High Ferritin Levels: Causes, Symptoms, and Risks

| Population | Normal Range | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Men | 30‑400 | ng/mL | Upper limit varies by laboratory; values > 300 ng/mL often trigger further evaluation |

| Adult Women (premenopausal) | 15‑150 | ng/mL | Lower end reflects menstrual iron loss |

| Adult Women (postmenopausal) | 30‑200 | ng/mL | Menopause reduces physiologic iron loss |

| Children (1‑5 yr) | 7‑140 | ng/mL | Wide range due to rapid growth |

| Children (6‑12 yr) | 10‑200 | ng/mL | Influenced by diet and infection status |

| Adolescents (13‑18 yr) | 12‑300 | ng/mL | Pubertal growth spurt increases iron demand |

| Pregnant Women | 10‑120 | ng/mL | Hemodilution and fetal iron transfer lower serum ferritin |

Ferritin is the primary intracellular protein that stores iron and releases it in a controlled fashion. Because a small fraction of ferritin circulates in the bloodstream, serum ferritin serves as a practical proxy for total body iron stores. While low ferritin is synonymous with iron‑deficiency anemia, elevated ferritin often signals excess iron or an inflammatory state. Understanding why ferritin rises, how it manifests clinically, and what health threats it poses is essential for clinicians, dietitians, and anyone monitoring their own iron status.

What Is Ferritin and Why Does It Matter?

- Structure & Function – Ferritin is a 24‑subunit protein that can store up to 4,500 iron atoms. It sequesters iron in a non‑reactive form, preventing oxidative damage while providing a readily mobilizable reserve.

- Serum Ferritin – Only about 1 % of total body ferritin is found in plasma. Serum concentrations reflect the balance between iron intake, utilization, and loss.

- Dual Role – Ferritin is also an acute‑phase reactant; its production rises during infection, inflammation, or malignancy independent of iron status. This dual nature makes interpretation challenging but also clinically valuable.

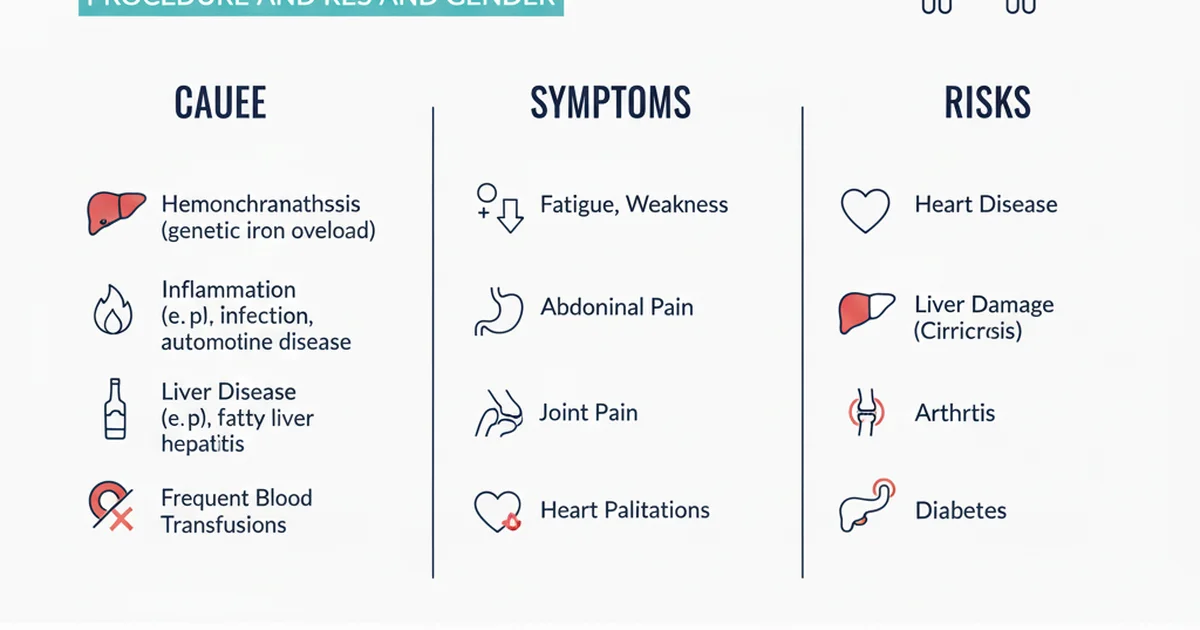

Primary Causes of Elevated Ferritin

1. Iron‑Overload Disorders

| Condition | Pathophysiology | Typical Ferritin Range |

|---|---|---|

| Hereditary Hemochromatosis (HFE mutations) | Increased intestinal iron absorption → progressive organ deposition | > 500 ng/mL, often > 1,000 ng/mL |

| Secondary Hemochromatosis (transfusion‑dependent anemia, thalassemia) | Repeated blood transfusions deliver excess iron | > 1,000 ng/mL |

| Ferroportin disease | Defective iron export from macrophages → intracellular accumulation | Moderately high (300‑800 ng/mL) |

2. Chronic Inflammation & Acute‑Phase Reactivity

- Rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease – Cytokines (IL‑6, TNF‑α) stimulate hepatic ferritin synthesis.

