Treatment Options for Abnormal Transferrin Levels

Reference Ranges for Transferrin Saturation

| Population | Normal Range | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Men | 20‑45 | % | Upper limit may be lower in iron‑overload disorders |

| Adult Women (premenopausal) | 15‑35 | % | Often reduced by menstrual blood loss |

| Adult Women (postmenopausal) | 20‑45 | % | Similar to men after menopause |

| Children (6‑12 y) | 15‑35 | % | Age‑dependent; puberty shifts toward adult values |

| Adolescents (13‑18 y) | 18‑40 | % | Rapid changes during growth spurts |

| Pregnant Women (1st trimester) | 15‑35 | % | Physiologic dilution; 2nd‑3rd trimester may fall lower |

| Elderly (>65 y) | 20‑45 | % | May be modestly reduced by chronic disease |

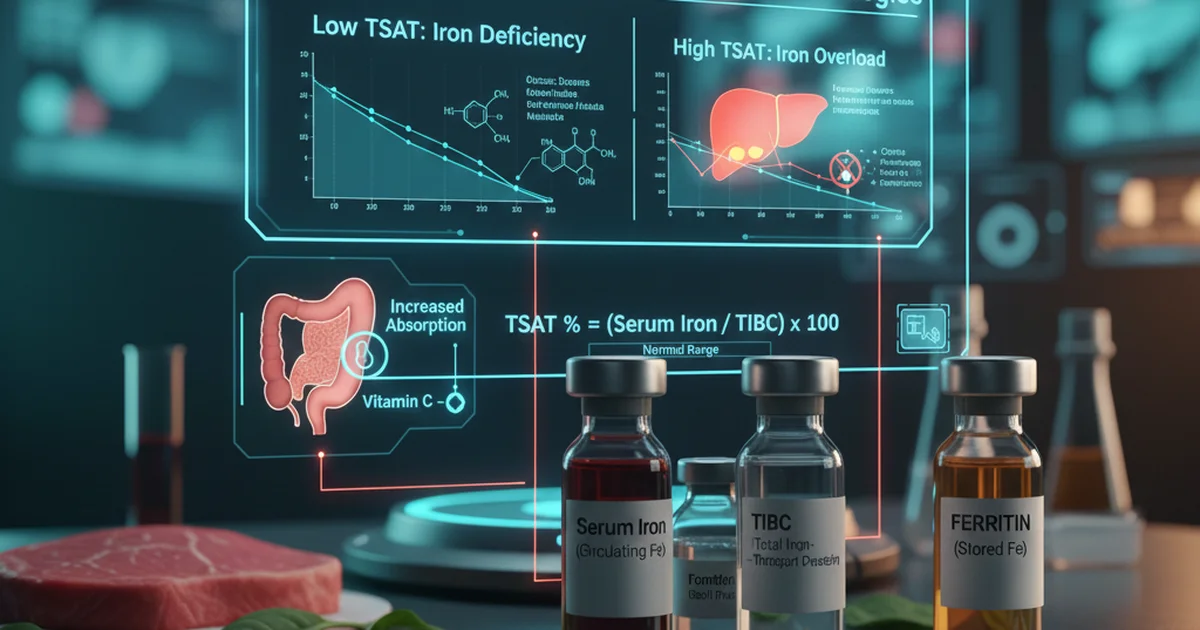

Transferrin saturation (TSAT) is calculated as (Serum Iron ÷ Total Iron‑Binding Capacity) × 100. Values outside the ranges above signal either iron deficiency (low TSAT) or iron overload (high TSAT).

Introduction

Transferrin is the primary iron‑transport protein in plasma. Its saturation reflects the proportion of binding sites occupied by iron and is a rapid, sensitive indicator of whole‑body iron status. Abnormal TSAT—whether too low or too high—can precipitate a cascade of clinical problems ranging from anemia and fatigue to organ damage due to iron toxicity. This article reviews the physiology of transferrin, explores the dietary and supplemental strategies that influence TSAT, and outlines evidence‑based treatment options for correcting abnormal values.

