Understanding Your High Monocyte Count (Monocytosis)

Direct answer: High monocytes, a condition called monocytosis, means you have an elevated level of a specific type of white blood cell. This is most often a sign that your body is fighting a chronic infection, inflammation, or an autoimmune disease. While often temporary, persistently high levels can sometimes indicate more serious conditions, including certain blood disorders or cancers. Your doctor will use this result along with other tests to determine the underlying cause and appropriate next steps for your health.

TL;DR High monocyte levels, known as monocytosis, are a common finding on a complete blood count (CBC) test. These specialized white blood cells are a key part of your immune system, responsible for fighting off certain infections, removing dead cells, and supporting tissue repair. When their numbers are elevated, it's a signal that your body is actively responding to a health challenge. The most frequent causes are chronic infections and persistent inflammation, but the specific reason requires further investigation by a healthcare professional.

- Monocytes are a type of white blood cell that helps fight infection and inflammation.

- High levels (monocytosis) are typically defined as a count above 800/μL or >10% of your total white blood cells.

- Common causes include chronic infections (like tuberculosis or fungal infections), autoimmune diseases (like lupus or rheumatoid arthritis), and chronic inflammatory conditions.

- Monocytosis is usually a sign of your body's immune response, not a disease in itself. The goal is to find and treat the root cause.

- Less common but more serious causes can include certain types of leukemia, such as chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML).

- Your doctor will interpret your monocyte count in the context of your other blood test results, symptoms, and medical history to make a diagnosis.

Want the full explanation? Keep reading ↓

High Monocytes (Monocytosis): Chronic Infection & Inflammation

A high monocyte count on your blood test results, a condition known as monocytosis, can be unsettling. While it's rarely a standalone issue, it serves as a valuable clue for your healthcare provider, often pointing toward an underlying process of chronic infection or inflammation in the body. Understanding what monocytes are and why they might be elevated is the first step in addressing the root cause.

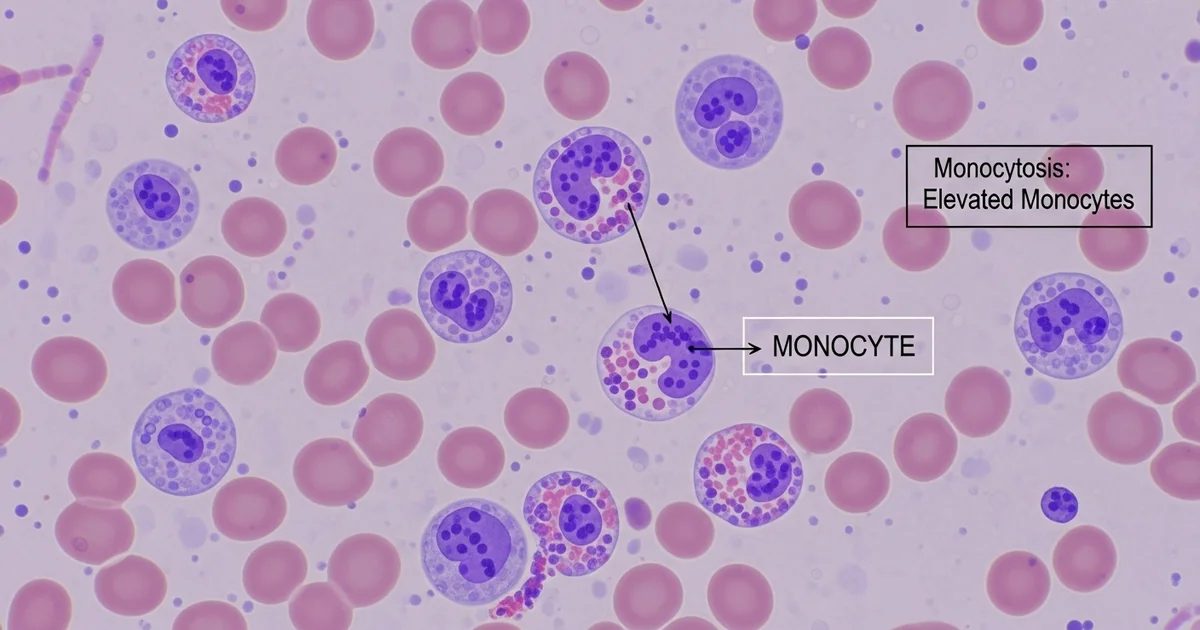

Monocytes are a type of white blood cell, manufactured in the bone marrow. They are the largest of the white blood cells and act as the immune system's "cleanup crew." After circulating in the bloodstream for a few days, they migrate into tissues, where they mature into macrophages or dendritic cells, ready to tackle a variety of threats. To learn more about their fundamental role, you can explore this overview of the [monocytes blood test and the body's cleanup crew].

