Calculating Transferrin Saturation: Formula and Guide

Calculating Transferrin Saturation: Formula and Guide

Introduction

Transferrin saturation (TSAT) is a pivotal laboratory index used to assess the balance between circulating iron and its primary transport protein, transferrin. Because iron is essential for hemoglobin synthesis, cellular respiration, and myriad enzymatic reactions, maintaining an appropriate TSAT is critical for preventing both iron‑deficiency anemia and iron‑overload disorders such as hereditary hemochromatosis. This article provides a step‑by‑step guide to calculating TSAT, explains the clinical meaning of the result, and offers evidence‑based recommendations on dietary sources, bioavailability, and supplementation to optimize transferrin saturation.

1. Understanding the Physiology

What Is Transferrin?

- Transferrin is a glycoprotein produced by the liver that binds two ferric (Fe³⁺) ions per molecule.

- It circulates in the plasma, delivering iron to cells via receptor‑mediated endocytosis.

- The total iron‑binding capacity (TIBC) reflects the maximum amount of iron that can be bound by all available transferrin sites.

Why TSAT Matters

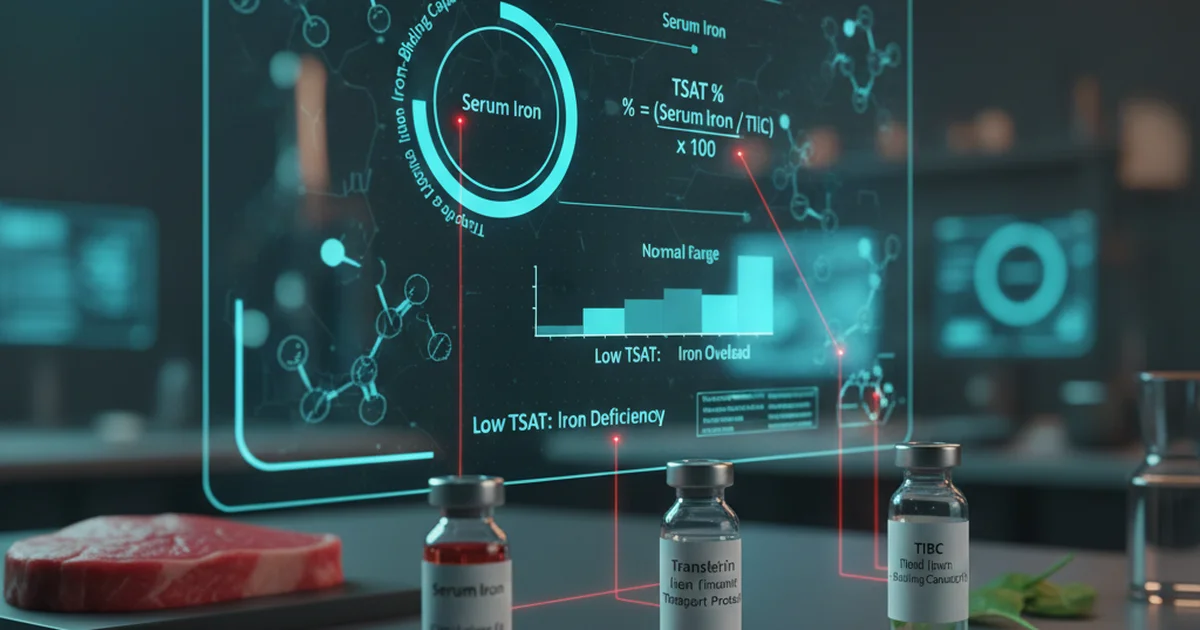

- TSAT = (Serum Iron ÷ TIBC) × 100%

- It indicates the proportion of transferrin that is actually saturated with iron at the time of sampling.

- Low TSAT (< 20 %) suggests insufficient iron for erythropoiesis, while high TSAT (> 45 %) raises concern for iron overload.

2. The Formula: How to Calculate Transferrin Saturation

| Step | Action | Example (Adult Male) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Obtain serum iron (µg/dL) | 110 µg/dL |

| 2 | Obtain TIBC (µg/dL) | 300 µg/dL |

| 3 | Divide serum iron by TIBC | 110 ÷ 300 = 0.367 |

| 4 | Multiply by 100 to express as a percent | 0.367 × 100 = 36.7 % |

Important: Ensure both values are reported in the same units (µg/dL or µmol/L). If the laboratory reports TIBC as “U” (units), convert using the appropriate factor supplied by the lab.

