Transferrin Saturation Explained: The Complete Guide

Reference Ranges

| Population | Normal Range | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Men (18‑65 yr) | 20‑45 | % | Slightly higher in smokers |

| Adult Women (18‑65 yr) | 15‑35 | % | Lower in pre‑menopausal women |

| Pregnant Women (any trimester) | 15‑30 | % | Physiologic dilution |

| Children (1‑12 yr) | 20‑40 | % | Age‑dependent; infants have higher values |

| Elderly (≥ 65 yr) | 15‑40 | % | Decline in hepatic synthesis may lower values |

| Patients with hereditary hemochromatosis | > 45 | % | Diagnostic threshold for iron overload |

Values are intended as general guidance; individual laboratories may use slightly different cut‑offs.

Introduction

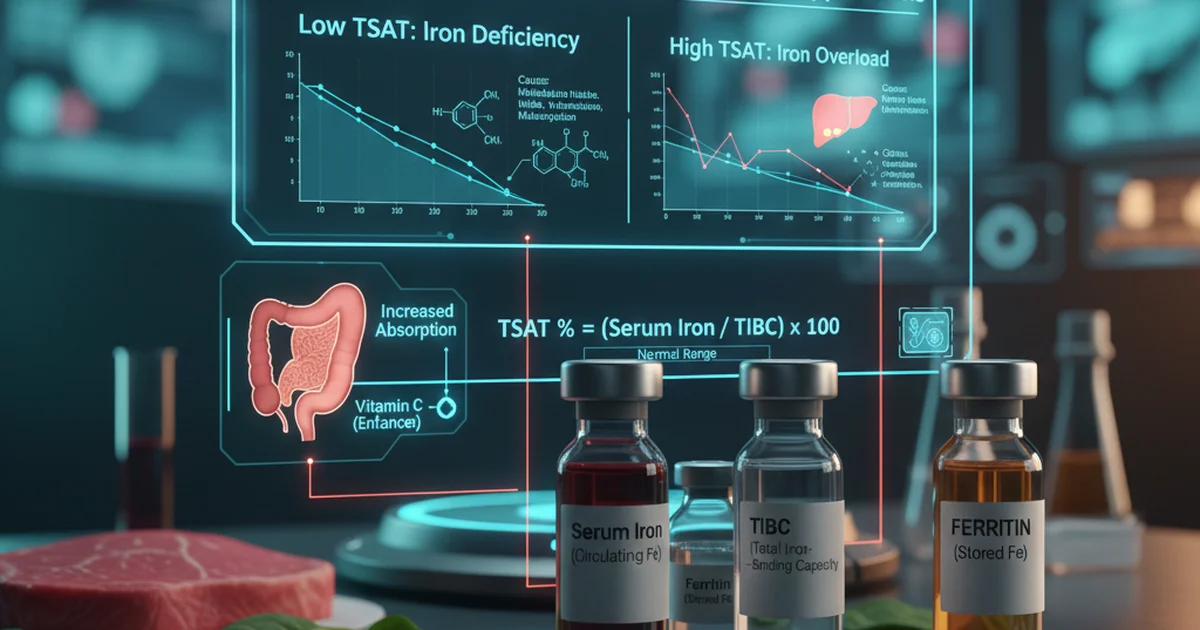

Transferrin saturation (TSAT) is a calculated laboratory value that reflects the proportion of the iron‑binding sites on the plasma protein transferrin that are occupied by iron. It is a cornerstone metric in the evaluation of iron status, bridging the gap between serum iron (the amount of circulating iron at a single point in time) and total iron‑binding capacity (TIBC, the maximum amount of iron that transferrin could bind). Understanding TSAT helps clinicians differentiate iron deficiency, iron overload, and anemia of chronic disease, and it guides dietary and supplemental strategies to correct imbalances.

Physiology of Transferrin and Saturation

What Is Transferrin?

- Primary iron‑transport protein in blood, synthesized by the liver.

- Each transferrin molecule can bind two ferric (Fe³⁺) ions.

- The concentration of transferrin adjusts to meet the body’s iron demand, rising in iron deficiency and falling in iron overload.

How TSAT Is Calculated

[ \text{TSAT (%)} = \frac{\text{Serum Iron (µg/dL)}}{\text{TIBC (µg/dL)}} \times 100 ]

- Serum iron reflects the instantaneous pool of iron bound to transferrin.

- TIBC approximates the total number of binding sites available (i.e., the total transferrin concentration).

Because both components fluctuate with meals, inflammation, and diurnal rhythms, clinicians usually obtain a fasting sample and repeat testing if results are borderline.

Clinical Significance

| TSAT Level | Interpretation | Typical Clinical Context |

|---|---|---|

| < 15 % | Low → Iron‑deficiency or chronic blood loss | Menstruating women, gastrointestinal bleeding, malnutrition |

| 15‑45 % | Normal → Adequate iron availability | Healthy adults, well‑balanced diets |

| > 45 % | High → Iron overload risk | Hereditary hemochromatosis, repeated transfusions, excessive supplementation |

Critical point: A normal TSAT does not rule out functional iron deficiency in the setting of inflammation; ferritin, soluble transferrin receptor, and C‑reactive protein must be interpreted together.

