Low Ferritin (Iron Deficiency): Symptoms and Treatment

Ferritin is the primary intracellular protein that stores iron and releases it in a controlled fashion. Because ferritin levels reflect the size of the body’s iron reserve, measuring serum ferritin is the most reliable single test for detecting iron deficiency—long before anemia becomes apparent. Low ferritin is a common finding in many populations, especially women of childbearing age, athletes, vegetarians, and individuals with chronic blood loss. This article provides an evidence‑based overview of the physiology of ferritin, the clinical picture of low ferritin, diagnostic considerations, dietary sources, bioavailability, and practical supplementation strategies.

Understanding Ferritin and Iron Homeostasis

What Is Ferritin?

- Structure: A spherical protein complex composed of 24 subunits that can store up to 4,500 iron atoms.

- Location: Predominantly intracellular (liver, spleen, bone marrow, and muscle) with a small fraction circulating in serum.

- Function: Acts as a buffer against iron deficiency and overload, releasing iron when needed for hemoglobin synthesis, mitochondrial respiration, and enzymatic reactions.

How Ferritin Reflects Iron Status

- Serum ferritin correlates with total body iron stores.

- Levels decline early in iron depletion, often before a drop in hemoglobin or hematocrit.

- Acute‑phase reactant: Ferritin rises in inflammation, infection, or liver disease, which can mask iron deficiency; interpreting ferritin in such contexts may require concurrent inflammatory markers (e.g., C‑reactive protein).

Reference Ranges for Serum Ferritin

| Population | Normal Range | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Men | 30‑400 | ng/mL | Upper limit may be higher in some labs |

| Adult Women (premenopausal) | 15‑150 | ng/mL | Lower end reflects menstrual losses |

| Adult Women (postmenopausal) | 30‑200 | ng/mL | Increases after cessation of menses |

| Children (1‑5 y) | 7‑140 | ng/mL | Age‑dependent; rapid growth increases demand |

| Children (6‑12 y) | 10‑200 | ng/mL | |

| Adolescents (13‑18 y) | 12‑300 | ng/mL | Higher in boys than girls |

| Pregnancy (first trimester) | 12‑150 | ng/mL | Physiologic dilution lowers values |

| Pregnancy (second/third trimester) | 10‑120 | ng/mL | Higher iron demands for fetal development |

Reference ranges can vary between laboratories; always interpret results in the context of the specific assay used.

