Ferritin Normal Range by Age and Gender

Ferritin is the primary intracellular protein that stores iron and releases it in a controlled fashion. Because ferritin circulates in the blood in proportion to total body iron stores, serum ferritin is the most widely used laboratory marker for assessing iron status. Understanding the normal range of ferritin across the lifespan and between sexes is essential for diagnosing iron deficiency, iron overload, and related health concerns. This article provides an evidence‑based overview of ferritin reference ranges, dietary sources of iron that influence ferritin, factors that affect iron bioavailability, and practical guidance on supplementation.

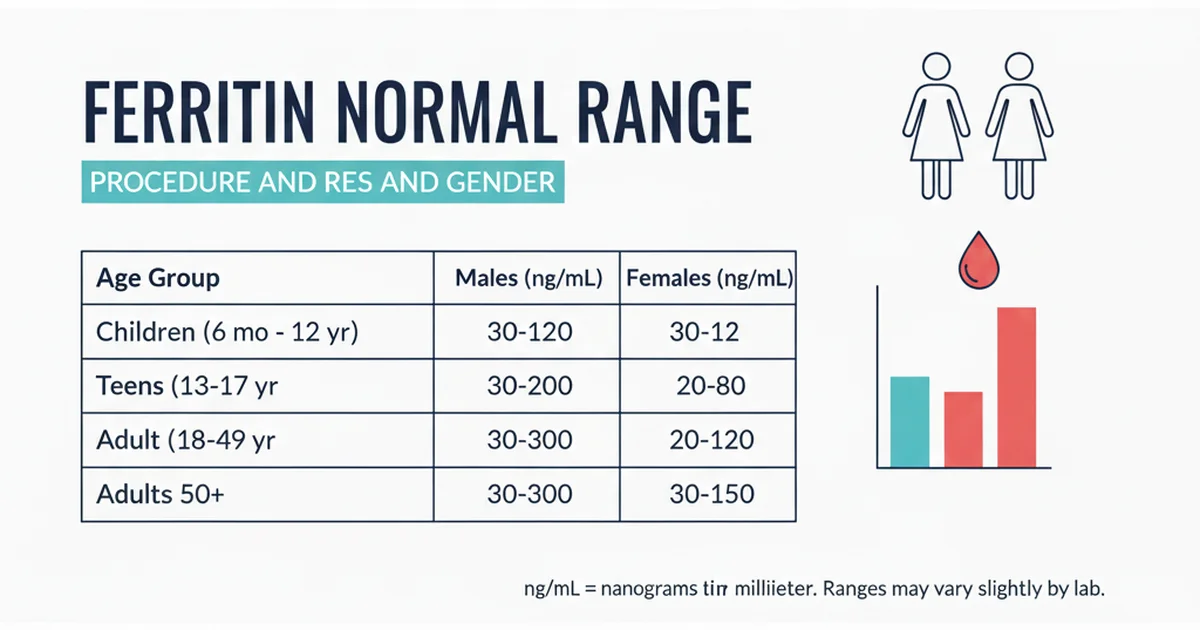

Reference Ranges Table

| Population | Normal Range | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Men (19‑64 yr) | 30‑400 | ng/mL | Upper limit may be lower in labs that use high‑sensitivity assays |

| Adult Women (19‑49 yr, premenopausal) | 15‑150 | ng/mL | Menstrual blood loss reduces average levels |

| Adult Women (≥50 yr, postmenopausal) | 30‑300 | ng/mL | Levels rise after menopause due to loss of menstrual loss |

| Adolescents (12‑18 yr, boys) | 20‑300 | ng/mL | Pubertal growth spurt increases iron demand |

| Adolescents (12‑18 yr, girls) | 10‑150 | ng/mL | Menarche adds a regular iron loss |

| Children (1‑11 yr) | 7‑140 | ng/mL | Wide range reflects rapid growth and variable diet |

| Infants (0‑12 mo) | 20‑200 | ng/mL | Cord blood ferritin is high; declines as infant stores are used |

| Pregnant Women (first trimester) | 12‑150 | ng/mL | Recommended to maintain >30 ng/mL to support fetal development |

| Pregnant Women (second/third trimester) | 12‑150 | ng/mL | Iron demand spikes; supplementation often required |

| Elderly (≥65 yr, both sexes) | 30‑300 | ng/mL | Chronic disease can elevate ferritin independent of iron stores |

Normal ranges are expressed in nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL). Individual laboratories may report slightly different cut‑offs based on assay methodology and population data.