Dietary Sources of Iron and Their Impact on TSAT

Iron exists in two dietary forms, each with distinct bioavailability:

1. Heme Iron (Highly Bioavailable)

- Sources: Red meat, poultry, fish, organ meats (liver, kidney).

- Absorption rate: Approximately 15‑35 % of ingested heme iron is absorbed, largely unaffected by other dietary components.

2. Non‑Heme Iron (Variable Bioavailability)

- Sources: Legumes (lentils, beans, chickpeas), fortified cereals, tofu, nuts, seeds, dark leafy greens (spinach, kale), whole grains, dried fruits (apricots, raisins).

- Absorption rate: Typically 2‑20 %, heavily influenced by enhancers and inhibitors.

Enhancers of Non‑Heme Iron Absorption

| Enhancer | Mechanism | Practical Tips |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) | Reduces Fe³⁺ to Fe²⁺, forming soluble complexes | Add citrus juice, strawberries, bell peppers to meals |

| Meat, fish, poultry factor | Unknown peptide(s) that promote uptake | Include a small portion of animal protein with plant‑based iron foods |

| Citric acid | Chelates iron, keeping it soluble | Use lemon or lime juice as a dressing |

Inhibitors of Non‑Heme Iron Absorption

| Inhibitor | Mechanism | Practical Tips |

|---|---|---|

| Phytates (found in whole grains, legumes, nuts) | Bind iron strongly, forming insoluble complexes | Soak, ferment, or sprout grains and legumes to reduce phytate content |

| Polyphenols (tea, coffee, red wine) | Form stable iron complexes | Consume beverages between meals rather than with iron‑rich foods |

| Calcium (dairy, supplements) | Competes for transport pathways | Separate calcium‑rich foods/supplements by at least 2 hours from iron‑rich meals |

| Oxalates (spinach, rhubarb, beet greens) | Form insoluble iron oxalate | Pair oxalate‑rich greens with vitamin C sources to mitigate inhibition |

Bioavailability: From Plate to Plasma

- Stomach (pH ≈ 2): Acidic environment releases iron from food matrices. Proton pumps and gastric acid are critical; individuals on chronic proton‑pump inhibitors may experience reduced iron absorption.

- Duodenum: Primary site of iron uptake via the divalent metal transporter‑1 (DMT‑1) for non‑heme iron and heme carrier protein‑1 (HCP‑1) for heme iron.

- Enterocyte Regulation: Iron‑responsive element (IRE)/iron‑regulatory protein (IRP) system modulates ferroportin (exporter) expression based on cellular iron stores.

- Systemic Control: Hepcidin, a liver‑derived peptide, binds ferroportin and triggers its internalization, effectively blocking iron egress from enterocytes and macrophages. Elevated hepcidin (in inflammation or iron overload) lowers TSAT despite adequate dietary intake.

Key takeaway: Even with a diet rich in iron, high hepcidin can keep TSAT low; conversely, low hepcidin can raise TSAT rapidly with modest iron intake.

Supplementation Strategies to Optimize TSAT

When to Supplement

- Documented TSAT < 15 % with symptoms of iron deficiency (fatigue, pica, restless legs).

- Chronic blood loss (e.g., heavy menstrual bleeding, gastrointestinal ulcer).

- Pregnancy (especially in the second and third trimesters).

Choosing the Right Form

| Form | Elemental Iron Content | Typical Dose (per day) | Absorption Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ferrous sulfate | 20 % | 325 mg (≈ 65 mg elemental) | Gold standard, best studied |

| Ferrous gluconate | 12 % | 300 mg (≈ 36 mg elemental) | Gentler on GI tract |

| Ferrous fumarate | 33 % | 200 mg (≈ 66 mg elemental) | High elemental iron, moderate tolerance |

| Iron polymaltose complex | 10‑12 % | 100 mg (≈ 10‑12 mg elemental) | Slow release, minimal constipation |

| Heme iron polypeptide | 20‑25 % | 100 mg (≈ 20‑25 mg elemental) | Highest bioavailability, less affected by diet |

Clinical tip: Start with a low dose (e.g., 30 mg elemental iron) if the patient has a history of gastrointestinal upset, then titrate upward based on tolerance and repeat TSAT in 4‑6 weeks.

Timing and Co‑Factors

- Take on an empty stomach (30 minutes before meals) to maximize absorption.

- Co‑administer with vitamin C (e.g., a glass of orange juice) to enhance uptake.

- Avoid calcium, antacids, tea, coffee, and high‑phytate foods within 2 hours of the dose.

Monitoring and Safety

- Re‑measure TSAT and ferritin 4–6 weeks after initiating therapy; adjust dose accordingly.

- Upper safety limit: 45 mg elemental iron per day for most adults without deficiency; higher doses increase risk of oxidative stress, gut dysbiosis, and iron‑induced organ damage.

