High Transferrin Saturation: Hemochromatosis Risks

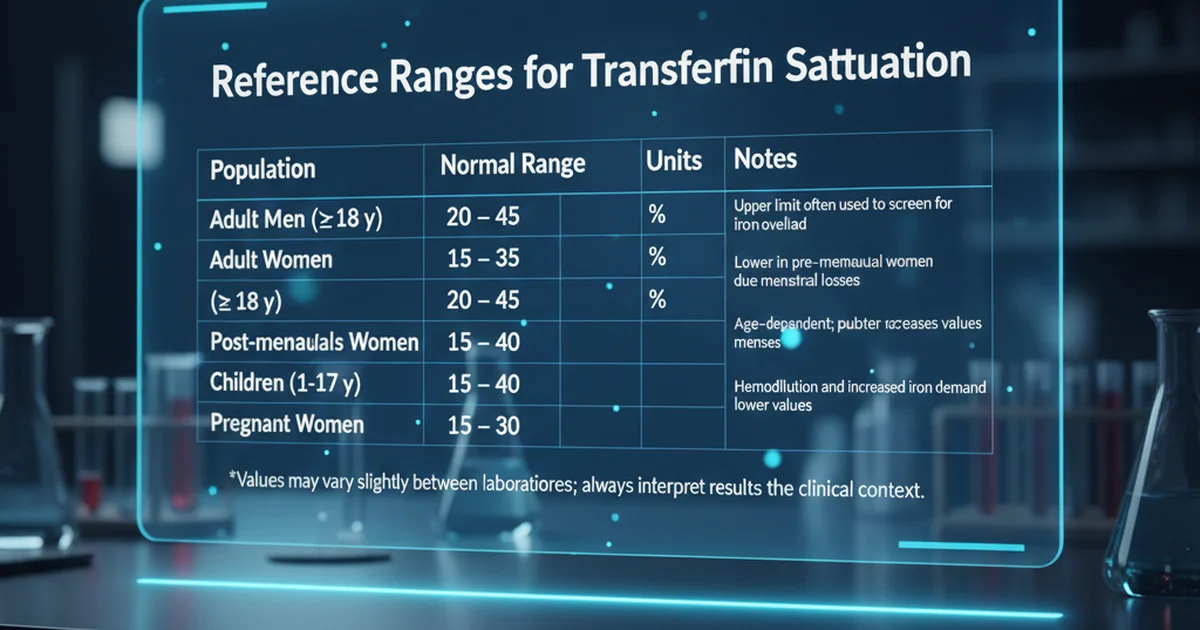

Reference Ranges for Transferrin Saturation

| Population | Normal Range | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Men (≥ 18 y) | 20 – 45 | % | Upper limit often used to screen for iron overload |

| Adult Women (≥ 18 y) | 15 – 35 | % | Lower in pre‑menopausal women due to menstrual losses |

| Post‑menopausal Women | 20 – 45 | % | Similar to men after cessation of menses |

| Children (1‑17 y) | 15 – 40 | % | Age‑dependent; puberty increases values in boys |

| Pregnant Women | 15 – 30 | % | Hemodilution and increased iron demand lower values |

Values may vary slightly between laboratories; always interpret results in the clinical context.

Understanding Transferrin Saturation

What Is Transferrin Saturation?

Transferrin is the primary iron‑binding protein in plasma; it transports iron to tissues.

Transferrin saturation (TS) is the percentage of transferrin binding sites that are occupied by iron.

It is calculated as:

[ \text{TS (%)} = \frac{\text{Serum Iron}}{\text{Total Iron‑Binding Capacity}} \times 100 ]

TS reflects the balance between iron intake, storage, and utilization.

Why TS Matters Clinically

- Low TS (< 15 %) suggests iron deficiency or chronic blood loss.

- High TS (> 45 % in men, > 35 % in women) raises suspicion for iron overload, the most common cause being hereditary hemochromatosis (HH).

- Persistent elevation can lead to organ damage (liver cirrhosis, cardiomyopathy, endocrine dysfunction, arthropathy).

