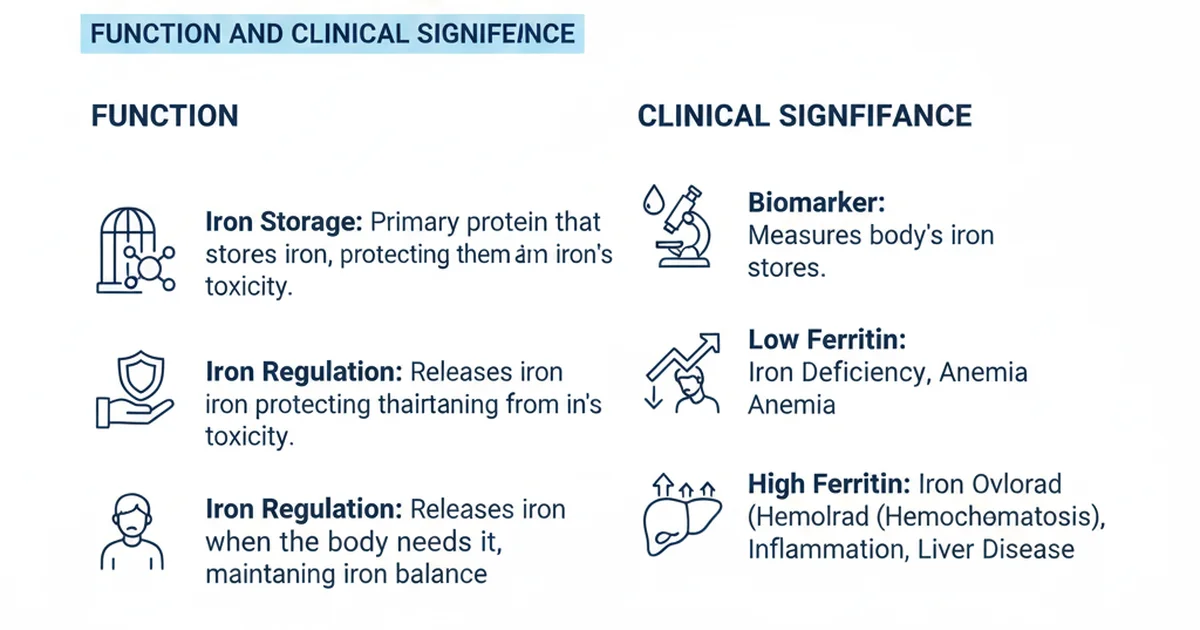

What is Ferritin? Function and Clinical Significance

Ferritin is a protein complex that stores iron within cells and releases it in a controlled fashion. Although the molecule itself is intracellular, a small fraction circulates in the blood and serves as the most reliable laboratory marker of total body iron stores. Understanding ferritin’s role, how to interpret its levels, and how diet, bioavailability, and supplementation influence it is essential for preventing and managing iron‑related disorders such as anemia, fatigue, and chronic disease.

Overview of Ferritin Biology

Structure and Function

- Protein Shell: Ferritin consists of 24 subunits that form a nanocage capable of holding up to 4,500 iron atoms in a mineralized, non‑reactive form.

- Storage Site: It is the primary intracellular iron reservoir in the liver, spleen, bone marrow, and even in the heart and brain.

- Release Mechanism: When the body needs iron—for erythropoiesis, mitochondrial respiration, or enzyme synthesis—ferritin releases iron through a reductive process that maintains iron in a safe, soluble state.

Clinical Relevance

- Serum Ferritin reflects the size of the body’s iron store more accurately than serum iron or total iron‑binding capacity (TIBC).

- Acute‑Phase Reactant: Ferritin rises in inflammation, infection, liver disease, and malignancy, which can mask true iron deficiency.

- Diagnostic Cornerstone: Low ferritin is the earliest laboratory sign of iron deficiency, while markedly high ferritin suggests iron overload, chronic inflammatory states, or storage diseases (e.g., hemochromatosis).

Reference Ranges for Serum Ferritin

| Population | Normal Range | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Men | 30‑400 | ng/mL | Upper limit may be lower in some labs |

| Adult Women | 15‑150 | ng/mL | Lower in premenopausal women |

| Pregnant Women | 10‑70 | ng/mL | Adjusted for gestational age |

| Children (1‑5 yr) | 7‑140 | ng/mL | Age‑dependent; rapid growth influences demand |

| Children (6‑12 yr) | 10‑200 | ng/mL | Slightly higher as iron needs increase |

| Adolescents (13‑18) | 12‑300 | ng/mL | Pubertal growth spurt raises requirements |

| Elderly (>65 yr) | 30‑300 | ng/mL | Inflammatory conditions may elevate values |

Values may vary slightly between laboratories; always interpret results in the context of clinical presentation and other iron studies.

