TIBC vs. Transferrin: Key Differences Explained

Reference Ranges for Total Iron Binding Capacity (TIBC)

| Population | Normal Range | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Men | 250‑450 | µg/dL | Slightly higher on average |

| Adult Women (premenopausal) | 250‑460 | µg/dL | Influenced by menstrual blood loss |

| Adult Women (post‑menopausal) | 250‑430 | µg/dL | Values converge with men |

| Children (1‑12 yr) | 300‑560 | µg/dL | Age‑dependent; higher in early childhood |

| Adolescents (13‑18 yr) | 260‑460 | µg/dL | Pubertal hormonal changes affect iron metabolism |

| Pregnancy (2nd trimester) | 300‑600 | µg/dL | Expansion of plasma volume raises TIBC |

| Elderly (≥65 yr) | 250‑440 | µg/dL | May decline modestly with age |

Values represent typical laboratory ranges; individual labs may report slightly different cut‑offs.

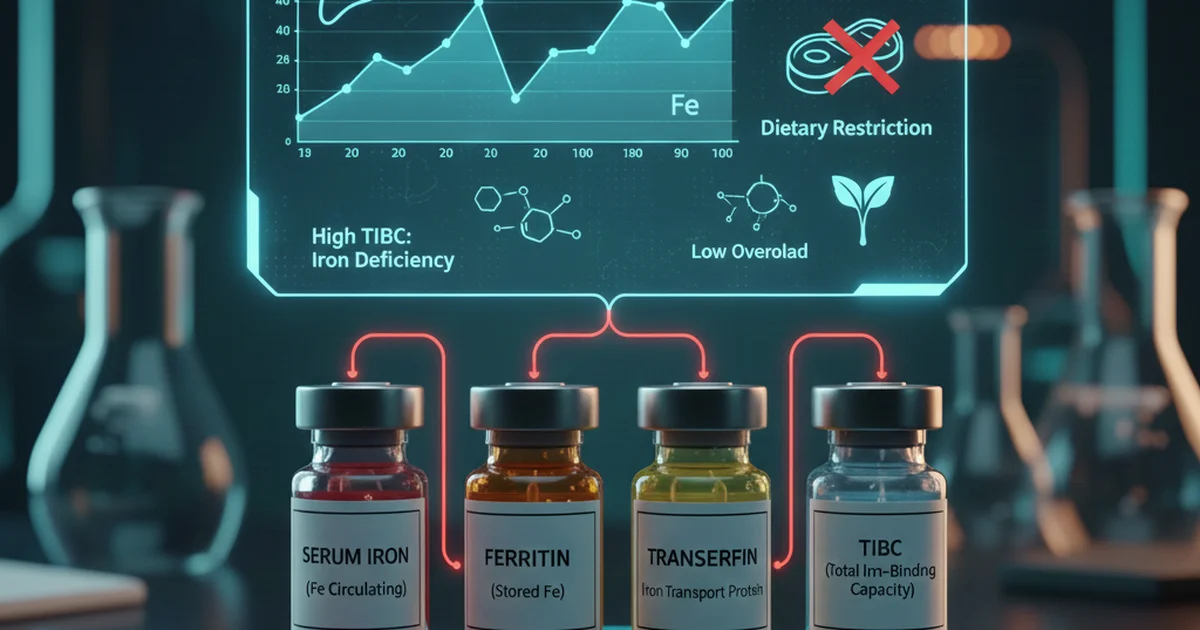

Introduction

Iron is a cornerstone mineral for oxygen transport, DNA synthesis, and cellular respiration. When clinicians suspect iron deficiency or overload, they often order a panel that includes Serum Iron, Ferritin, Transferrin Saturation, and Total Iron Binding Capacity (TIBC). Although TIBC and transferrin are closely related, they measure different aspects of iron physiology. Understanding their distinctions—and how diet, bioavailability, and supplementation influence them—empowers patients and health‑care providers to interpret results accurately and to implement effective nutritional strategies.

What Is Total Iron Binding Capacity (TIBC)?

Definition

TIBC quantifies the maximum amount of iron that can be bound by plasma proteins, primarily transferrin, under standardized laboratory conditions. It reflects the total transport capacity of the blood for iron.

How the Test Is Performed

- Serum sample is mixed with an excess of iron.

- The iron that binds to transferrin is measured.

- Unbound iron is removed, and the bound fraction is quantified.

- The result is expressed as µg/dL (or µmol/L) of iron‑binding sites.

Clinical Meaning

- High TIBC suggests a relative shortage of iron (e.g., iron‑deficiency anemia) because the liver produces more transferrin to capture any available iron.

- Low TIBC can indicate iron overload, chronic inflammation, malnutrition, or liver disease where transferrin synthesis is suppressed.

Key point: TIBC is an indirect marker of transferrin concentration, but it also incorporates the functional binding capacity of the protein.

What Is Transferrin?