Causes of Elevated Transferrin Saturation

| Category | Typical Mechanism | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic iron overload | Mutations in HFE, HJV, HAMP, TFR2, SLC40A1 | Autosomal‑dominant or recessive; often asymptomatic until adulthood |

| Acquired iron overload | Chronic transfusion therapy, excessive oral iron supplementation, sideroblastic anemia | Seen in thalassemia, myelodysplastic syndromes |

| Dietary excess | Very high intake of heme iron (red meat, organ meats) | Rarely causes TS > 50 % alone; usually synergizes with genetic predisposition |

| Liver disease | Impaired hepcidin synthesis, increased iron release from damaged hepatocytes | Alcoholic liver disease, non‑alcoholic steatohepatitis |

| Metabolic disorders | Insulin resistance, obesity → altered hepcidin regulation | Contribute to modest TS elevation |

Hemochromatosis: The Primary Concern

Pathophysiology

- HFE‑related HH (C282Y homozygosity) accounts for > 90 % of cases in individuals of Northern European descent.

- The mutated HFE protein fails to interact properly with transferrin receptor, leading to inadequate hepcidin signaling.

- Low hepcidin removes the “brake” on intestinal iron absorption, causing continuous uptake of dietary iron.

Clinical Spectrum

| Stage | Typical Findings |

|---|---|

| Pre‑clinical | Elevated TS, normal ferritin, no symptoms |

| Biochemical iron overload | Elevated ferritin, mild hepatic enzyme elevation |

| Organ involvement | Cirrhosis, cardiomyopathy, diabetes mellitus, skin hyperpigmentation, arthropathy (especially MCP joints) |

| Advanced disease | Hepatocellular carcinoma, heart failure, endocrine failure |

When to Suspect HH

- Male > 30 y or female > 50 y with TS > 45 % (men) / > 35 % (women) on two separate occasions.

- Family history of HH, liver disease, early-onset diabetes, or joint problems.

- Unexplained elevated ferritin (> 300 µg/L in men, > 200 µg/L in women) together with high TS.

Dietary Sources of Iron and Their Impact on TS

Heme Iron (Highly Bioavailable)

| Food | Approx. Heme Iron (mg/100 g) |

|---|---|

| Beef liver | 6.5 |

| Beef steak | 2.6 |

| Lamb | 2.3 |

| Chicken thigh (dark meat) | 1.3 |

| Turkey (dark meat) | 1.2 |

- Absorption rate: 15‑35 % of ingested heme iron is absorbed, largely independent of other dietary factors.

- Clinical implication: Individuals with HH should limit organ meats and large portions of red meat, especially cooked in iron‑rich cast‑iron cookware.

Non‑Heme Iron (Variable Bioavailability)

| Food | Approx. Non‑Heme Iron (mg/100 g) |

|---|---|

| Lentils (cooked) | 3.3 |

| Spinach (cooked) | 3.6 |

| Tofu (firm) | 2.7 |

| Fortified breakfast cereal | 18 (varies) |

| Oats (dry) | 4.3 |

- Absorption rate: 2‑20 % depending on enhancers (vitamin C, meat factor) and inhibitors (phytates, polyphenols, calcium).

- Clinical implication: Even high non‑heme iron foods rarely push TS into the pathological range unless combined with genetic susceptibility.

Iron‑Enhancing Factors

- Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) converts ferric (Fe³⁺) to ferrous (Fe²⁺) form, boosting absorption by up to 2‑fold.

- Meat factor (unknown peptide(s) in animal protein) improves non‑heme iron uptake.

Iron‑Inhibiting Factors

- Phytates (found in whole grains, legumes, nuts) bind iron and reduce absorption.

- Polyphenols (tea, coffee, red wine) form insoluble complexes.

- Calcium (dairy, supplements) competitively inhibits iron transporters.

Practical Dietary Strategies to Modulate Transferrin Saturation

Assess Current Iron Intake

- Keep a 3‑day food diary.

- Calculate total heme iron (aim for ≤ 5 mg/day if TS is high).

Prioritize Iron‑Blocking Foods

- Include tea or coffee with meals (avoid excessive caffeine if you have other health concerns).

- Use whole grains and legume‑based dishes that contain phytates; soaking or sprouting reduces phytate content if you need more iron.

Control Vitamin C Timing

- Separate vitamin C‑rich foods (citrus, strawberries) from iron‑rich meals by at least 1 hour to limit the absorption boost.

Limit Iron‑Fortified Products

- Many breakfast cereals and nutrition bars are fortified with elemental iron (often as ferrous sulfate, highly absorbable). Choose unfortified alternatives if TS is persistently > 45 %.

Avoid Cast‑Iron Cookware for Acidic Dishes

- Cooking tomatoes or other acidic foods in cast‑iron pans can leach up to 5 mg of iron per serving. Switch to stainless steel or enamel when possible.