Physiology of Transferrin and Its Saturation

How Transferrin Works

- Synthesis: Produced mainly by hepatocytes; each molecule has two high‑affinity iron‑binding sites.

- Transport: Carries ferric (Fe³⁺) iron from intestinal absorption sites and macrophage recycling to the bone marrow, liver, and spleen.

- Regulation: Hepcidin, a liver‑derived peptide hormone, controls iron release from enterocytes and macrophages; hepcidin levels rise when TSAT is high, reducing further iron absorption.

What Transferrin Saturation Indicates

- Low TSAT (< 15 %) → Insufficient iron for erythropoiesis; often precedes a fall in hemoglobin.

- High TSAT (> 45 %) → Excess iron circulating unbound, increasing the risk of non‑transferrin‑bound iron (NTBI) that can catalyze oxidative damage.

Causes of Abnormal Transferrin Saturation

Low TSAT

| Category | Typical Mechanisms |

|---|---|

| Dietary deficiency | Inadequate intake of heme or non‑heme iron; diets high in phytates, polyphenols, or calcium |

| Chronic blood loss | Menstruation, gastrointestinal bleeding, frequent donation |

| Malabsorption | Celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, bariatric surgery |

| Inflammation | Acute‑phase response raises ferritin and lowers serum iron, lowering TSAT |

| Genetic disorders | Iron‑refractory iron deficiency anemia (IRIDA) caused by TMPRSS6 mutations |

High TSAT

| Category | Typical Mechanisms |

|---|---|

| Hereditary hemochromatosis | Mutations (HFE, HJV, TFR2) impair hepcidin regulation, causing relentless iron absorption |

| Repeated transfusions | Secondary iron overload in thalassemia, sickle cell disease |

| Excessive dietary iron | Overconsumption of iron‑fortified foods or supplements |

| Liver disease | Impaired synthesis of transferrin reduces binding capacity, raising saturation |

Dietary Sources that Influence TSAT

Iron‑Rich Foods

| Food Type | Heme Iron (mg/100 g) | Non‑Heme Iron (mg/100 g) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beef liver | 6.5 | 0.5 | Extremely bioavailable; consume in moderation |

| Red meat (beef) | 2.6 | 0.4 | Good source of heme iron |

| Chicken thigh (dark) | 1.5 | 0.3 | Moderate heme iron |

| Salmon (cooked) | 0.9 | 0.5 | Also provides omega‑3 fatty acids |

| Lentils (cooked) | 0 | 3.3 | High non‑heme iron; absorption enhanced with vitamin C |

| Spinach (cooked) | 0 | 3.6 | Contains oxalates that inhibit absorption; pair with citrus |

| Fortified breakfast cereal | 0 | 6‑12 | Often includes iron salts with high bioavailability |

| Pumpkin seeds | 0 | 3.0 | Good snack; also provides zinc and magnesium |

Enhancers of Iron Absorption

- Vitamin C (ascorbic acid): Reduces ferric to ferrous iron, dramatically increasing non‑heme iron uptake. One medium orange (~70 mg) can double absorption from a plant‑based meal.

- Animal protein (meat factor): Peptides from meat, fish, or poultry improve non‑heme iron uptake.

- Organic acids (citric, malic): Present in fruit juices; act similarly to vitamin C.

Inhibitors of Iron Absorption

- Phytates: Found in whole grains, legumes, nuts; bind iron and reduce bioavailability. Soaking, sprouting, or fermenting can lower phytate content.

- Polyphenols: Tea, coffee, red wine; tannins form insoluble complexes with iron. Avoid drinking these beverages with iron‑rich meals.

- Calcium: Dairy products and calcium supplements compete with iron for intestinal transport. Separate calcium intake by at least two hours from iron‑rich meals.

- Soy protein isolates: Contain phytates and polyphenols; may blunt iron absorption.

Bioavailability: Heme vs. Non‑Heme Iron

- Heme iron (from animal sources) is absorbed via a dedicated transporter and is 15‑35 % efficiently taken up, largely unaffected by dietary inhibitors.

- Non‑heme iron (plant sources, fortified foods) has a 2‑20 % absorption range, highly modifiable by enhancers and inhibitors.