Definition

Transferrin is a glycoprotein synthesized by the liver that transports iron from absorption sites (duodenum) to storage sites (bone marrow, liver, spleen). Each transferrin molecule can bind two Fe³⁺ ions.

Measured Parameter

- Serum Transferrin Level: Direct quantification of the protein concentration (mg/dL).

- Transferrin Saturation (TSAT): Ratio of serum iron to TIBC, expressed as a percentage, indicating how much of transferrin’s binding sites are occupied.

Clinical Meaning

- Elevated transferrin typically mirrors an iron‑deficient state (the body attempts to increase transport capacity).

- Reduced transferrin is seen in malnutrition, chronic liver disease, or inflammatory states where hepatic protein synthesis is down‑regulated.

Key Differences Between TIBC and Transferrin

| Feature | TIBC | Transferrin |

|---|---|---|

| What it measures | Functional iron‑binding capacity of all plasma proteins (mostly transferrin) | Concentration of the transferrin protein itself |

| Units | µg/dL (iron equivalents) | mg/dL (protein mass) |

| Interpretation focus | Capacity to bind iron; rises when iron is low | Amount of carrier protein; falls with liver dysfunction |

| Influencing factors | Iron status, liver synthetic function, inflammation | Liver health, protein‑energy malnutrition, hormonal status |

| Clinical use | Part of iron panel to differentiate deficiency vs. overload | Used to calculate TSAT and assess protein synthesis capacity |

| Response to supplementation | Decreases as iron stores improve (binding capacity needed less) | May gradually normalize as iron status stabilizes, but changes are slower |

Bottom line: While TIBC reflects how much iron the blood could carry, transferrin tells us how much of the carrier protein is present. Both rise in iron deficiency but for different mechanistic reasons.

Dietary Sources That Influence TIBC

Because TIBC is primarily driven by iron availability, dietary iron intake—both heme and non‑heme—directly impacts the test.

Heme Iron (Highly Bioavailable)

| Food | Approx. Iron Content (mg per 100 g) |

|---|---|

| Beef liver | 6.5 |

| Chicken thigh (dark meat) | 2.0 |

| Salmon | 0.9 |

| Pork loin | 1.2 |

- Absorption rate: 15‑35 % (unaffected by most dietary inhibitors).

- Effect on TIBC: Regular consumption of heme iron lowers TIBC by raising serum iron and ferritin.

Non‑Heme Iron (Moderate Bioavailability)

| Food | Approx. Iron Content (mg per 100 g) |

|---|---|

| Lentils (cooked) | 3.3 |

| Spinach (cooked) | 3.6 |

| Tofu (firm) | 2.7 |

| Fortified cereals | 4‑18 (varies by brand) |

- Absorption rate: 2‑20 % and highly sensitive to enhancers (vitamin C, meat factor) and inhibitors (phytates, polyphenols, calcium).

- Effect on TIBC: Adequate intake of non‑heme iron, especially when paired with enhancers, can modestly reduce TIBC.

Iron‑Enhancing Nutrients

- Vitamin C (ascorbic acid): Reduces ferric (Fe³⁺) to ferrous (Fe²⁺), increasing non‑heme iron absorption by up to 3‑fold. Citrus fruits, strawberries, bell peppers are excellent sources.

- Meat factor: Amino acids and peptides in meat, fish, poultry improve non‑heme iron uptake; even small amounts (30 g) can boost absorption.

Iron‑Inhibiting Compounds

- Phytates: Found in whole grains, legumes, nuts; bind iron and limit absorption. Soaking, sprouting, or fermenting can reduce phytate content.

- Polyphenols: Tea, coffee, red wine; tannins chelate iron. Consuming these beverages between meals rather than with iron‑rich foods mitigates the effect.

- Calcium: High calcium doses (≥300 mg) can transiently impede both heme and non‑heme iron absorption. Dairy or calcium supplements should be spaced away from iron‑rich meals.

Bioavailability: From Food to TIBC

- Ingestion → gastric acid solubilizes iron.

- Duodenal uptake via DMT1 (divalent metal transporter 1) for Fe²⁺; heme iron uses a separate carrier (HCP1).

- Transport → iron binds to transferrin in the portal circulation.

- Storage & Utilization → iron is deposited in ferritin or used for erythropoiesis.

- Feedback Loop → Low iron triggers hepatic up‑regulation of transferrin synthesis → TIBC rises; high iron suppresses this response → TIBC falls.

Practical implication: Even with adequate iron intake, poor gastric acidity (e.g., long‑term PPIs) or intestinal disorders (celiac disease, IBD) can blunt absorption, causing persistently high TIBC despite dietary effort.

Supplementation Strategies to Optimize TIBC

When to Supplement

- Documented iron deficiency (low ferritin, low serum iron, high TIBC).

- Symptoms of anemia (fatigue, pallor, dyspnea) with supporting labs.

