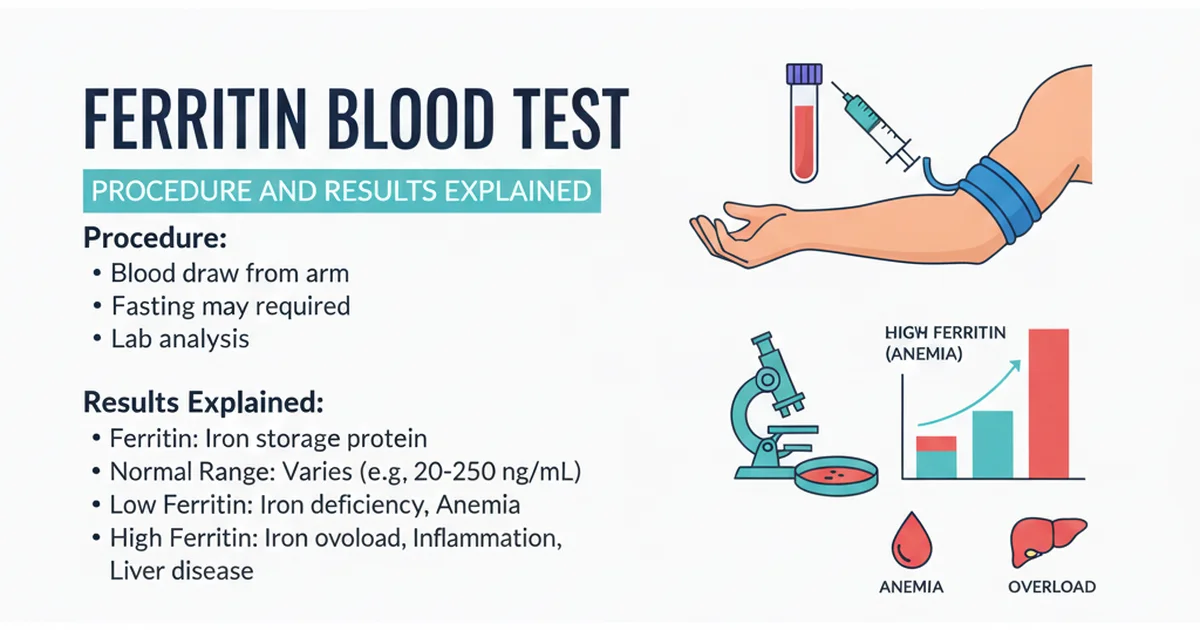

Ferritin is the primary intracellular protein that stores iron and releases it in a controlled fashion. Because the amount of ferritin in the bloodstream reflects the total body iron reserve, the Ferritin Blood Test is the most widely used laboratory tool for assessing iron status. Understanding how the test is performed, what the numbers mean, and how diet, bioavailability, and supplementation influence ferritin levels is essential for anyone dealing with anemia, iron overload, or general health optimization.

How the Ferritin Test Is Performed

Blood Sample Collection

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Preparation | The patient is asked to fast for 8–12 hours only if the clinician orders additional iron studies that require fasting. No special preparation is needed solely for ferritin. |

| Venipuncture | A standard 5‑ml blood draw is taken from a peripheral vein (usually the median cubital vein). The tube contains clot activator for serum or lithium heparin for plasma, depending on the lab’s protocol. |

| Processing | The sample is allowed to clot (serum) or is centrifuged (plasma) within 30 minutes. Ferritin is stable at room temperature for up to 24 hours; most labs store it at 2–8 °C until analysis. |

| Analysis | Automated immunoassays (e.g., chemiluminescent immunoassay) quantify ferritin concentration. Results are reported in nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL) or micrograms per liter (µg/L) (equivalent units). |

When to Order the Test

- Unexplained fatigue, weakness, or shortness of breath

- Suspected iron‑deficiency anemia (especially in women of child‑bearing age)