- Watch for adverse effects: nausea, constipation, dark stools, and, rarely, iron‑induced gastritis.

When to Stop

- TSAT ≥ 30 % and ferritin ≥ 100 µg/L in women or ≥ 150 µg/L in men generally indicate repletion.

- Discontinue supplementation or switch to a maintenance dose (e.g., 10‑15 mg elemental iron daily) to avoid oversaturation.

Dietary Strategies to Raise Low TSAT

- Prioritize heme iron sources at least twice weekly (e.g., lean beef, chicken liver).

- Combine non‑heme iron foods with vitamin C‑rich items (e.g., lentil soup with a squeeze of lemon).

- Reduce inhibitors during iron‑rich meals:

- Drink tea/coffee after meals.

- Space calcium supplements away from iron meals.

- Employ food preparation techniques that lower phytate content:

- Soak beans overnight, discard soaking water, then cook.

- Use sourdough fermentation for whole‑grain breads.

- Consider fortified foods (e.g., iron‑fortified cereals or plant milks) especially in vegetarian or vegan diets.

Dietary Strategies to Lower High TSAT

Excessive TSAT (> 45 %) signals potential iron overload and warrants immediate medical evaluation. Dietary measures can complement therapeutic phlebotomy or chelation:

- Limit heme iron intake: Reduce red meat consumption to ≤ 2 servings/week.

- Avoid iron‑fortified products unless prescribed.

- Increase intake of natural iron chelators:

- Polyphenol‑rich foods (green tea, cocoa, berries) – consume between meals.

- Calcium‑rich foods (dairy, fortified plant milks) – can modestly inhibit iron absorption.

- Alcohol moderation: Excess alcohol increases intestinal iron absorption and hepatic iron deposition.

Important: Dietary restriction alone cannot normalize TSAT in hereditary hemochromatosis; therapeutic phlebotomy remains the cornerstone.

Integrating TSAT Into a Holistic Anemia Work‑up

- Initial labs: CBC, serum ferritin, serum iron, TIBC, TSAT, C‑reactive protein (CRP).

- Interpretation matrix:

| Ferritin | TSAT | CRP | Likely Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (< 30 µg/L) | Low (< 15 %) | Normal | Iron‑deficiency anemia |

| Normal/High | Low | Elevated | Anemia of chronic disease |

| High (> 300 µg/L) | High (> 45 %) | Normal/Low | Iron overload (hemochromatosis) |

- Follow‑up: Repeat TSAT after 1‑2 months of any dietary or therapeutic change to gauge response.

Actionable Checklist for Patients

- Get tested: Fasted blood draw for serum iron, TIBC, and TSAT every 3–6 months if you have known iron issues.

- Track diet: Use a food diary for 1 week, noting iron‑rich foods, vitamin C sources, and inhibitors.

- Optimize meals: Pair non‑heme iron foods with citrus or bell peppers; avoid tea/coffee with meals.

- Supplement wisely: Start low, take with vitamin C, separate from calcium, monitor side effects.

- Review meds: Proton‑pump inhibitors, antacids, and certain antibiotics can impair iron absorption—discuss alternatives with your clinician.

- Lifestyle: Regular aerobic exercise improves erythropoiesis and may modestly enhance iron utilization.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of abnormal Transferrin Saturation levels?

The most frequent cause of a low TSAT is iron‑deficiency anemia, usually due to chronic blood loss (menstruation, gastrointestinal bleeding) or inadequate dietary iron. A high TSAT most commonly results from hereditary hemochromatosis, a genetic disorder that leads to excessive intestinal iron absorption, or from repeated blood transfusions in conditions such as thalassemia. Inflammatory states can also produce a low TSAT by raising hepcidin, which blocks iron release from stores.

How often should I get my Transferrin Saturation tested?

For individuals without known iron disorders, a routine TSAT is not required. If you have iron‑deficiency, hemochromatosis, or are undergoing iron therapy, testing every 3–6 months is advisable to assess response and avoid oversaturation. Pregnant women should have TSAT checked each trimester if they are at risk for deficiency. Always follow your clinician’s personalized schedule based on clinical status and treatment plan.

Can lifestyle changes improve my Transferrin Saturation levels?

Yes. Dietary modifications—such as increasing heme iron intake, pairing non‑heme iron foods with vitamin C, and reducing intake of iron absorption inhibitors (tea, coffee, calcium during meals)—can raise a low TSAT. Conversely, limiting red meat, avoiding iron‑fortified foods, and incorporating polyphenol‑rich beverages can help lower an elevated TSAT. Additionally, addressing underlying inflammation (through weight management, smoking cessation, and treating chronic infections) can normalize hepcidin levels and improve iron utilization. Regular physical activity also supports healthy erythropoiesis, indirectly influencing TSAT.

Take charge of your iron health by understanding the numbers, nourishing your body with the right foods, and partnering with your healthcare provider for targeted testing and treatment.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Always consult a healthcare professional.