Why Ferritin Matters

- Indicator of Iron Stores: Ferritin reflects the amount of iron stored in the liver, spleen, and bone marrow. Low ferritin is the earliest biochemical sign of iron deficiency, often preceding anemia.

- Acute‑Phase Reactant: Ferritin rises during inflammation, infection, or liver disease, potentially masking true iron deficiency.

- Risk Stratifier: Elevated ferritin (>400 ng/mL in men, >300 ng/mL in women) can signal iron overload disorders such as hereditary hemochromatosis or metabolic syndrome‑related hyperferritinemia.

Because ferritin is influenced by both iron status and inflammation, interpretation should always consider clinical context, complete blood count (CBC) results, and inflammatory markers (e.g., C‑reactive protein) when available.

Dietary Iron Sources and Their Influence on Ferritin

Iron exists in two dietary forms:

| Form | Typical Sources | Absorption Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Heme Iron | Red meat, poultry, fish, organ meats | 15‑35 % (least affected by dietary inhibitors) |

| Non‑Heme Iron | Legumes, nuts, seeds, whole grains, fortified cereals, leafy greens | 2‑20 % (strongly modulated by enhancers/inhibitors) |

Key Food Groups

- Red Meat & Poultry – Beef, lamb, chicken liver, and turkey provide dense heme iron (≈2.5 mg per 3 oz). Regular consumption is the most reliable way to raise ferritin, especially for individuals with high iron demands (adolescents, pregnant women).

- Seafood – Oysters, clams, mussels, and sardines are excellent heme sources; a 3‑oz serving of clams supplies ~23 mg of iron.

- Legumes & Pulses – Lentils, chickpeas, black beans, and soy products deliver 2‑4 mg of non‑heme iron per half‑cup cooked. Soaking, sprouting, and fermenting improve bioavailability.

- Dark‑Leafy Greens – Spinach, Swiss chard, and kale contain 1‑2 mg of non‑heme iron per cup raw; however, oxalates can inhibit absorption.

- Fortified Grains & Cereals – Many breakfast cereals are fortified with up to 18 mg of iron per serving; these are especially valuable for children and women of reproductive age.

- Nuts & Seeds – Pumpkin seeds, sesame seeds, and cashews provide modest iron (≈1 mg per ounce) and also contain vitamin E and healthy fats.

Enhancers of Iron Absorption

- Vitamin C (Ascorbic Acid) – Consuming 50‑100 mg of vitamin C with a non‑heme iron source can double absorption. Citrus fruits, strawberries, bell peppers, and broccoli are convenient pairings.

- Meat, Fish, Poultry (MFP) Factor – Even a small amount of heme protein (≈10 g) added to a plant‑based meal can increase non‑heme iron uptake by 30‑40 %.

- Organic Acids – Citric, malic, and lactic acids (found in fermented foods) chelate iron and improve solubility.

Inhibitors of Iron Absorption

- Phytates – Present in whole grains, legumes, and nuts; can bind iron and reduce absorption by up to 50 %. Soaking, sprouting, and fermenting diminish phytate levels.

- Polyphenols – Tea, coffee, and some herbs contain tannins that strongly inhibit iron uptake. Avoid drinking these beverages with iron‑rich meals.

- Calcium – High calcium intake (≥300 mg) at the same time as iron can modestly impede absorption; spacing dairy or calcium supplements 2 hours apart from iron‑rich meals helps.

- Soy Isoflavones – In large amounts, soy protein can interfere with iron absorption; moderate consumption is usually fine.

From Diet to Ferritin: The Physiological Pathway

- Ingestion – Iron is consumed as heme (from animal tissue) or non‑heme (from plant foods).

- Gastric Release – Stomach acid (hydrochloric acid) reduces ferric iron (Fe³⁺) to ferrous iron (Fe²⁺), the absorbable form.

- Duodenal Uptake – Divalent metal transporter‑1 (DMT‑1) on enterocytes transports Fe²⁺ into the cell. Heme iron is taken up via a separate heme carrier protein and then liberated as Fe²⁺ inside the cell.

- Intracellular Storage – Excess iron is stored as ferritin within enterocytes. The amount stored reflects recent dietary intake.

- Export to Plasma – Ferroportin transports iron from enterocytes into the bloodstream, where it binds transferrin.

- Hepatic Storage – The liver sequesters iron as ferritin; serum ferritin mirrors hepatic stores because a small fraction leaks into circulation.

When dietary iron is sufficient, intracellular ferritin levels rise, and consequently, serum ferritin climbs within the normal reference range. Conversely, chronic low intake, increased losses (e.g., menstruation, gastrointestinal bleeding), or malabsorption cause depletion of stores, lowering ferritin well before hemoglobin drops.