- Pregnancy or growth spurts where iron demand outpaces intake.

Types of Iron Supplements

| Form | Typical Dose | Absorption Efficiency | Common Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ferrous sulfate | 325 mg (≈65 mg elemental Fe) | 15‑35 % | Constipation, nausea, dark stools |

| Ferrous gluconate | 240 mg (≈35 mg elemental Fe) | 12‑20 % | Generally milder GI upset |

| Ferrous fumarate | 300 mg (≈106 mg elemental Fe) | 20‑30 % | Similar to sulfate but may be better tolerated |

| Iron polysaccharide complex | 100 mg (≈50 mg elemental Fe) | 10‑15 % | Low GI irritation, good for sensitive stomachs |

| Heme iron polypeptide | 12 mg elemental Fe | 25‑30 % | Minimal effect of dietary inhibitors |

Evidence‑based tip: Starting with a lower dose (e.g., 30 mg elemental iron) and titrating up reduces gastrointestinal discomfort while still permitting a gradual decline in TIBC over 4‑6 weeks.

Timing and Co‑factors

- Take iron on an empty stomach (30 min before meals) for maximal absorption.

- Pair with vitamin C (e.g., a glass of orange juice) to enhance uptake.

- Avoid calcium, antacids, tea, coffee, and high‑fiber foods within 2 hours of the dose.

- Split doses (e.g., 2×30 mg) if high single doses cause GI upset; absorption is not linear, so splitting can improve total iron uptake.

Monitoring Progress

- Re‑check TIBC, serum iron, and ferritin after 4‑6 weeks of therapy.

- Expect TIBC to decrease by 10‑20 % as iron stores replenish.

- If TIBC remains elevated despite adherence, evaluate for malabsorption or chronic blood loss.

Lifestyle Factors That Influence TIBC

| Factor | Effect on TIBC | Practical Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Regular aerobic exercise | May modestly increase iron turnover, potentially raising TIBC in athletes with high demand | Ensure adequate iron intake, especially for endurance athletes |

| Chronic inflammation (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis) | Elevates hepcidin, reduces iron release, can paradoxically lower TIBC despite low iron availability | Manage underlying inflammation; consider ferritin interpretation with caution |

| Alcohol consumption | Excessive intake impairs liver synthesis, decreasing transferrin and thus TIBC | Limit to moderate levels; monitor liver function |

| Smoking | Increases oxidative stress, may raise serum ferritin (acute‑phase) while lowering TIBC | Smoking cessation improves overall iron metabolism |

| Weight loss diets (very low calorie) | May reduce hepatic protein synthesis → lower transferrin/TIBC | Include adequate protein and iron‑rich foods during caloric restriction |

Actionable Advice for Patients

Assess Dietary Iron

- Aim for 2‑3 servings of heme iron per week (e.g., lean beef, poultry, fish).

- Include non‑heme sources daily, paired with vitamin C‑rich foods.

Optimize Meal Timing

- Schedule iron‑rich meals away from calcium‑dense foods and polyphenol‑rich beverages.

Consider Supplementation When Needed

- Start with a low‑dose ferrous gluconate if gastrointestinal tolerance is a concern.

- Use vitamin C (e.g., 250 mg ascorbic acid) to boost absorption.

Monitor Labs Strategically

- Baseline TIBC, serum iron, ferritin, and TSAT.

- Re‑evaluate after 4–6 weeks of intervention.

Address Underlying Causes

- Investigate chronic blood loss (menstruation, GI bleeding).

- Screen for malabsorption (celiac screen, H. pylori).

Lifestyle Tweaks

- Limit excessive alcohol, quit smoking, and manage inflammatory conditions.

By integrating these steps, most individuals can normalize TIBC, improve overall iron status, and reduce the risk of anemia or iron overload.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of abnormal Total Iron Binding Capacity (TIBC) levels?

The most frequent cause of an elevated TIBC is iron‑deficiency anemia, where the liver produces more transferrin to capture any available iron. Conversely, a low TIBC is most commonly seen in chronic inflammatory states, liver disease, or malnutrition, which suppress hepatic protein synthesis and reduce transferrin production.

How often should I get my Total Iron Binding Capacity (TIBC) tested?

For individuals undergoing iron supplementation, testing every 4–6 weeks is appropriate to track response. In the absence of treatment, a baseline check followed by annual screening (or sooner if symptoms develop) is sufficient. Patients with chronic conditions that affect iron metabolism may need more frequent monitoring as directed by their clinician.

Can lifestyle changes improve my Total Iron Binding Capacity (TIBC) levels?

Yes. Improving dietary iron intake, pairing iron‑rich foods with vitamin C, reducing intake of iron inhibitors, and addressing underlying inflammation or liver dysfunction can all help normalize TIBC. Regular physical activity, adequate sleep, and avoiding excessive alcohol also support optimal liver function and transferrin synthesis, thereby influencing TIBC.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Always consult a healthcare professional.