- Monitoring response to iron therapy

- Evaluation of iron overload disorders (hemochromatosis, thalassemia)

- Chronic inflammatory conditions where ferritin may be elevated as an acute‑phase reactant

Interpreting Ferritin Results

Ferritin levels must be interpreted in the context of age, sex, physiological status, and concurrent disease. Below is a comprehensive reference‑range table that reflects typical laboratory cut‑offs.

| Population | Normal Range | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Men (≥ 19 y) | 30 – 400 | ng/mL | Slightly higher in smokers |

| Adult Women (≥ 19 y) | 15 – 150 | ng/mL | Lower in pre‑menopausal women |

| Pregnant Women (1st trimester) | 12 – 140 | ng/mL | Declines as pregnancy progresses |

| Post‑menopausal Women | 20 – 200 | ng/mL | Gradual rise after menopause |

| Children (1‑12 y) | 7 – 140 | ng/mL | Age‑dependent; higher in toddlers |

| Adolescents (13‑18 y) | 12 – 300 | ng/mL | Rapid increase during growth spurts |

| Elderly (≥ 65 y) | 20 – 300 | ng/mL | May be elevated by inflammation |

Key interpretation points

- Low ferritin (< 15 ng/mL for women, < 30 ng/mL for men) strongly suggests iron deficiency, even before anemia develops.

- Borderline ferritin (15‑30 ng/mL for women, 30‑70 ng/mL for men) may indicate early depletion; interpretation should be paired with transferrin saturation and serum iron.

- High ferritin (> 400 ng/mL for men, > 150 ng/mL for women) can reflect iron overload or an acute‑phase response. Additional tests (e.g., transferrin saturation, C‑reactive protein) help differentiate.

Causes of Abnormal Ferritin Levels

Low Ferritin

- Dietary iron deficiency (inadequate intake of heme or non‑heme iron)

- Chronic blood loss (menstruation, gastrointestinal bleeding, parasitic infections)

- Increased physiological demand (pregnancy, growth, endurance training)

- Malabsorption (celiac disease, bariatric surgery, inflammatory bowel disease)

- Hookworm infection or other parasitic infestations

High Ferritin

- Hereditary hemochromatosis (HFE gene mutations)

- Secondary iron overload (multiple blood transfusions, chronic liver disease)

- Chronic inflammatory states (rheumatoid arthritis, infections, malignancy) – ferritin acts as an acute‑phase reactant

- Alcoholic liver disease and non‑alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

- Metabolic syndrome and obesity (low‑grade inflammation)

Dietary Sources of Iron and Their Impact on Ferritin

Iron exists in two dietary forms:

| Form | Source | Typical Absorption Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Heme iron | Red meat, poultry, fish, organ meats | 15 % – 35 % |

| Non‑heme iron | Legumes, fortified cereals, spinach, nuts, seeds | 2 % – 20 % (highly variable) |

High‑Ferritin‑Supporting Foods

- Lean red meat (beef, lamb) – richest natural heme iron source, also supplies vitamin B12 and zinc.

- Chicken liver – exceptionally high in heme iron and vitamin A, useful for rapid repletion.

- Shellfish (clams, oysters, mussels) – excellent heme iron and high zinc content.

- Fortified breakfast cereals – often contain 18 mg of elemental iron per serving; absorption boosted when eaten with vitamin C‑rich foods.

Plant‑Based Iron Sources

- Legumes (lentils, chickpeas, beans) – provide 3‑5 mg iron per cup; combine with vitamin C (e.g., bell peppers) to enhance uptake.

- Dark leafy greens (spinach, kale, Swiss chard) – contain iron bound to oxalates, which inhibit absorption; cooking reduces oxalate content.

- Nuts and seeds (pumpkin seeds, cashews, almonds) – modest iron; useful as snacks or salad toppings.