When your body faces a persistent challenge—like a stubborn infection, ongoing inflammation from an autoimmune disease, or even certain types of cancer—it ramps up the production of these powerful cells. The resulting elevation in your complete blood count (CBC) is monocytosis.

Seeing High Monocytes on Your Report? Here's the Clinical Definition

When you review your lab report, you'll see monocytes reported in two ways: a relative percentage (%) and an absolute count. While the percentage is useful, clinicians place far more importance on the absolute monocyte count (AMC). This number represents the actual quantity of monocytes in a specific volume of blood and provides a much more accurate picture of what's happening.

Monocytosis is clinically defined as an absolute monocyte count that exceeds the upper limit of the normal reference range. For most adults, this means a count greater than 1,000 cells per microliter (cells/mcL). However, what's considered "normal" can vary based on age and the specific laboratory performing the test.

Monocyte Reference Ranges: Absolute Count

The table below outlines typical reference ranges for absolute monocyte counts. It is crucial to compare your results to the specific range provided by the lab that processed your blood sample. For a deeper dive into these values, it's helpful to understand the details of a [normal monocyte range and absolute count].

| Population | Absolute Count Range | Units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | 200 - 1,000 | cells/mcL | Monocytosis is typically >1,000 cells/mcL. |

| Newborns (0-1 mo) | 100 - 2,100 | cells/mcL | A higher range is normal and expected at this age. |

| Children (1-4 yrs) | 200 - 1,100 | cells/mcL | Varies slightly by age; count gradually decreases to adult levels. |

| During Pregnancy | 300 - 1,200 | cells/mcL | A mild, temporary increase is common and usually not a concern. |

Important Note: A result that is slightly outside this range may not be clinically significant. Your doctor will interpret your monocyte count in the context of your overall health, other blood test results, and any symptoms you may be experiencing.

Uncovering the Root Causes: Why Are Your Monocytes Elevated?

Monocytosis is a sign, not a disease. Think of it as a smoke signal indicating a fire somewhere in the body. The primary role of a healthcare provider is to find the source of that smoke. The causes of high monocytes are broad but can be grouped into several key categories.

Chronic Infections: The Persistent Invaders

Monocytes are experts at fighting infections that other white blood cells struggle to clear quickly. When an infection becomes chronic or subacute, the body continuously produces monocytes to contain the threat.

Common infectious causes include:

- Tuberculosis (TB): Monocytosis is a classic finding in this persistent bacterial lung infection.

- Subacute Bacterial Endocarditis: An infection of the heart valves, often leading to a sustained immune response.

- Viral Infections (during recovery): While some viruses cause an initial drop in white blood cells, the recovery phase often involves a spike in monocytes as the body cleans up cellular debris. Epstein-Barr virus (the cause of mononucleosis) is a prime example.

- Fungal Infections: Systemic fungal diseases like histoplasmosis or blastomycosis can trigger a strong monocytic response.

- Syphilis and Brucellosis: These less common bacterial infections are also known to cause monocytosis.

Autoimmune & Inflammatory Disorders: When the Body Attacks Itself

In autoimmune and autoinflammatory conditions, the immune system mistakenly attacks the body's own healthy tissues. Monocytes and the macrophages they become are key players in this process, contributing to chronic inflammation and tissue damage.

Monocytosis is frequently observed in:

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Both Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis are associated with elevated monocytes, which correlate with disease activity.

- Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA): These immune cells infiltrate the joints, causing the inflammation and pain characteristic of RA.

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE): Monocytosis is a common finding in lupus, reflecting widespread systemic inflammation.

- Sarcoidosis: A disease characterized by the formation of inflammatory cell clusters (granulomas) in organs like the lungs and lymph nodes. Monocytosis is a hallmark of this condition.

- Vasculitis: Inflammation of the blood vessels can also lead to an increased monocyte count.

Blood Disorders & Cancers: A Sign of Deeper Issues

In some cases, monocytosis originates from a problem within the bone marrow itself, where blood cells are made. This is one of the most serious potential causes and requires prompt evaluation by a hematologist.

It is crucial to understand that while cancer is a possible cause, most cases of monocytosis are due to infection or inflammation.

Hematologic conditions associated with high monocytes include:

- Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukemia (CMML): This is a rare type of blood cancer where persistent, unexplained monocytosis is a defining characteristic. It primarily affects older adults.

- Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML): Certain subtypes of this aggressive leukemia, particularly AML-M4 and AML-M5, are characterized by a high number of monocytic cells.

- Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS): A group of bone marrow disorders where the body produces abnormal, non-functional blood cells. Some forms of MDS can evolve into leukemia.

- Hodgkin's and Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma: These cancers of the lymphatic system can sometimes trigger a reactive monocytosis.