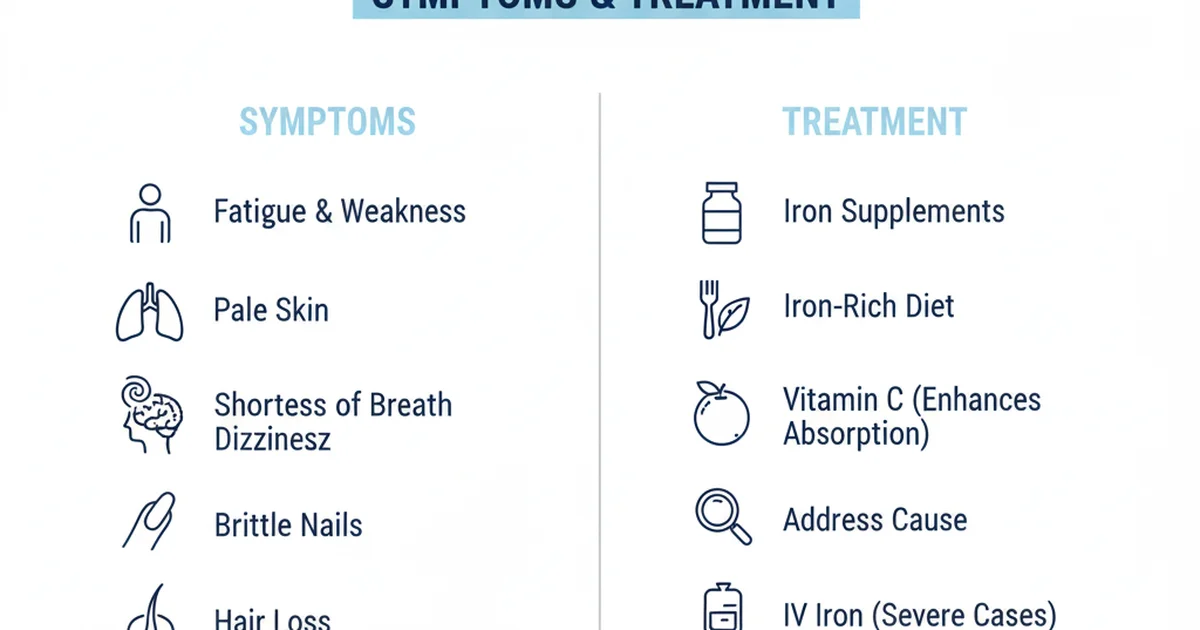

Clinical Presentation of Low Ferritin

Common Symptoms

- Fatigue and decreased exercise tolerance – the brain and muscles receive less oxygen due to reduced hemoglobin synthesis.

- Pallor (skin, conjunctiva) – visible when anemia progresses.

- Hair loss and brittle nails – iron is essential for keratin formation.

- Restless legs syndrome – linked to iron deficiency in the central nervous system.

- Pica (craving non‑nutritive substances) – classic but uncommon.

- Glossitis and angular cheilitis – inflamed tongue and mouth corners.

- Cold intolerance – reduced thermogenesis.

When to Suspect Low Ferritin Without Anemia

- Persistent low‑grade fatigue despite adequate sleep.

- Decreased cognitive performance or difficulty concentrating.

- Recurrent infections (iron is needed for immune cell proliferation).

Causes of Low Ferritin

| Category | Typical Etiologies |

|---|---|

| Dietary Insufficiency | Vegan/vegetarian diets lacking heme iron, low‑iron foods, restrictive eating patterns, poor overall nutrition. |

| Increased Physiologic Demand | Pregnancy, adolescence, endurance training, chronic kidney disease (erythropoietin therapy). |

| Blood Loss | Menstruation (heavy or prolonged), gastrointestinal bleeding (ulcers, hemorrhoids, malignancy, NSAID use), regular blood donation. |

| Malabsorption | Celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, bariatric surgery, Helicobacter pylori infection. |

| Chronic Inflammation | Elevated ferritin due to acute‑phase response can mask low iron; functional iron deficiency may coexist. |

| Genetic Conditions | Iron‑refractory iron deficiency anemia (IRIDA), hereditary hemochromatosis (paradoxically can present with low ferritin after phlebotomy). |

Diagnostic Evaluation

- Serum Ferritin – first‑line test; < 30 ng/mL in most adults strongly suggests iron deficiency.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) – look for microcytic, hypochromic anemia (low MCV, low MCH).

- Serum Iron, Total Iron‑Binding Capacity (TIBC), Transferrin Saturation – help differentiate iron deficiency from anemia of chronic disease.

- Peripheral Blood Smear – may show anisocytosis, poikilocytosis, and pencil‑shaped erythrocytes.

- Inflammatory Markers – CRP or ESR if ferritin is borderline; high CRP can falsely elevate ferritin.

- Stool Occult Blood Test – for occult gastrointestinal bleeding in adults with unexplained low ferritin.

- Upper/Lower Endoscopy – indicated when GI blood loss is suspected and non‑invasive tests are positive.

Dietary Sources of Iron

Heme Iron (Highly Bioavailable)

| Food | Approx. Iron Content (mg per 100 g) |

|---|---|

| Beef liver | 6.5 |

| Chicken liver | 9.0 |

| Lean beef (sirloin) | 2.6 |

| Pork (loin) | 1.2 |

| Lamb | 1.7 |

| Fish (sardines, canned with bones) | 2.9 |

Heme iron absorption rates 15‑35 % and are less affected by dietary inhibitors.

Non‑Heme Iron (Variable Bioavailability)

| Food | Approx. Iron Content (mg per 100 g) |

|---|---|

| Lentils (cooked) | 3.3 |

| Chickpeas (cooked) | 2.9 |

| Tofu (firm) | 5.4 |

| Spinach (cooked) | 3.6 |

| Pumpkin seeds | 3.3 |

| Quinoa (cooked) | 1.5 |

| Fortified breakfast cereals | 4‑18 (varies) |

Non‑heme iron absorption is 2‑20 % and heavily influenced by enhancers and inhibitors.