Supplementation: When It Helps and When It Harms

Iron Supplements – Indications

- Deficiency anemia (TS < 15 % with low ferritin).

- Pregnancy (increased iron demands).

Forms of Iron Supplements

| Form | Typical Elemental Iron (mg) per tablet | Absorption |

|---|---|---|

| Ferrous sulfate | 20 | High |

| Ferrous gluconate | 12 | Moderate |

| Ferrous fumarate | 33 | High |

| Polysaccharide‑iron complex | 50 | Variable, often slower release |

Risks in High TS Individuals

- Excessive dosing can push TS into the dangerous range within days.

- Oral iron can cause gastrointestinal irritation, leading to poor adherence and unnecessary iron loss (blood in stool).

Evidence‑Based Guidance

- Do NOT supplement iron if TS is > 45 % (men) or > 35 % (women) unless a documented deficiency exists and a specialist recommends a carefully monitored trial.

- In patients with HH undergoing phlebotomy, iron supplements are contraindicated because they counteract therapeutic depletion.

Alternative Supplements for Iron‑Related Symptoms

- Vitamin C (500 mg) can be used after iron‑depleting therapy to improve hemoglobin synthesis without increasing iron absorption when taken between meals.

- Zinc and copper supplementation may be needed after repeated phlebotomy, as iron loss can affect their metabolism.

Management of Elevated Transferrin Saturation

1. Confirm the Finding

- Repeat TS and ferritin in 6‑8 weeks to rule out transient spikes (e.g., after a high‑iron meal).

2. Genetic Testing

- If TS remains > 45 % (men) / > 35 % (women) and ferritin is elevated, order HFE genotyping (C282Y and H63D).

3. Therapeutic Phlebotomy

- Standard first‑line therapy for HH.

- Initial phase: Remove 500 mL of blood weekly until ferritin < 50 µg/L and TS < 25 %.

- Maintenance phase: Phlebotomy every 2‑4 months to keep ferritin in the 50‑100 µg/L range.

4. Lifestyle and Dietary Modifications

- Follow the dietary strategies outlined above.

- Alcohol reduction is crucial; alcohol increases intestinal iron absorption and accelerates liver injury.

5. Monitoring

| Parameter | Frequency | Target |

|---|---|---|

| Transferrin Saturation | Every 6‑12 months after stabilization | < 30 % |

| Ferritin | Every 3‑6 months during phlebotomy | 50‑100 µg/L |

| Liver function tests | Annually (more often if liver disease) | Within normal limits |

| Cardiac MRI (if indicated) | Every 2‑3 years in established disease | No iron overload |

Actionable Take‑Home Advice

- Know your numbers: If you are a male over 30 or a post‑menopausal female, aim for TS ≤ 45 % (men) / ≤ 35 % (women).

- Track iron‑rich meals: Limit heme iron to ≤ 5 mg/day when TS is high.

- Separate vitamin C: Consume citrus fruits at least an hour apart from iron‑dense foods.

- Drink tea/coffee with meals: This simple habit can cut iron absorption by up to 50 %.

- Avoid iron‑fortified foods unless a deficiency is proven.

- Schedule regular labs: Annual TS and ferritin testing is advisable for anyone with a family history of HH.

- Seek specialist care if TS remains elevated after dietary changes; early phlebotomy prevents irreversible organ damage.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of abnormal Transferrin Saturation levels?

The leading cause of a high transferrin saturation is hereditary hemochromatosis, especially the HFE‑related C282Y homozygous mutation. In the absence of genetic predisposition, chronic transfusion therapy, excessive oral iron supplementation, or severe liver disease can also raise TS, but these are far less common.

How often should I get my Transferrin Saturation tested?

- Average‑risk adults: Every 3‑5 years as part of routine health screening.

- Individuals with a family history of hemochromatosis, unexplained elevated ferritin, or metabolic liver disease: Annually.

- Patients undergoing phlebotomy or iron‑depletion therapy: Every 6‑12 months until targets are reached, then every 1‑2 years for maintenance.

Can lifestyle changes improve my Transferrin Saturation levels?

Yes. Dietary modifications (reducing heme iron, separating vitamin C, using iron‑inhibiting beverages) can lower TS by 5‑15 % in many people. Limiting alcohol, maintaining a healthy body weight, and avoiding iron‑fortified products further support normal iron metabolism. In genetically predisposed individuals, lifestyle changes alone rarely normalize TS, but they enhance the effectiveness of therapeutic phlebotomy and reduce the risk of organ damage.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Always consult a healthcare professional.