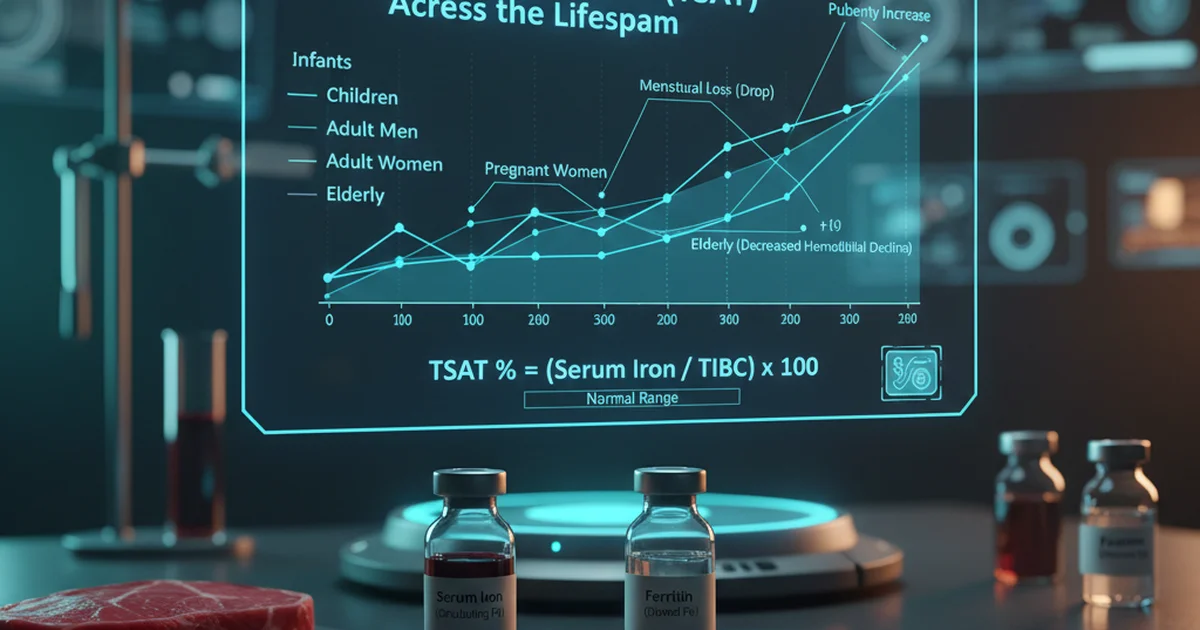

Normal Transferrin Saturation Percentages by Age

Transferrin saturation (TSAT) reflects the proportion of circulating transferrin that is bound to iron. It is expressed as a percentage and is a key indicator of iron availability for erythropoiesis and cellular metabolism. Understanding how TSAT varies across the lifespan helps clinicians and individuals interpret laboratory results, guide dietary choices, and decide when supplementation may be warranted.

Reference Ranges Table

| Population | Normal TSAT Range | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newborn (0‑28 days) | 20‑50 | % | Rapid post‑natal rise as iron stores are mobilized |

| Infants (1‑12 months) | 15‑35 | % | Breast‑fed infants often lower; formula‑fed higher |

| Early Childhood (1‑5 years) | 20‑40 | % | Reflects growth‑related iron demand |

| School‑age Children (6‑12 years) | 25‑45 | % | Slight increase as dietary iron intake rises |

| Adolescents (13‑18 years) | 30‑50 | % | Pubertal growth spurt raises iron requirement |

| Adult Men (19‑64 years) | 20‑50 | % | Stable range; higher end may suggest overload |

| Adult Women (19‑49 years) | 15‑40 | % | Lower due to menstrual losses |

| Post‑menopausal Women (≥50 years) | 20‑45 | % | Converges toward male values |

| Elderly (≥65 years) | 15‑45 | % | May decline with malabsorption or chronic disease |

Values are typical laboratory reference intervals; individual labs may have slight variations.

Understanding Transferrin Saturation

What TSAT Measures

- Transferrin is the primary iron‑transport protein in plasma.

- TSAT = (Serum Iron ÷ Total Iron‑Binding Capacity) × 100.