- Practical implication: For individuals with low TSAT, incorporating even modest amounts of heme iron can raise saturation more quickly than relying solely on non‑heme sources. Vegetarians can achieve comparable results by pairing iron‑rich foods with vitamin C and minimizing inhibitors.

Supplementation Strategies

Oral Iron Preparations

| Form | Typical Dose (elemental Fe) | Absorption Rate | Common Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ferrous sulfate | 325 mg (≈ 65 mg elemental) | 10‑15 % | Nausea, constipation, dark stools |

| Ferrous gluconate | 240 mg (≈ 35 mg elemental) | 10‑12 % | Milder GI upset |

| Ferrous fumarate | 300 mg (≈ 106 mg elemental) | 12‑15 % | Similar to sulfate |

| Carbonyl iron | 100 mg (≈ 100 mg elemental) | 20‑25 % | Lower GI irritation |

| Polysaccharide‑iron complex | 100 mg (≈ 100 mg elemental) | 15‑20 % | Well tolerated, slower release |

Key points for optimal oral therapy

- Take on an empty stomach (30 min before meals) to maximize absorption, unless GI intolerance occurs.

- Use a vitamin C‑rich beverage (orange juice) to boost uptake.

- Split the total daily dose into 2‑3 administrations to reduce saturation of transporters and limit side effects.

- Re‑evaluate TSAT after 4‑6 weeks; adjust dose based on response.

Intravenous Iron

Reserved for:

- Severe iron deficiency unresponsive to oral therapy (e.g., malabsorption, inflammatory bowel disease).

- Chronic kidney disease patients on dialysis.

- Pre‑operative optimization when rapid repletion is needed.

Common IV preparations: ferric carboxymaltose, iron sucrose, and ferumoxytol. They deliver large elemental iron loads (up to 1 g) in a single or few sessions, raising TSAT within days. Safety note: Monitor for hypersensitivity reactions; ensure adequate resuscitation equipment is available.

Iron Chelation (for High TSAT)

When TSAT > 45 % due to iron overload, the goal is to reduce circulating iron and prevent organ damage.

- Deferasirox (oral): Binds iron and facilitates urinary excretion; dose titrated to serum ferritin and TSAT trends.

- Deferoxamine (parenteral): Requires subcutaneous infusion; used when rapid removal is needed.

- Deferiprone (oral): Effective for cardiac iron removal; used in combination therapy for severe cases.

Chelation is not indicated for transiently elevated TSAT from short‑term excess intake; dietary modification is the first line.

Monitoring and Treatment Algorithms

- Baseline assessment – Complete blood count, serum iron, TIBC, ferritin, TSAT, and inflammatory markers (CRP).

- Identify etiology – Review diet, menstrual history, GI symptoms, family history of hemochromatosis, and medication list (e.g., proton pump inhibitors).

- Low TSAT pathway

- Mild deficiency (TSAT 10‑15 %): Optimize diet with heme sources + vitamin C; consider low‑dose oral iron (30‑60 mg elemental).

- Moderate deficiency (TSAT 5‑10 %): Start standard oral iron (100‑200 mg elemental/day) for 8‑12 weeks; re‑check TSAT.

- Severe deficiency (TSAT < 5 % or symptomatic anemia): IV iron or high‑dose oral iron; treat underlying cause (e.g., GI bleed).

- High TSAT pathway

- Transient elevation (dietary excess): Counsel on reducing iron‑fortified foods and supplements; re‑measure in 4 weeks.

- Persistent elevation (≥ 45 % on two separate tests): Evaluate for hereditary hemochromatosis (genetic testing) and organ involvement; initiate phlebotomy or chelation as indicated.

Actionable advice: Keep a food and supplement diary for at least two weeks before testing; this helps clinicians differentiate dietary impact from pathologic iron disorders.

Lifestyle and Dietary Recommendations

For Low TSAT

- Eat a “iron‑boosting” meal at least once daily: grilled steak (3 oz) + roasted bell peppers + a side of quinoa, followed by a glass of orange juice.