3. Reference Ranges

| Population | Normal Range | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Men | 20‑45 | % | Upper limit may be lower in iron‑deficiency screening |

| Adult Women (premenopausal) | 15‑35 | % | Hormonal fluctuations can affect iron status |

| Adult Women (postmenopausal) | 20‑45 | % | Similar to men after menopause |

| Children (1‑12 yr) | 15‑45 | % | Age‑dependent; infants have higher iron needs |

| Adolescents (13‑18 yr) | 20‑45 | % | Rapid growth increases iron demand |

| Elderly (> 65 yr) | 20‑45 | % | Chronic disease can skew values |

| Pregnancy (2nd trimester) | 15‑30 | % | Physiologic dilution reduces TSAT |

Values may vary slightly between laboratories; always interpret results in the context of the specific assay used.

4. Dietary Sources of Iron

Heme Iron (High Bioavailability)

| Food | Approx. Heme Iron (mg per 100 g) |

|---|---|

| Beef liver | 6.5 |

| Chicken liver | 5.0 |

| Red meat (beef, lamb) | 2.5‑3.0 |

| Pork | 2.0 |

| Fish (sardines, tuna) | 1.5‑2.0 |

- Bioavailability: 15‑35 % of heme iron is absorbed, largely unaffected by dietary inhibitors.

Non‑Heme Iron (Variable Bioavailability)

| Food | Approx. Non‑Heme Iron (mg per 100 g) |

|---|---|

| Lentils (cooked) | 3.3 |

| Spinach (cooked) | 3.6 |

| Chickpeas (cooked) | 2.9 |

| fortified breakfast cereal | 4‑18 (depends on brand) |

| Tofu (firm) | 2.7 |

- Bioavailability: 2‑20 %, strongly influenced by enhancers (vitamin C, heme iron) and inhibitors (phytates, polyphenols, calcium).

Practical Tips for Boosting Iron Intake

- Pair non‑heme iron foods with a source of vitamin C (citrus juice, bell peppers, strawberries) to increase absorption by up to threefold.

- Cook leafy greens (e.g., spinach) in a small amount of water and discard excess liquid to reduce oxalate content, a known inhibitor.

- Avoid consuming large amounts of tea, coffee, or high‑calcium dairy within 1‑2 hours of iron‑rich meals.

5. Bioavailability: What Affects How Much Iron Gets Into the Blood?

| Factor | Effect on Absorption | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Heme vs. non‑heme | Heme >> non‑heme | Direct transporter for heme iron |

| Vitamin C | ↑ absorption | Reduces Fe³⁺ to Fe²⁺, forming soluble complexes |

| Phytates (grains, legumes) | ↓ absorption | Chelate iron, forming insoluble complexes |

| Polyphenols (tea, coffee, red wine) | ↓ absorption | Bind iron, preventing uptake |

| Calcium | ↓ absorption (moderate) | Competes with iron for shared transport pathways |

| Gastric acidity | ↑ absorption | Solubilizes ferric iron; hypochlorhydria reduces uptake |

| Inflammation | ↓ serum iron, ↑ ferritin | Hepcidin up‑regulation traps iron in macrophages, lowering TSAT |

Clinical pearl: In patients with chronic inflammatory conditions, TSAT may be low despite normal or elevated body iron stores because hepcidin-driven sequestration reduces circulating iron.

6. Supplementation Strategies

When to Consider Iron Supplements

- Documented TSAT < 20 % with symptoms of iron‑deficiency (fatigue, pallor, restless legs).

- Pregnancy (especially second trimester) when dietary intake cannot meet increased demand.

- Chronic blood loss (e.g., heavy menstrual bleeding, gastrointestinal bleeding).

Choosing the Right Form

| Form | Elemental Iron per Tablet | Typical Dose for Deficiency | Absorption Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ferrous sulfate | 20 % | 325 mg (≈65 mg elemental) daily | 10‑15 % |

| Ferrous gluconate | 12 % | 240 mg (≈28 mg elemental) daily | 10‑12 % |

| Ferrous fumarate | 33 % | 200 mg (≈66 mg elemental) daily | 12‑15 % |

| Iron polymaltose complex (IPC) | 30 % | 100 mg (≈30 mg elemental) daily | 10‑13 % |

| Heme iron polypeptide | 12 % | 100 mg (≈12 mg elemental) daily | 20‑30 % (less affected by inhibitors) |

Key points:

- Ferrous salts are inexpensive and effective but cause gastrointestinal upset in up to 30 % of users.