Factors Influencing Iron Bioavailability

Enhancers

- Vitamin C (ascorbic acid): Reduces ferric (Fe³⁺) to ferrous (Fe²⁺) form, markedly increasing non‑heme iron absorption. One cup of orange juice with a meal can boost absorption by up to 4‑fold.

- Meat, fish, poultry (MFP factor): Amino acids and peptides from animal protein enhance non‑heme iron uptake.

- Organic acids (citric, lactic) found in fermented foods also aid absorption.

Inhibitors

- Phytates (found in whole grains, legumes, nuts, seeds) bind iron; soaking, sprouting, or fermenting reduces phytate content.

- Polyphenols (tea, coffee, cocoa) chelate iron; avoid drinking these beverages with iron‑rich meals.

- Calcium (dairy, supplements) competes for absorption sites; separate calcium intake from iron‑rich meals by at least 2 hours.

- Soy proteins (especially isolated soy) can modestly inhibit iron uptake.

Practical Meal‑Planning Tips

- Pair iron‑rich plant foods with vitamin C sources (e.g., lentil soup with bell peppers, spinach salad with strawberries).

- Include a small serving of meat or fish when possible to leverage the MFP factor.

- Soak or sprout beans, grains, and seeds before cooking to lower phytate levels.

- Avoid tea/coffee within 30 minutes before or after iron‑containing meals.

- Space calcium‑rich foods (milk, cheese) away from iron sources.

Treatment Strategies

1. Dietary Modification

- Goal: Increase net iron absorption by 2‑3 mg/day through food choices and timing.

- Actionable Steps

- Add 2‑3 servings of heme iron per week (e.g., lean beef, poultry, fish).

- Incorporate non‑heme iron foods at every main meal (legumes, dark leafy greens, fortified grains).

- Combine each iron‑rich item with a vitamin C source (citrus, kiwi, tomatoes, bell peppers).

- Limit phytate‑rich foods in the same meal; if consuming them, pre‑process (soak, ferment).

- Schedule calcium intake separate from iron‑rich meals.

2. Oral Iron Supplementation

| Form | Typical Dose | Absorption % | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferrous sulfate | 325 mg (≈65 mg elemental Fe) once daily | 10‑20 % | Inexpensive, widely available | GI upset (nausea, constipation) |

| Ferrous gluconate | 240 mg (≈35 mg elemental Fe) | 10‑15 % | Slightly better tolerability | More tablets needed |

| Ferrous fumarate | 300 mg (≈106 mg elemental Fe) | 15‑20 % | High elemental iron per tablet | GI irritation possible |

| Iron polymaltose complex (IPC) | 100 mg elemental Fe | 20‑30 % | Low GI side effects, good for sensitive patients | Higher cost |

| Heme iron polypeptide (Proferrin) | 12 mg elemental Fe | 20‑30 % | Better tolerated, less interaction with food | Expensive, limited availability |

Key Recommendations

- Start with low‑dose elemental iron (30‑60 mg) taken on an empty stomach with a small amount of vitamin C (e.g., orange juice).

- If GI intolerance occurs, take with a light snack (e.g., toast) and consider a slow‑release or polymer‑bound preparation.

- Avoid concurrent calcium, antacids, or high‑fiber meals for at least 2 hours.

- Continue supplementation for 3–6 months after ferritin normalizes to replenish stores fully.

3. Intravenous (IV) Iron

Indicated when:

- Oral iron is poorly tolerated or ineffective after 4‑6 weeks.

- Rapid repletion is required (e.g., severe anemia, pre‑operative optimization, pregnancy with severe deficiency).

- Malabsorption syndromes (post‑bariatric surgery, IBD) limit oral uptake.

Common IV preparations

- Ferric carboxymaltose – up to 1 g in a single infusion; low risk of anaphylaxis.

- Iron sucrose – 200‑300 mg per session; requires multiple visits.

- Low‑molecular‑weight iron dextran – larger total doses but higher risk of hypersensitivity.

Safety considerations

- Screen for active infections and iron overload disorders before infusion.

- Monitor serum ferritin and transferrin saturation 2‑4 weeks post‑infusion to avoid excess iron.