- Infections – Bacterial, viral, or fungal infections raise ferritin as part of the innate immune response.

- Malignancy – Certain cancers (especially liver, lymphoma) produce high ferritin levels, sometimes exceeding 1,000 ng/mL.

3. Liver Disease

- Non‑alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and alcoholic liver disease impair ferritin clearance and increase hepatic synthesis.

- Hepatitis C and cirrhosis are often accompanied by ferritin > 300 ng/mL.

4. Metabolic Syndrome & Insulin Resistance

- Elevated ferritin correlates with visceral adiposity, hypertriglyceridemia, and elevated fasting glucose. It may act both as a marker and a mediator of oxidative stress.

5. Excessive Dietary Iron or Supplementation

- High‑dose oral iron supplements (≥ 100 mg elemental iron daily) can push ferritin above the normal range within weeks.

- Fortified foods (e.g., breakfast cereals) combined with supplement use can unintentionally overload iron‑replete individuals.

6. Other Rare Causes

- Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) – Massive cytokine storm leads to extreme hyperferritinemia (> 10,000 ng/mL).

- Porphyria cutanea tarda – Associated with iron overload and elevated ferritin.

Clinical Symptoms of High Ferritin

Because ferritin itself is not toxic, symptoms arise from iron overload or the underlying disease driving ferritin elevation.

Symptoms Related to Iron Overload

- Fatigue & arthralgia – Iron deposition in joints and muscles causes stiffness and chronic tiredness.

- Skin hyperpigmentation – Excess iron in the dermis leads to bronze‑colored skin.

- Abdominal pain – Hepatomegaly or splenomegaly may be palpable.

- Cardiac manifestations – Dilated cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, or heart failure in advanced disease.

- Endocrine dysfunction – Diabetes mellitus, hypogonadism, or hypothyroidism due to iron‑induced glandular damage.

Symptoms from Inflammation or Liver Disease

- Fever, night sweats, weight loss – Typical of chronic inflammatory or malignant processes.

- Jaundice, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy – Indicate advanced liver pathology.

Important: Many individuals with mildly elevated ferritin are asymptomatic; the value is often discovered incidentally during routine labs.

Risks Associated With Persistent Hyperferritinemia

- Organ Fibrosis – Iron catalyzes the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), promoting fibrosis in the liver, heart, and pancreas.

- Cardiovascular Disease – Elevated ferritin correlates with increased carotid intima‑media thickness and higher risk of myocardial infarction, likely via oxidative lipid damage.

- Insulin Resistance & Type 2 Diabetes – Iron overload impairs insulin signaling and β‑cell function.

- Infection Susceptibility – Pathogens such as Vibrio and Yersinia thrive in iron‑rich environments; high ferritin may predispose to severe infections.

- Malignancy Risk – Chronic oxidative stress contributes to DNA damage; epidemiologic data link high ferritin with liver and colorectal cancers.

Early identification and management can mitigate these sequelae.

Dietary Sources of Iron and Their Influence on Ferritin

| Food Group | Heme Iron (mg/100 g) | Non‑Heme Iron (mg/100 g) | Typical Bioavailability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red meat (beef, lamb) | 2.5‑3.0 | — | 15‑35 % |

| Poultry (dark meat) | 1.0‑1.5 | — | 12‑25 % |

| Fish & shellfish | 0.5‑2.0 | — | 10‑30 % |

| Legumes (lentils, beans) | — | 3‑5 | 2‑20 % (enhanced with vitamin C) |

| Dark leafy greens (spinach, kale) | — | 2‑3 | 2‑10 % (phytate‑bound) |

| Nuts & seeds | — | 1‑3 | 2‑15 % |

| Iron‑fortified cereals | — | 4‑12 | Varies; often 10‑20 % |

Key Points on Bioavailability

- Heme iron (from animal sources) is absorbed via a dedicated transporter and is relatively unaffected by dietary inhibitors.

- Non‑heme iron absorption is modulated by enhancers (vitamin C, meat factor, certain organic acids) and inhibitors (phytates in grains, polyphenols in tea/coffee, calcium).

- Meal composition matters – Consuming vitamin C‑rich foods (citrus, bell peppers) with plant‑based iron can increase non‑heme iron absorption by up to 4‑fold.