Enhancers of Non‑Heme Iron Absorption

- Vitamin C – reduces ferric (Fe³⁺) to ferrous (Fe²⁺) form, markedly improving absorption (up to 3‑fold). Citrus fruits, strawberries, tomatoes, and bell peppers are excellent sources.

- Meat, fish, poultry (the “meat factor”) – even a small amount of animal protein can increase non‑heme iron uptake.

Inhibitors of Iron Absorption

- Phytates (found in whole grains, legumes, nuts) – bind iron; soaking, sprouting, or fermenting foods reduces phytate levels.

- Polyphenols (tea, coffee, red wine) – form insoluble complexes; avoid consuming these beverages with iron‑rich meals.

- Calcium (dairy products, supplements) – competes for absorption; separate calcium intake from iron‑rich meals by at least two hours.

Bioavailability: From Diet to Ferritin

- Ingestion – Iron is released from food in the stomach; heme iron remains in a protein-bound state, while non‑heme iron is released as ferric iron (Fe³⁺).

- Reduction – Duodenal enterocytes reduce Fe³⁺ to Fe²⁺ via duodenal cytochrome b (Dcytb). Vitamin C and the acidic gastric environment facilitate this step.

- Transport into Enterocytes – Divalent metal transporter‑1 (DMT1) shuttles Fe²⁺ across the apical membrane.

- Storage or Export – Inside the cell, iron may be stored as ferritin or exported via ferroportin. Hepcidin, a liver‑derived hormone, regulates ferroportin; high hepcidin (as seen in inflammation) blocks iron release, lowering serum ferritin despite adequate stores.

- Systemic Distribution – Exported iron binds transferrin in the plasma and is delivered to the bone marrow, spleen, and other tissues. Ferritin released into circulation reflects the intracellular storage pool.

Practical implication: Even with adequate dietary iron, high hepcidin levels (e.g., from chronic infection) can prevent ferritin rise. Conversely, low hepcidin (as in hereditary hemochromatosis) leads to excessive iron absorption and high ferritin.

Supplementation Strategies

When Supplementation Is Indicated

- Confirmed iron‑deficiency ferritin (< 15 ng/mL for women, < 30 ng/mL for men)

- Symptomatic individuals with borderline ferritin and high functional demand (athletes, pregnant women)

- Chronic blood loss where dietary changes alone are insufficient

Choosing the Right Form

| Form | Elemental Iron Content (≈) | Advantages | Common Side‑Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ferrous sulfate | 20 % | Inexpensive, well studied | GI upset, constipation |

| Ferrous gluconate | 12 % | Lower GI irritation | Similar but milder |

| Ferrous fumarate | 33 % | Higher elemental iron, good absorption | GI discomfort |

| Iron polysaccharide complex | 20‑25 % | Controlled release, fewer GI symptoms | Costlier |

| Heme iron polypeptide | 20‑25 % | Bypasses hepcidin regulation, high bioavailability | Limited availability |

| Liquid iron (e.g., ferrous bisglycinate) | 20 % | Useful for children or those with dysphagia | Taste issues |

Dosing Guidelines

- Adults: 100‑200 mg elemental iron per day for 3‑6 months is typical for repletion.

- Pregnant women: 27 mg elemental iron daily (often via prenatal vitamin) is recommended; higher therapeutic doses may be needed under medical supervision.

- Children: 3‑6 mg/kg elemental iron per day, divided into 2‑3 doses, depending on age and severity.

Important tip: Take iron on an empty stomach (30 minutes before meals) to maximize absorption, unless GI upset occurs; then take with a small amount of food and avoid calcium‑rich meals.

Monitoring and Safety

- Re‑check ferritin after 4‑6 weeks of therapy; a rise of 50‑100 ng/mL indicates effective absorption.

- Watch for iron overload: In patients with hereditary hemochromatosis or chronic liver disease, avoid supplementation unless ferritin is clearly low and hepcidin is suppressed.