- It indicates how much of the transport capacity is occupied, providing a snapshot of iron availability for tissue use.

Why TSAT Matters

- Low TSAT (< 15 %) suggests iron‑deficient erythropoiesis, chronic blood loss, or malabsorption.

- High TSAT (> 50 %) may signal iron overload conditions (e.g., hereditary hemochromatosis) or excessive supplementation.

- TSAT is more sensitive than serum ferritin for detecting early iron deficiency in the presence of inflammation, because ferritin is an acute‑phase reactant.

Dietary Sources of Iron Influencing TSAT

Iron exists in two dietary forms, each with distinct bioavailability:

| Iron Form | Typical Sources | Approx. Absorption (when taken alone) |

|---|---|---|

| Heme iron | Red meat, poultry, fish, organ meats | 15‑35 % |

| Non‑heme iron | Legumes, fortified cereals, spinach, nuts, seeds | 2‑20 % (strongly affected by enhancers/inhibitors) |

Enhancers of Non‑heme Iron Absorption

- Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) – reduces ferric to ferrous iron, increasing uptake.

- Animal protein (the “meat factor”) – peptides from meat improve non‑heme iron absorption.

- Organic acids (citric, malic) – present in fruits and certain vegetables.

Inhibitors of Non‑heme Iron Absorption

- Phytates – found in whole grains, legumes, nuts; bind iron.

- Polyphenols – abundant in tea, coffee, cocoa; form insoluble complexes.

- Calcium – high dairy intake can temporarily reduce iron absorption.

- Soy proteins – contain iron‑binding peptides.

Practical Dietary Strategies

- Pair iron‑rich plant foods with vitamin C‑rich items (e.g., lentil soup with bell‑pepper garnish).

- Consume heme sources a few times per week for individuals at risk of deficiency (adolescents, premenopausal women).

- Avoid drinking tea or coffee with meals; wait at least an hour after eating.

- Soak, sprout, or ferment grains and legumes to reduce phytate content and improve bioavailability.

Bioavailability Across the Lifespan

| Age Group | Dominant Iron Source | Typical Bioavailability | Impact on TSAT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infants (breast‑fed) | Lactoferrin‑bound iron in breast milk | ~50 % (highly bioavailable) | Maintains TSAT within neonatal range |

| Infants (formula‑fed) | Fortified iron (non‑heme) | 10‑15 % | Slightly higher TSAT than breast‑fed |

| Children | Mixed diet (meat + fortified cereals) | 10‑25 % overall | Gradual rise to school‑age range |

| Adolescents | Increased meat consumption, menstrual losses (girls) | 15‑30 % | TSAT peaks; girls may dip during heavy cycles |

| Adults | Varied diet; supplementation common | 10‑35 % | Stable adult range; excess supplementation may push TSAT > 50 % |

| Elderly | Often reduced meat intake, higher phytate consumption | 5‑15 % (lower) | TSAT may fall, especially with chronic disease |

Supplementation: When and How

Indications for Iron Supplementation

- Documented TSAT < 15 % with accompanying low ferritin and hemoglobin.

- Pregnancy (first trimester TSAT < 20 %).

- Chronic blood loss (e.g., heavy menstrual bleeding, gastrointestinal bleeding).

- Malabsorption syndromes (celiac disease, bariatric surgery).

Choosing the Right Form

| Form | Elemental Iron Content (per tablet) | Absorption Rate | Common Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ferrous sulfate | 65 mg | Highest (≈20 %) | GI irritation, constipation |

| Ferrous gluconate | 35 mg | Moderate | Less GI upset |

| Ferrous fumarate | 106 mg | High | Similar to sulfate |

| Heme iron polypeptide | 12 mg | 30‑40 % (no dietary inhibitors) | Minimal GI issues |

| Iron bisglycinate (chelated) | 27 mg | 20‑30 % (food‑independent) | Well‑tolerated |

Dosage Guidelines

- Mild deficiency: 60‑100 mg elemental iron daily, divided into two doses.

- Moderate‑severe deficiency: 120‑200 mg elemental iron daily, divided.

- Pregnant women: 30‑60 mg elemental iron daily (often 27 mg from ferrous gluconate).