Assessing Ferritin in Clinical Practice

Screening Populations – Women of childbearing age, adolescent girls, pregnant women, and athletes are high‑risk groups for low ferritin.

Interpretation Thresholds –

- <12 ng/mL (men) or <15 ng/mL (women) = iron deficiency likely.

- 12‑30 ng/mL (men) or 15‑30 ng/mL (women) = borderline; consider iron studies and clinical symptoms.

- >400 ng/mL (men) or >300 ng/mL (women) = possible iron overload or inflammatory elevation.

Complementary Tests – Serum iron, total iron‑binding capacity (TIBC), transferrin saturation, and CBC provide a fuller picture. Ferritin should be interpreted with C‑reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate when inflammation is suspected.

Dietary Strategies to Optimize Ferritin

For Low Ferritin (Iron Deficiency)

- Prioritize Heme Iron – Include 2‑3 servings of red meat, poultry, or fish per week.

- Combine Non‑Heme Iron with Vitamin C – Example: Lentil soup topped with fresh lemon juice, or a spinach salad with orange segments.

- Reduce Inhibitors During Meals –

- Drink tea/coffee at least 1 hour before or after iron‑rich meals.

- Separate calcium‑rich foods (milk, cheese) from iron sources.

- Use Preparation Techniques – Soak beans for 8‑12 hours, sprout grains, or ferment batter (e.g., dosa) to lower phytate content.

- Consider Iron‑Fortified Products – Breakfast cereals, plant milks, and nutrition bars fortified with elemental iron can provide an additional 5‑10 mg per serving.

For High Ferritin (Potential Overload)

- Limit Red Meat – Reduce intake to ≤2 servings per week; focus on lean poultry and fish.

- Avoid Iron Supplements – Discontinue unless medically directed.

- Increase Phytate‑Rich Foods – Whole grain breads, legumes, and nuts can modestly bind excess iron.

- Consume Antioxidant‑Rich Foods – Berries, nuts, and green tea (in moderation) support liver health, which is critical when iron stores are high.

- Medical Management – Therapeutic phlebotomy or chelation therapy may be necessary for hereditary hemochromatosis; dietary changes are adjunctive.

Supplementation: When Food Alone Is Not Enough

Indications

- Documented iron deficiency anemia (Ferritin <15 ng/mL).

- Pregnancy (especially second and third trimesters) when dietary intake cannot meet the ~27 mg/day requirement.

- Heavy menstrual bleeding, gastrointestinal malabsorption (celiac disease, bariatric surgery), or chronic kidney disease.

Choosing a Supplement

| Form | Elemental Iron Content | Absorption Rate | Common Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ferrous sulfate | 20 % (e.g., 325 mg tablet = 65 mg elemental) | High | Constipation, nausea, dark stools |

| Ferrous gluconate | 12 % (e.g., 300 mg tablet = 36 mg elemental) | Moderate | Less GI upset than sulfate |

| Ferrous fumarate | 33 % (e.g., 200 mg tablet = 66 mg elemental) | High | Similar to sulfate |

| Heme iron polypeptide | 20 % (derived from bovine hemoglobin) | Highest, minimally affected by inhibitors | Generally well tolerated |

| Carbonyl iron | 100 % (pure iron particles) | Slow, steady release | Low GI irritation |

Dosing Recommendations

- Adults with deficiency – 100‑200 mg elemental iron daily, divided into two doses.

- Pregnant women – 27 mg elemental iron per day (often provided by prenatal formulas).

- Children (1‑12 yr) – 7‑15 mg elemental iron daily, based on age and weight.

Maximizing Absorption & Minimizing Side Effects

- Take on an empty stomach (30 minutes before meals) for best absorption; if GI upset occurs, a small amount of food can be added.

- Avoid concurrent calcium, antacids, or high‑phytate foods within 2 hours of the supplement.

- Vitamin C boost – A glass of orange juice or a vitamin C tablet with the iron dose can increase absorption by up to 2‑fold.

- Monitor ferritin – Re‑check serum ferritin after 6‑8 weeks of therapy; adjust dose if ferritin exceeds 150 ng/mL (women) or 300 ng/mL (men).

Potential Risks of Over‑Supplementation

- Gastrointestinal irritation – nausea, constipation, or diarrhea.

- Iron toxicity – Acute ingestion of >20 mg/kg can be fatal, especially in children. Keep supplements out of reach.