Dietary Sources of Iron and Their Impact on Ferritin

Heme vs. Non‑Heme Iron

| Source Type | Typical Foods | % of Dietary Iron | Absorption Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heme Iron | Red meat, poultry, fish, organ meats | 10‑15% | 15‑35% (highly bioavailable) |

| Non‑Heme Iron | Legumes, nuts, seeds, whole grains, fortified cereals, leafy greens | 85‑90% | 2‑20% (variable) |

- Heme iron is absorbed via a dedicated transporter that is largely unaffected by dietary inhibitors.

- Non‑heme iron absorption is modulated by enhancers (vitamin C, meat factor, certain amino acids) and inhibitors (phytates, polyphenols, calcium).

Key Food Groups

- Red Meat & Poultry – Beef, lamb, turkey, and chicken provide the most bioavailable iron per gram.

- Seafood – Shellfish (clams, oysters, mussels) are exceptionally rich in heme iron; sardines and salmon also contribute.

- Legumes – Lentils, chickpeas, and black beans are excellent plant‑based sources but benefit from cooking methods that reduce phytate content (soaking, sprouting).

- Dark Leafy Greens – Spinach, kale, and collard greens contain iron bound to oxalates; pairing with vitamin C improves uptake.

- Fortified Products – Breakfast cereals, plant milks, and breads often have iron added in a highly soluble form, making them valuable for vegetarians.

Enhancing Non‑Heme Iron Bioavailability

- Vitamin C: Consuming 50‑100 mg of vitamin C (e.g., citrus juice, strawberries, bell peppers) with a non‑heme iron meal can double absorption.

- Meat Factor: Small amounts of animal protein (≈30 g) boost non‑heme iron uptake via an unknown peptide-mediated mechanism.

- Cooking Techniques: Using cast‑iron cookware can leach additional iron into foods, especially acidic dishes like tomato sauces.

Inhibitors to Watch

- Phytates: Present in whole grains, legumes, nuts; soaking, fermenting, or sprouting reduces their inhibitory effect.

- Polyphenols: Found in tea, coffee, red wine; consuming these beverages 30‑60 minutes after meals minimizes interference.

- Calcium: High calcium doses (≥300 mg) can compete with iron for absorption; separate calcium‑rich foods or supplements from iron‑rich meals.

How Ferritin Levels Respond to Diet

- Adequate Iron Intake (≈8 mg/day for adult men, 18 mg/day for premenopausal women) generally maintains ferritin within the normal range.

- Low‑Iron Diet (vegetarian or vegan diets without fortified foods) can gradually deplete ferritin, especially in women with menstrual losses.

- High‑Iron Diet or excessive supplementation may raise ferritin, but the body tightly regulates absorption; only a minority of individuals (e.g., those with hereditary hemochromatosis) develop iron overload from diet alone.

Clinical Significance of Abnormal Ferritin

Low Ferritin (<15 ng/mL)

- Indicates Iron Deficiency: The first laboratory sign, often preceding anemia.

- Symptoms: Fatigue, restless legs, pica, hair loss, decreased exercise tolerance, impaired cognition.

- Risk Groups: Premenopausal women, pregnant women, infants, athletes with high sweat losses, individuals on restrictive diets.

Normal‑Low Ferritin (15‑30 ng/mL)

- May represent early depletion where iron stores are dwindling but not yet deficient.

- Consider evaluating dietary intake, menstrual losses, and inflammatory markers.

Elevated Ferritin (>300 ng/mL in men, >200 ng/mL in women)

- Iron Overload: Hereditary hemochromatosis, repeated transfusions, excessive supplementation.

- Acute‑Phase Reaction: Chronic inflammation (rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease), infection, liver disease, malignancy.

- Metabolic Syndrome: Elevated ferritin correlates with insulin resistance and cardiovascular risk.

Interpreting Ferritin in Inflammation

- When C‑reactive protein (CRP) or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is elevated, ferritin may be falsely high.

- Adjusted Approach: Combine ferritin with transferrin saturation (TSAT) and soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR) to differentiate true iron overload from inflammatory elevation.

Assessment Strategy

- History & Physical – Evaluate dietary patterns, menstrual history, gastrointestinal symptoms, family history of iron disorders.

- Laboratory Panel – Ferritin, serum iron, TIBC, TSAT, complete blood count (CBC), CRP/ESR.