4. Monitoring and Follow‑Up

| Parameter | Timing | Target |

|---|---|---|

| Serum Ferritin | Baseline, 4‑6 weeks, then every 3 months until stable | ≥ 30 ng/mL (men) / ≥ 15 ng/mL (women) |

| Hemoglobin | Baseline, every 4 weeks during treatment | ≥ 13 g/dL (men) / ≥ 12 g/dL (women) |

| Transferrin Saturation | Baseline, after 8 weeks of therapy | 20‑50 % |

| CRP (if inflammation suspected) | Baseline, repeat if ferritin remains low despite iron therapy | < 5 mg/L |

If ferritin fails to rise after 8‑12 weeks of appropriate oral therapy, reassess for malabsorption, ongoing blood loss, or chronic inflammation.

Special Populations

Women of Reproductive Age

- Menstrual losses can range from 30‑80 mL per cycle; heavy menstrual bleeding (> 80 mL) often drives ferritin < 15 ng/mL.

- Contraceptive choice: Hormonal IUDs can reduce menstrual blood loss and improve iron status.

Athletes

- Exercise‑induced hemolysis and sweat losses increase iron demand.

- Training schedule: Time iron supplementation on rest days or after training sessions to maximize absorption.

Children & Adolescents

- Rapid growth spikes elevate iron requirements; school‑age children need ~ 7‑10 mg elemental iron/day.

- Encourage iron‑rich snacks (e.g., fortified cereal with fruit) and limit excessive cow’s milk (high calcium, low iron).

Elderly

- Decreased gastric acid production reduces non‑heme iron solubility; consider ferrous sulfate with a small amount of vitamin C or IV iron if oral therapy fails.

Lifestyle Strategies to Support Ferritin Recovery

- Regular physical activity improves circulation and can stimulate erythropoiesis, but avoid excessive endurance training without adequate nutrition.

- Stress management: Chronic stress can elevate cortisol, which may impair iron metabolism. Mind‑body practices (yoga, meditation) are beneficial.

- Adequate sleep: Sleep deprivation interferes with hormonal regulation of iron absorption (e.g., hepcidin). Aim for 7‑9 hours/night.

- Avoid smoking: Carbon monoxide reduces oxygen delivery, increasing the body’s demand for functional hemoglobin.

Putting It All Together: A Step‑by‑Step Action Plan

- Confirm low ferritin with a laboratory test and assess for anemia.

- Identify underlying cause (dietary, menstrual, GI loss, malabsorption).

- Implement dietary changes immediately: add heme iron, pair with vitamin C, separate calcium.

- Start oral iron (ferrous sulfate 325 mg every other day) while monitoring GI tolerance.

- Re‑evaluate in 4‑6 weeks: if ferritin rises ≥ 30 ng/mL, continue for another 3 months; if not, explore IV iron or address malabsorption.

- Maintain iron stores with periodic ferritin checks (every 6‑12 months) and a balanced diet rich in iron and vitamin C.

Conclusion

Low ferritin is a silent but treatable indicator of depleted iron stores. By understanding the physiology of ferritin, recognizing early symptoms, and applying targeted dietary and supplemental strategies, individuals can restore optimal iron status and prevent progression to anemia. Personalized care—considering gender, age, activity level, and comorbidities—ensures effective treatment while minimizing side effects. Regular monitoring and lifestyle support solidify long‑term iron health, enabling better energy, cognition, and overall well‑being.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of abnormal Ferritin levels?

The most frequent cause of low ferritin is iron deficiency due to inadequate intake or chronic blood loss, with heavy menstrual bleeding and gastrointestinal bleeding being the leading contributors in adults. In contrast, high ferritin often reflects inflammation, liver disease, or iron overload disorders.

How often should I get my Ferritin tested?

For individuals undergoing treatment for iron deficiency, measure ferritin at baseline, then every 4‑6 weeks until levels normalize, followed by a check 3 months after completion to ensure stores are maintained. In stable, asymptomatic individuals, a annual ferritin is reasonable, especially for women of childbearing age, athletes, or those with known risk factors.

Can lifestyle changes improve my Ferritin levels?

Yes. Optimizing diet (adding heme iron, vitamin C, and reducing inhibitors), spacing calcium intake, and addressing sources of chronic blood loss (e.g., treating heavy periods) are foundational. Regular, moderate exercise, adequate sleep, stress reduction, and avoiding smoking further support iron metabolism and help maintain healthy ferritin levels.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Always consult a healthcare professional.