- Cooking methods – Soaking, sprouting, or fermenting legumes reduces phytate content, improving iron availability.

Managing Elevated Ferritin Through Nutrition

Foods to Limit

- Excessive red meat & organ meats – These provide high heme iron; moderation helps lower iron intake.

- Iron‑fortified processed foods – Breakfast cereals, energy bars, and some infant formulas can add unnecessary iron.

- Alcohol – Promotes hepatic iron accumulation and impairs ferritin clearance.

Foods to Emphasize

- Polyphenol‑rich beverages (green tea, coffee) – Inhibit iron absorption; useful when taken between meals.

- Calcium‑rich dairy – Calcium competes with iron for transport; a modest intake can blunt iron uptake.

- Phytate‑rich whole grains – When not overly processed, they modestly reduce iron absorption.

Caution: Individuals with anemia or pregnancy require adequate iron; any dietary restriction should be personalized and, when possible, supervised by a healthcare professional.

Supplementation: When Is It Appropriate?

| Situation | Recommended Approach | Monitoring |

|---|---|---|

| Documented iron deficiency (Ferritin < 15 ng/mL) | Oral ferrous sulfate 325 mg (≈ 65 mg elemental iron) once daily; consider alternate formulations if GI intolerance | Re‑check ferritin in 4‑6 weeks; avoid exceeding target range |

| Anemia of chronic disease with low iron stores | Low‑dose iron (e.g., ferrous gluconate 100 mg) only if ferritin < 30 ng/mL and transferrin saturation < 20 % | Monitor inflammatory markers and ferritin quarterly |

| Post‑phlebotomy iron repletion (e.g., after therapeutic venesection) | Short‑term supplementation (30‑60 mg elemental iron) for 2‑4 weeks | Ferritin should rise to 100‑200 ng/mL before stopping |

| No iron deficiency (Ferritin > 150 ng/mL) | Do NOT supplement; supplementation can worsen overload and increase oxidative stress | N/A |

Key safety notes

- Avoid high‑dose iron without indication – Excess iron can cause gastrointestinal distress, oxidative mucosal injury, and long‑term organ damage.

- Chelation therapy (e.g., deferoxamine, deferasirox) is reserved for severe secondary iron overload and must be managed by a specialist.

- Phlebotomy remains the first‑line treatment for hereditary hemochromatosis; typical schedule is 500 mL weekly until ferritin falls below 50 ng/mL, then maintenance every 2‑4 months.

Actionable Steps for Individuals With Elevated Ferritin

- Confirm the cause – Order a complete iron panel (serum iron, total iron‑binding capacity, transferrin saturation) plus inflammatory markers (CRP, ESR) and liver function tests.

- Assess lifestyle factors – Review diet, alcohol intake, supplement use, and family history of hemochromatosis.

- Modify diet – Reduce heme‑iron sources, incorporate iron‑absorption inhibitors between meals, and limit fortified processed foods.

- Address underlying disease – Treat chronic inflammatory conditions, optimize glycemic control in metabolic syndrome, and manage liver disease.

- Consider therapeutic phlebotomy – If iron overload is confirmed and ferritin remains > 300 ng/mL after addressing secondary causes.

- Follow‑up testing – Re‑measure ferritin and transferrin saturation every 3‑6 months initially, then annually once stable.

When to Seek Medical Evaluation

- Ferritin > 500 ng/mL on two separate occasions.

- Presence of symptoms such as unexplained fatigue, joint pain, skin discoloration, or cardiac irregularities.

- Family history of hereditary hemochromatosis or known liver disease.

- Elevated liver enzymes, abnormal glucose tolerance, or unexplained cardiomyopathy.

Early referral to a hematologist, gastroenterologist, or endocrinologist can prevent irreversible organ damage.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of abnormal Ferritin levels?

The most frequent cause of elevated ferritin is chronic inflammation or infection, which drives hepatic production of ferritin as an acute‑phase reactant. In the absence of inflammation, hereditary hemochromatosis is the leading genetic cause of true iron overload.

How often should I get my Ferritin tested?

For individuals with known risk factors (family history of hemochromatosis, chronic liver disease, or metabolic syndrome), testing every 6‑12 months is reasonable. If you are undergoing treatment for iron overload (phlebotomy or chelation), ferritin should be checked every 3 months until target levels are reached, then semi‑annually for maintenance.

Can lifestyle changes improve my Ferritin levels?

Yes. Reducing intake of heme‑iron foods, limiting alcohol, incorporating iron‑absorption inhibitors (tea, coffee, calcium‑rich foods) between meals, and managing underlying inflammatory or metabolic conditions can lower ferritin. Regular aerobic exercise and weight loss also improve insulin sensitivity, which may indirectly reduce iron accumulation.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Always consult a healthcare professional.