- Follow‑Up – Repeat ferritin after 4‑8 weeks of dietary modification or supplementation to gauge response.

Ferritin Supplementation: When and How

Indications

- Documented iron deficiency (Ferritin <15 ng/mL) with or without anemia.

- Symptomatic low ferritin in athletes, pregnant women, or individuals with high physiological demand.

Forms of Iron Supplements

| Form | Typical Dose (elemental Fe) | Absorption Characteristics | Common Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ferrous Sulfate | 325 mg (≈65 mg elemental) | Highest bioavailability; best with empty stomach | Constipation, nausea, dark stools |

| Ferrous Gluconate | 240 mg (≈35 mg elemental) | Slightly lower absorption; better tolerated | Mild GI upset |

| Ferrous Fumarate | 300 mg (≈106 mg elemental) | High elemental iron; similar to sulfate | GI irritation |

| Iron Polysaccharide Complex | 100 mg (≈30 mg elemental) | Controlled release; less interaction with food | Fewer GI symptoms |

| Heme Iron Polypeptide | 12 mg (≈12 mg elemental) | Highly bioavailable, less affected by inhibitors | Minimal GI upset |

Dosing Recommendations

- Standard Regimen: 100‑200 mg elemental iron daily in divided doses (e.g., 50 mg twice daily).

- Loading Phase: Some clinicians prescribe 200‑300 mg elemental iron for 2‑3 weeks to rapidly replenish stores, then reduce to a maintenance dose of 50‑100 mg daily.

- Duration: Continue supplementation for 3‑6 months after ferritin normalizes to refill intracellular stores fully.

Enhancing Tolerability

- Take iron with vitamin C (e.g., a glass of orange juice) to improve absorption.

- If GI upset occurs, split the dose into smaller portions throughout the day or switch to a gentler formulation (e.g., polysaccharide complex).

- Avoid taking iron with calcium‑rich foods, tea, coffee, or antacids within two hours of the dose.

Monitoring

- Recheck ferritin and CBC 4–8 weeks after initiating therapy.

- If ferritin rises above the target range and side effects persist, consider reducing the dose or switching to intermittent dosing (e.g., every other day).

Lifestyle Strategies to Optimize Ferritin

- Balanced Diet – Incorporate both heme and non‑heme iron sources daily; pair plant‑based iron with vitamin C‑rich foods.

- Meal Timing – Schedule iron‑rich meals separate from calcium‑dense foods and polyphenol‑heavy beverages.

- Cooking Methods – Use cast‑iron cookware for acidic dishes; soak, sprout, or ferment grains and legumes.

- Regular Screening – High‑risk groups (women of reproductive age, athletes, chronic disease patients) should have ferritin checked at least annually.

- Manage Inflammation – Address chronic inflammatory conditions through diet, exercise, and appropriate medical therapy to prevent ferritin elevation unrelated to iron overload.

Actionable Take‑Home Checklist

- Assess: If you experience unexplained fatigue, schedule a ferritin test along with CBC and CRP.

- Diet: Aim for 1–2 servings of heme iron weekly; add a vitamin C source to every non‑heme iron meal.

- Supplement: Use ferrous sulfate 65 mg elemental iron daily for 3 months if ferritin <15 ng/mL, then re‑test.

- Monitor: Repeat ferritin after 6 weeks; adjust dose if ferritin exceeds 150 ng/mL (men) or 100 ng/mL (women).

- Lifestyle: Separate coffee/tea from meals, limit calcium supplements around iron intake, and use cast‑iron pans when possible.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of abnormal Ferritin levels?

The most frequent cause of low ferritin is insufficient dietary iron combined with increased physiological losses, such as menstrual bleeding, pregnancy, or gastrointestinal blood loss. Conversely, high ferritin most often reflects an acute‑phase response to inflammation, infection, or chronic disease rather than true iron overload.

How often should I get my Ferritin tested?

For individuals at risk of iron deficiency (e.g., premenopausal women, pregnant women, athletes, or people on restrictive diets), testing once a year is reasonable. If you are being treated for iron deficiency, re‑check ferritin 4‑8 weeks after starting supplementation and again after completing the course to confirm restoration of stores.

Can lifestyle changes improve my Ferritin levels?

Yes. Optimizing iron intake through heme and enhanced non‑heme sources, pairing iron‑rich foods with vitamin C, reducing intake of inhibitors (phytates, polyphenols, calcium) around meals, and using cast‑iron cookware can all raise ferritin naturally. Managing chronic inflammation through diet, exercise, and appropriate medical therapy also helps keep ferritin in the appropriate range.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Always consult a healthcare professional.