- Heme iron supplements have higher bioavailability and fewer side effects but are costlier.

- Liquid iron preparations (e.g., iron drops) are useful for children and patients with dysphagia.

Dosing Recommendations

- Start with once‑daily dosing on an empty stomach (30 minutes before breakfast) to maximize absorption.

- If gastrointestinal intolerance occurs, take with a small amount of food and a source of vitamin C (e.g., orange juice).

- Avoid concurrent calcium supplements or antacids within 2 hours of iron dosing.

Monitoring

- Re‑check TSAT and ferritin after 4‑6 weeks of therapy.

- Adjust dose to keep TSAT between 20‑45 % and ferritin > 30 µg/L (or > 50 µg/L in men).

- Discontinue or reduce supplementation when TSAT normalizes to prevent iron overload.

7. Clinical Interpretation of TSAT Results

| TSAT Range | Interpretation | Typical Causes |

|---|---|---|

| < 15 % | Severe iron deficiency | Chronic blood loss, malabsorption, pregnancy |

| 15‑20 % | Mild‑to‑moderate deficiency | Suboptimal dietary intake, early-stage disease |

| 20‑45 % | Normal | Adequate iron balance |

| 45‑55 % | Upper‑normal / borderline overload | Early hemochromatosis, excess supplementation |

| > 55 % | Iron overload | Hereditary hemochromatosis, repeated transfusions, sideroblastic anemia |

Note: TSAT must be interpreted alongside serum ferritin, hemoglobin, and clinical context. Ferritin reflects stored iron but is an acute‑phase reactant; in inflammation, ferritin may be elevated while TSAT remains low.

8. Actionable Advice for Optimizing Transferrin Saturation

- Assess Baseline: Obtain serum iron, TIBC, and calculate TSAT at least once a year for at‑risk individuals (e.g., menstruating women, vegetarians, chronic disease patients).

- Dietary Optimization:

- Include heme iron sources (lean red meat, poultry liver) 2‑3 times per week.

- Pair non‑heme iron meals with vitamin C‑rich foods.

- Limit tea/coffee during meals; schedule them between meals.

- Address Inhibitors:

- Soak, sprout, or ferment legumes and grains to reduce phytate content.

- Use cooking methods that preserve vitamin C (e.g., quick stir‑fry).

- Supplement Wisely:

- Choose the least irritating formulation that meets the required elemental iron dose.

- Monitor for side effects (nausea, constipation) and adjust timing or formulation accordingly.

- Treat Underlying Conditions:

- Manage chronic inflammation, celiac disease, or gastric hypochlorhydria, as these can blunt absorption despite adequate intake.

- Re‑evaluate: Repeat TSAT and ferritin after 4‑6 weeks of any dietary or supplement change. Adjust the plan based on the new values.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of abnormal Transferrin Saturation levels?

The most frequent cause of a low TSAT is iron‑deficiency anemia, usually stemming from inadequate dietary intake, chronic blood loss (e.g., heavy menstrual periods or gastrointestinal bleeding), or malabsorption disorders such as celiac disease. Conversely, a high TSAT most commonly results from hereditary hemochromatosis or excessive iron supplementation, where the body’s regulatory mechanisms are overwhelmed and excess iron circulates bound to transferrin.

How often should I get my Transferrin Saturation tested?

For individuals with normal iron status and no risk factors, testing every 1–2 years is sufficient. People at higher risk—such as menstruating women, vegetarians, patients with chronic inflammatory diseases, or those on long‑term iron supplements—should have TSAT assessed every 6–12 months or sooner if symptoms of iron imbalance appear. After initiating or changing iron therapy, re‑testing at 4–6 weeks helps gauge response and avoid overload.

Can lifestyle changes improve my Transferrin Saturation levels?

Absolutely. Dietary modifications that increase heme iron intake, combine non‑heme iron foods with vitamin C, and limit inhibitors (tea, coffee, calcium) can raise a low TSAT. Addressing gastrointestinal health (e.g., treating H. pylori infection, managing reflux) improves absorption. Additionally, reducing alcohol consumption and maintaining a healthy weight lower inflammation, which can enhance iron mobilization and normalize TSAT.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Always consult a healthcare professional.