- Avoid tea/coffee within 1 hour of iron‑rich meals.

- Incorporate fermented grains (sourdough bread) to reduce phytate content.

- Consider cooking in cast‑iron cookware; up to 5 mg of iron can leach into acidic foods.

- Limit calcium supplements during iron therapy; separate by 2 hours.

For High TSAT

- Reduce intake of red meat and iron‑fortified cereals; switch to poultry, fish, and plant proteins.

- Avoid unnecessary supplemental iron unless prescribed.

- Increase consumption of natural iron chelators such as green tea (moderate amounts) and foods high in polyphenols, which can modestly lower iron absorption.

- Maintain regular phlebotomy schedule (if indicated) – typically 500 mL whole blood every 1‑2 weeks until TSAT falls below 30 %.

Special Populations

| Population | Typical Issue | Tailored Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnant women | Physiologic dilution, increased iron demand | Begin prenatal iron (30‑60 mg elemental) with vitamin C; monitor TSAT each trimester. |

| Athletes | Exercise‑induced inflammation may mask iron status | Use TSAT together with ferritin and soluble transferrin receptor; avoid high‑dose iron unless deficiency confirmed. |

| Elderly | Co‑existing chronic disease, reduced gastric acid | Consider low‑dose oral iron with a proton pump inhibitor holiday; IV iron if malabsorption suspected. |

| Vegetarians/Vegans | Reliance on non‑heme iron | Emphasize vitamin C pairing, soaking/fermentation of legumes, and occasional heme‑iron (e.g., eggs, dairy) if tolerated. |

| Patients with chronic kidney disease | Anemia of chronic disease plus iron deficiency | Use IV iron to bypass hepcidin‑mediated blockade; monitor TSAT and ferritin closely. |

Practical Action Plan for Patients

- Schedule a blood test that includes serum iron, TIBC, ferritin, and TSAT.

- Track dietary intake for 14 days, noting iron‑rich foods, vitamin C sources, and inhibitors.

- Consult a healthcare professional to interpret results and rule out genetic or inflammatory causes.

- Implement dietary changes based on the “iron‑boosting” or “iron‑moderating” guidelines above.

- Start supplementation only after confirming deficiency or after a physician’s recommendation for overload management.

- Re‑evaluate TSAT after 4–6 weeks of intervention; adjust plan accordingly.

Conclusion

Transferrin saturation is a pivotal, readily measurable marker of iron balance. Abnormal TSAT—whether low or high—signals the need for targeted dietary, supplemental, or therapeutic interventions. By understanding the sources of iron, the factors that modulate its absorption, and the appropriate use of oral or intravenous preparations, clinicians and patients can restore optimal TSAT, improve hematologic health, and prevent the long‑term complications of iron dysregulation. Consistent monitoring, personalized nutrition, and evidence‑based supplementation remain the cornerstones of effective treatment.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of abnormal Transferrin Saturation levels?

The most frequent cause of low TSAT is inadequate dietary iron combined with chronic blood loss (e.g., heavy menstrual periods or gastrointestinal bleeding). For high TSAT, hereditary hemochromatosis—an inherited defect in hepcidin regulation—accounts for the majority of cases, especially in individuals of Northern European descent.

How often should I get my Transferrin Saturation tested?

- If you have known iron deficiency or are on iron therapy: Re‑check TSAT every 4‑6 weeks until it reaches the target range, then every 3–6 months.

- If you have iron overload or are undergoing phlebotomy/chelation: Test TSAT every 1‑2 months to guide treatment frequency.

- Routine screening for the general population: Not required unless risk factors (family history, chronic disease) are present.

Can lifestyle changes improve my Transferrin Saturation levels?

Absolutely. Increasing intake of heme iron, pairing non‑heme iron foods with vitamin C, and minimizing inhibitors such as tea, coffee, and high calcium meals can raise low TSAT within weeks. Conversely, reducing red meat consumption, avoiding unnecessary iron supplements, and incorporating natural iron‑binding foods can help lower high TSAT. Consistency in these dietary habits, together with periodic monitoring, is essential for sustained improvement.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Always consult a healthcare professional.