Other Potential Causes of Monocytosis

Beyond the main categories, several other situations can lead to a temporary or sustained increase in monocytes.

| Cause Category | Specific Examples | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Post-Surgery | Major operations (e.g., cardiac, abdominal) | Inflammation and tissue repair after surgery stimulate monocyte production to clean up damaged cells. |

| Splenectomy | Surgical removal of the spleen | The spleen normally filters and stores a portion of monocytes; its removal can lead to higher circulating levels. |

| Medications | Corticosteroids, certain growth factors | Some drugs can influence bone marrow production, leading to a temporary rise in monocytes. |

| Recovery Phase | Post-chemotherapy, recovery from neutropenia | As the bone marrow recovers from suppression, it can "overshoot," causing a temporary spike in monocytes. |

Feeling Worried? Here’s Your Action Plan for High Monocytes

Receiving a lab result showing high monocytes can be stressful, but it's important to approach it systematically. A single elevated reading is just one piece of the puzzle. Here’s what you and your doctor will likely do next.

Step 1: Confirm and Contextualize the Result

The first step is to ensure the result is not a fluke and to understand its context.

- Repeat the Test: Your doctor may want to repeat the CBC in a few weeks or months to see if the monocytosis is persistent or transient. A temporary elevation that resolves on its own is less concerning.

- Review Your History: Your doctor will conduct a thorough review of your medical history, including any recent illnesses, surgeries, new medications, and family history.

- Perform a Physical Exam: A comprehensive physical exam can reveal important clues, such as swollen lymph nodes, an enlarged spleen (splenomegaly), fever, or signs of joint inflammation.

Step 2: Look for Clues in Other Lab Tests

Your monocyte count is part of a larger panel of tests. Your doctor will carefully analyze the entire CBC and may order additional blood work.

What to Look For in Your CBC:

- Other White Blood Cells: Are neutrophils (infection-fighting cells) or lymphocytes (immune memory cells) also high or low?

- Red Blood Cells and Hemoglobin: Is there evidence of anemia (low red blood cells), which is common in chronic disease?

- Platelets: Are platelets, which are involved in clotting, abnormally high or low?

Additional Blood Tests May Include:

- Peripheral Blood Smear: A specialist examines your blood under a microscope to look at the size, shape, and maturity of your monocytes and other blood cells. This is critical for ruling out blood cancers like leukemia.

- Inflammatory Markers: Tests like C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) can confirm the presence of systemic inflammation.

- Specific Serologies: If an infection is suspected, your doctor will order tests for specific viruses, bacteria, or fungi.

- Autoimmune Panel: Tests for antibodies like ANA (antinuclear antibody) or RF (rheumatoid factor) if an autoimmune condition is suspected.

Step 3: Advanced Diagnostic Workup (If Needed)

If the initial workup does not reveal a clear cause, or if there is a high suspicion of a hematologic disorder, more advanced testing is required.

- Bone Marrow Biopsy: This is the definitive test for diagnosing conditions like leukemia, MDS, and CMML. A hematologist takes a small sample of bone marrow (usually from the hip bone) for detailed analysis.

- Imaging Studies: X-rays, CT scans, or ultrasounds may be used to look for signs of infection, inflammation, or tumors in the lungs, abdomen, or other parts of the body.

By following this structured approach, your healthcare team can effectively narrow down the potential causes of your monocytosis and determine the appropriate course of action.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most common cause of abnormal Monocytes levels?

The most common causes of a mildly elevated monocyte count are transient viral infections and the subsequent recovery phase. As the body fights off common viruses and cleans up the resulting cellular debris, it's normal to see a temporary spike in monocytes that resolves on its own. The second most common category includes chronic inflammatory and autoimmune conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or rheumatoid arthritis, where monocytosis reflects ongoing disease activity. While serious conditions like leukemia are a possible cause, they are significantly less common.

How often should I get my Monocytes tested?

For a healthy individual with no symptoms, monocyte levels are checked as part of a routine complete blood count (CBC) during a standard physical, which may be annually or every few years. There is no need for more frequent screening. If you have been diagnosed with a condition known to cause monocytosis (like an autoimmune disease or a hematologic disorder), your doctor will establish a specific monitoring schedule based on your diagnosis, treatment plan, and overall stability. If an initial test shows high monocytes, your doctor will likely recommend a follow-up test in a few weeks to months to see if the elevation is persistent.

Can lifestyle changes improve my Monocytes levels?

If your monocytosis is caused by an underlying chronic disease, lifestyle changes alone will not "fix" the count. The primary goal is to treat the root cause with the help of your doctor. However, adopting a healthy, anti-inflammatory lifestyle can support your overall immune function and may help manage the underlying condition causing the inflammation. This includes eating a balanced diet rich in fruits and vegetables, engaging in regular moderate exercise, managing stress, getting adequate sleep, and avoiding smoking. These habits help create a healthier internal environment but are complementary to, not a replacement for, medical treatment.

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. Always consult a healthcare professional.