- Adverse reactions – constipation, nausea, dark stools (harmless), or, rarely, iron‑induced oxidative injury. Use stool softeners or switch to a gentler formulation if needed.

Lifestyle Measures to Optimize Ferritin

- Meal timing – Pair iron‑rich meals with vitamin C sources; avoid tea/coffee within 1 hour of the meal.

- Cooking methods – Use cast‑iron cookware; up to 5 mg of iron can leach into acidic foods (tomato sauce, chili).

- Gut health – Maintain a balanced microbiome; chronic dysbiosis can impair iron absorption. Probiotic‑rich foods (yogurt, kefir) may support intestinal integrity.

- Exercise – Moderate endurance training can increase iron loss through sweat and hemolysis; athletes should monitor ferritin quarterly.

- Avoid excessive calcium – Space calcium supplements or dairy intake away from iron‑rich meals.

Ferritin in Special Populations

Pregnancy

- Ferritin naturally declines as plasma volume expands.

- Target range: 12‑140 ng/mL (first trimester), dropping to 8‑120 ng/mL later.

- Management: Prenatal vitamins with 27 mg elemental iron; if ferritin falls < 30 ng/mL, add therapeutic iron (100‑150 mg elemental) under obstetric guidance.

Athletes

- Intense training can cause “sports anemia” – functional iron deficiency with normal serum iron but low ferritin (< 30 ng/mL).

- Strategy: Iron‑rich diet, vitamin C timing, and periodic ferritin testing every 3 months during high‑intensity seasons.

Elderly

- Inflammation‑driven high ferritin is common; differentiate from true overload using transferrin saturation and inflammatory markers.

- Nutritional focus: Small, frequent iron‑rich meals with vitamin C to counteract reduced gastric acidity.

Actionable Take‑Home Checklist

If you suspect iron deficiency:

- Schedule a ferritin test (fasting not required).

- Review diet for heme and non‑heme sources; add vitamin C‑rich foods.

- Avoid tea/coffee and calcium with iron‑rich meals.

If ferritin is low:

- Discuss oral iron supplementation (type and dose) with your clinician.

- Re‑check ferritin in 4‑6 weeks; adjust dose based on response.

If ferritin is high:

- Evaluate for inflammation (CRP) or liver disease.

- Consider genetic testing for hemochromatosis if iron overload is suspected.

- Avoid unnecessary iron supplements; focus on managing underlying condition.

General maintenance:

- Eat a balanced diet containing at least 2‑3 servings of heme iron per week.

- Include a vitamin C source with each iron‑containing meal.

- Use cast‑iron cookware for acidic dishes.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of abnormal Ferritin levels?

The most frequent cause of low ferritin is dietary iron deficiency combined with chronic blood loss, especially in pre‑menopausal women due to menstruation. For high ferritin, chronic inflammation is the leading factor; ferritin acts as an acute‑phase reactant, rising in conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, infection, or liver disease. Distinguishing true iron overload from inflammation requires additional tests like transferrin saturation and inflammatory markers.

How often should I get my Ferritin tested?

- Baseline testing is recommended if you have symptoms of anemia, are pregnant, or have a condition affecting iron metabolism.

- During iron therapy, repeat the test after 4‑6 weeks to assess response.

- For chronic conditions (e.g., inflammatory disease, hemochromatosis), monitoring every 6‑12 months is reasonable.

- Athletes or individuals with high physiological demand may benefit from quarterly checks during intense training periods.

Can lifestyle changes improve my Ferritin levels?

Absolutely. Optimizing dietary iron intake, pairing iron‑rich foods with vitamin C, and avoiding absorption inhibitors (tea, coffee, calcium) can raise ferritin naturally. Cooking with cast‑iron cookware adds extra iron to meals. Maintaining gut health, managing chronic inflammation, and moderating alcohol intake also support appropriate ferritin levels. In many cases, these adjustments complement or even replace the need for supplemental iron, especially when ferritin is only mildly low.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Always consult a healthcare professional.