Important: Do not exceed 200 mg elemental iron per day without specialist supervision, as excess can raise TSAT > 50 % and cause oxidative stress.

Optimizing Absorption

- Take iron on an empty stomach (30 min before meals) for maximal absorption.

- If GI intolerance occurs, co‑administer with a small amount of food and a vitamin C source (e.g., orange juice).

- Avoid calcium supplements, antacids, or high‑phytate foods within 2 hours of the iron dose.

Monitoring Therapy

- Re‑check TSAT and ferritin after 4‑6 weeks of therapy.

- Expect TSAT to rise into the mid‑30 % range if treatment is effective.

- Once TSAT stabilizes, transition to a maintenance dose (30‑45 mg elemental iron) for another 3‑6 months to replenish stores.

Clinical Interpretation of TSAT by Age

Infants & Toddlers

- TSAT < 15 % may indicate inadequate iron in formula or early weaning from breast milk.

- Encourage iron‑fortified cereals and pureed meats; monitor growth parameters.

School‑Age Children

- Low TSAT often reflects high growth velocity or dietary insufficiency (vegetarian diets).

- School lunch programs should include heme iron options or fortified grains with vitamin C.

Adolescents

- Girls: TSAT 15‑40 %; monitor during menstrual cycles.

- Boys: TSAT 30‑50 %; high TSAT (> 55 %) may warrant evaluation for hereditary hemochromatosis, especially if family history exists.

Adults

- Men: TSAT 20‑50 %; values > 55 % should prompt iron studies, liver function tests, and genetic screening.

- Women (premenopausal): TSAT 15‑40 %; heavy menstrual bleeding may push TSAT below 15 %.

Elderly

- TSAT may drift toward the lower end (15‑30 %) due to reduced gastric acid, polypharmacy, and co‑existing chronic disease.

- Assess for anemia of chronic disease versus true iron deficiency; ferritin may be elevated despite low TSAT.

Actionable Advice for Maintaining Optimal TSAT

- Eat a balanced diet that includes at least two heme‑iron servings per week (e.g., lean beef, chicken, fish).

- Pair plant‑based iron foods with vitamin C‑rich fruits or vegetables (e.g., spinach salad with strawberries).

- Limit inhibitors: avoid tea/coffee with meals and space calcium supplements away from iron doses.

- Screen at risk: women with heavy menstrual bleeding, athletes, vegetarians, and the elderly should have TSAT checked annually.

- Use supplements wisely: start with the lowest effective dose, monitor TSAT, and taper to maintenance once repletion is achieved.

- Stay hydrated and manage GI health: constipation can reduce iron absorption; adequate fluid intake and fiber help.

- Consider underlying conditions: chronic kidney disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and celiac disease can impair iron uptake; treat the primary disease alongside iron therapy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of abnormal Transferrin Saturation levels?

The leading cause of low TSAT is iron deficiency, most often due to chronic blood loss (menstrual bleeding, gastrointestinal bleeding) or inadequate dietary intake. High TSAT is most frequently seen in hereditary hemochromatosis, excessive iron supplementation, or repeated blood transfusions.

How often should I get my Transferrin Saturation tested?

For individuals without risk factors, checking TSAT every 2‑3 years as part of a routine metabolic panel is sufficient. Those with risk factors (e.g., heavy menstrual periods, pregnancy, known anemia, chronic disease, or a family history of iron overload) should have TSAT assessed annually or every 6 months if undergoing iron therapy.

Can lifestyle changes improve my Transferrin Saturation levels?

Absolutely. Adjusting dietary patterns—increasing heme iron intake, pairing non‑heme iron foods with vitamin C, and reducing intake of absorption inhibitors—can raise low TSAT. Conversely, avoiding excessive iron‑rich supplements and limiting alcohol (which can increase iron absorption) helps keep high TSAT within a safe range. Regular physical activity promotes healthy red blood cell turnover, and maintaining a healthy weight reduces chronic inflammation that can skew iron markers.

By understanding the age‑specific reference ranges, the influence of diet and supplements, and the practical steps to optimize iron status, individuals can keep their transferrin saturation within healthy limits and support overall hematologic health.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Always consult a healthcare professional.