- Oxidative stress – Excess free iron can catalyze free‑radical formation; long‑term high ferritin (>400 ng/mL) is linked to metabolic syndrome and liver disease.

Practical Action Plan: From Test to Target Ferritin

| Step | Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Get Tested | Order serum ferritin, CBC, and CRP. | Establish baseline and rule out inflammation. |

| 2. Interpret Results | Compare ferritin to age‑ and gender‑specific ranges. | Identify deficiency, sufficiency, or overload. |

| 3. Dietary Review | Record 3‑day food intake focusing on iron sources and inhibitors. | Pinpoint gaps or excesses. |

| 4. Implement Food Strategies | Add heme iron 2‑3 times/week; pair non‑heme meals with vitamin C; avoid tea/coffee at meals. | Optimize natural iron absorption. |

| 5. Consider Supplementation | If ferritin <15 ng/mL or symptomatic, start appropriate iron supplement. | Rapidly replenish stores. |

| 6. Re‑evaluate | Repeat ferritin after 6‑8 weeks; adjust diet/supplement dose. | Ensure target range is reached without overshoot. |

| 7. Maintenance | Once ferritin is within 30‑150 ng/mL (women) or 30‑400 ng/mL (men), maintain with balanced diet; annual check if risk factors persist. | Prevent recurrence. |

Lifestyle Factors That Influence Ferritin

- Physical Activity – Endurance athletes often develop “sports anemia” due to hemolysis and increased iron loss in sweat; they may require higher dietary iron.

- Weight Management – Obesity is associated with elevated ferritin independent of iron stores because ferritin is an acute‑phase reactant released from adipose tissue. Weight loss can normalize ferritin.

- Alcohol Consumption – Chronic alcohol intake damages the liver, impairing ferritin storage and potentially raising serum ferritin due to inflammation.

- Smoking – Increases oxidative stress and may elevate ferritin as a protective response.

Adopting a balanced lifestyle—regular moderate exercise, weight control, limited alcohol, and smoking cessation—supports optimal iron metabolism and accurate ferritin interpretation.

Special Populations

Pregnancy

- Increased Demand – Total iron requirement rises to ~1 g across pregnancy. Ferritin should stay >30 ng/mL to sustain fetal neurodevelopment.

- Supplementation – Prenatal vitamins usually contain 27 mg elemental iron; additional 10‑20 mg may be needed in women with low baseline ferritin.

Adolescents

- Growth Spurts – Iron needs peak at ages 12‑15 (boys) and 12‑14 (girls). Encourage iron‑rich snacks (e.g., beef jerky, fortified cereal with fruit).

Elderly

- Absorption Decline – Gastric acid production wanes, reducing non‑heme iron absorption. Consider heme iron supplements or vitamin C‑enhanced meals.

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

- Anemia of CKD – Often multifactorial; ferritin may be misleadingly high due to inflammation. Use transferrin saturation and consider intravenous iron when oral therapy fails.

Bottom Line

Ferritin is a window into the body’s iron reserves, and its normal range varies markedly by age, sex, and physiological state. Maintaining ferritin within the appropriate range hinges on a combination of dietary choices, mindful preparation techniques, and, when necessary, targeted supplementation. By regularly monitoring ferritin, optimizing iron‑rich foods, and addressing lifestyle factors, individuals can prevent both iron deficiency and iron overload, supporting overall health and vitality.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of abnormal Ferritin levels?

The most frequent cause of low ferritin is inadequate dietary iron combined with increased losses, such as menstrual bleeding, gastrointestinal bleeding, or rapid growth during adolescence. High ferritin most commonly reflects chronic inflammation, liver disease, or hereditary hemochromatosis, rather than true iron overload alone.

How often should I get my Ferritin tested?

For individuals at risk of deficiency (e.g., women of childbearing age, athletes, pregnant women), testing once annually or whenever symptoms of fatigue, hair loss, or brittle nails appear is reasonable. Those undergoing iron therapy should have ferritin rechecked after 6‑8 weeks to gauge response. People with known iron overload or chronic inflammatory conditions may need semi‑annual monitoring.

Can lifestyle changes improve my Ferritin levels?

Absolutely. Enhancing dietary iron intake, pairing meals with vitamin C, reducing consumption of tea/coffee at meals, and correcting gastrointestinal issues (e.g., H. pylori infection) can raise low ferritin. Conversely, moderating red‑meat intake, maintaining a healthy weight, limiting alcohol, and managing chronic inflammation can help lower excessively high ferritin. Regular physical activity and smoking cessation further support optimal iron metabolism.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Always consult a healthcare professional.